In America, the heavily spiced condiment has been diluted, distorted, and sold en masse. Mansour Arem’s setting the record straight.

Have you ever eaten something that smashed all your previous conceptions to smithereens? Mansour Arem’s harissa can do that to you.

My first bite, raw from a jar that my buddy Garrett Oliver—Arem’s former boss at Brooklyn Brewery—hand-delivered to my door (so great was his zeal for this harissa), hit me like Proust’s madeleine. It was a taste that unlocked a memory. As I rolled the plush paste around with my tongue, the flavors of bitter olive oil and ruddy coriander revealed themselves. Then a jolt of fruit—yes, chiles are technically fruits, but are there blueberries in here?—then a slow, smoldering heat that tickled my gums and beckoned another spoonful.

I’m an experienced cook and supposedly well-cultured food writer. I’ve eaten lots of harissa before, straight with pita and cooked into innumerable dishes. I’ve even written articles about how to cook with it. Yet here was something that electrified me like no harissa I’d tried before. As I licked the remnants of the peppery condiment off my spoon, I started to worry. If this is homemade harissa, what have I been eating all this time? Do I know anything about harissa at all?

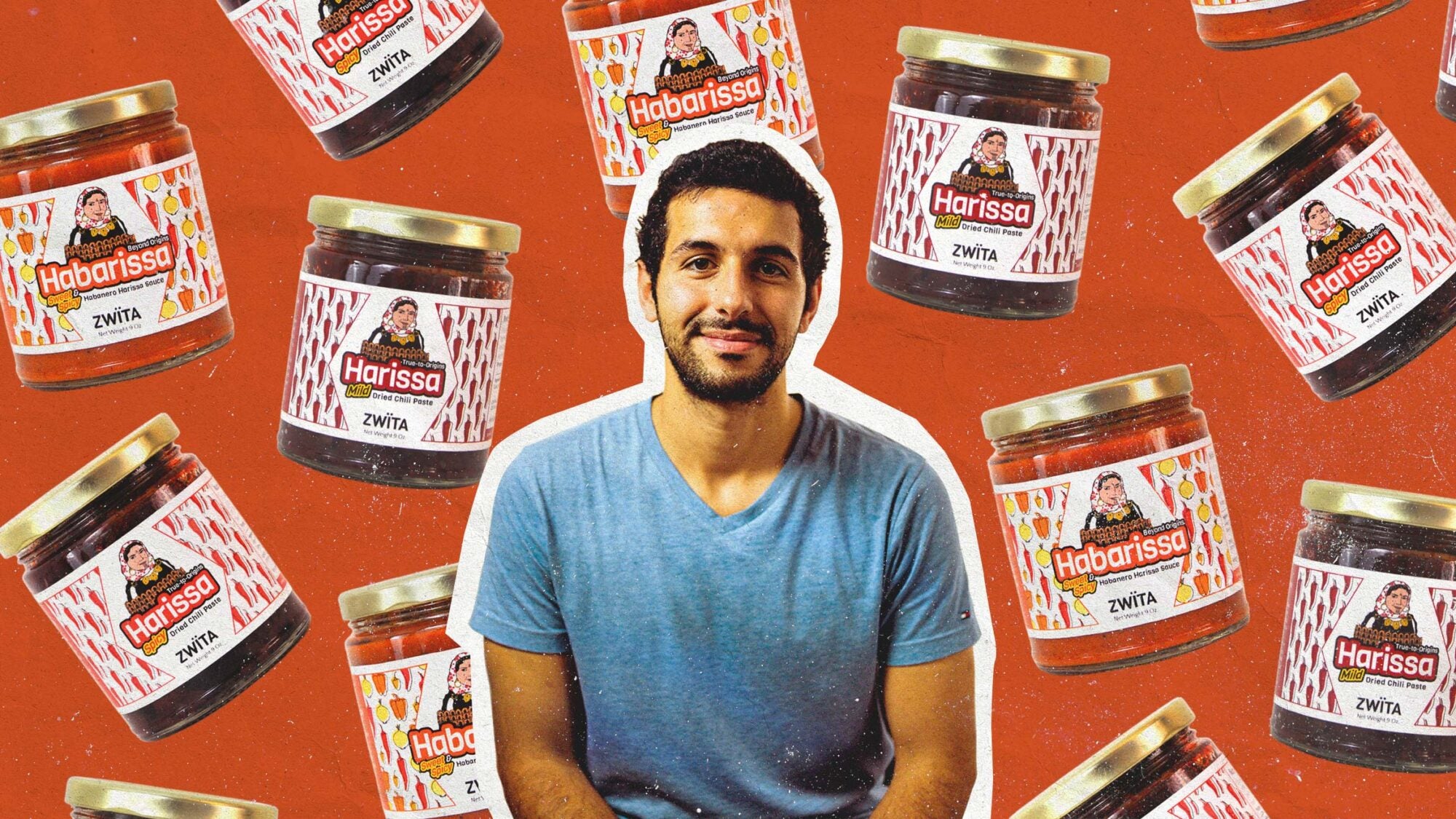

For Arem, a 26-year-old food and fermentation scientist in Houston, Texas, whose new harissa company, Zwïta Foods, will launch later this year, harissa is as much a ritual as a recipe. When Arem was only five, his father, who immigrated to the United States in the 1970s, picked up the family to move back to his native Tunisia. “He was afraid my brother and I would lose touch with our roots,” Arem recalls. “He wanted to make sure we were Tunisian.” He hopped between Tunisia and the United States throughout his childhood. And when you’re in Tunisia, you eat harissa. A smear of the paste sliced with olive oil, served with olives, almonds, tinned tuna, and pita, was a common snack in his family’s kitchen.

As I licked the remnants of the peppery condiment off my spoon, I started to worry. If this is homemade harissa, what have I been eating all this time?

“More people are buying premade harissa in the souks,” he goes on, “but quite a few still make it at home. My aunt does, my grandmother does. My mom doesn’t trust the premade souk harissas, as she’s sure many vendors cut corners with their ingredients.”

So does Arem, who started Zwïta with his brother as a side project during the off-hours of his day job, managing fermentation and production at a brewery. First, he cleans, stems, and seeds dried guajillo chiles, then he rehydrates them until they flop in his hands like wet seaweed. The longer dried chiles sit around, the more their flavors dissipate, leaving behind a dull, faded image of the peppers they used to be. The Peruvian-grown chiles Arem uses are still pliant before their spa treatment—a sign their fruity vitality is still intact. Eventually, he intends to import Tunisian peppers for his harissa, but for now, his chief concern is the freshness of his chiles, and these hit his mark nicely.

When his mother makes harissa at home, she pulverizes the chiles with a meat grinder, the best way to smash and squeeze the flavor out of the peppers, rather than merely shredding them to ribbons. Arem uses a similar machine on an industrial scale, mashing the chiles with raw garlic and salt into a thick paste that’s then heated in 60-gallon kettles in a process that takes several hours. Right before the paste is ready to be filled into jars, he loosens it with peppery olive oil and the traditional coriander and caraway, to maintain as much of their pungent spice as possible.

It took me a while to calibrate my cooking to his harissa; it’s subtler than most of the mass-market and specialty brands I’ve tried, like Harissa Du Cap Bon and Bebert’s—not the sort of thing to absentmindedly stir into a wan pot of pasta sauce that needs punching up. “A lot of people think harissa is about spiciness,” he says, “but it’s really about the quality of the chiles, the olive oil, the spices. The traditional harissa is valuable in two senses: the time and labor required to make it, and the value that you’re getting, the amount of chiles and flavor instead of water.”

The calibration was, frankly, uncomfortable. It required me to put aside my ego, my personal sense of what something should taste like, and really pay attention to what was in front of me. This rich yet only mildly spicy paste was a far cry from what the Washington Post in 2017 christened “the new sriracha.” (That paper was far from the only one to do so.) But when smeared on warm bread and dipped into olive oil, blam, there was that madeleine moment again, making me homesick for a place I’ve never been. Though Arem doesn’t want to be constrained by traditional harissa formats, he’s also working on a sweet and spicy bottled hot sauce that uses the same harissa base but punches up the heat with habaneros.

“Harissa is being appropriated by non-Tunisian business owners who purposefully dilute the product’s history to make it more marketable and approachable to consumers who don’t know any better.”

The ascension of harissa in cookbooks and food writing (and those who follow it) over the past five years is a familiar story. Yotam Ottolenghi calls it one of his essential pantry staples, and suddenly, harissa is the new hotness, just like turmeric, chile crisp, and açai. It doesn’t take long for the food to be uncoupled from its origins, diluted and discombobulated for the sake of mass appeal and consumption. As a restaurant industry publication puts it in insidiously inchoate corporate babble, “Harissa provides the opportunity for operators to embrace a trendy, global ingredient and appeal to heat lovers everywhere.”

“It doesn’t matter if the food is true to its origins or not,” Arem laments. “If I were to take shortcuts and tweak this product in a more profitable way, but you don’t know anything about it, and I’m using spices that you’re not used to consuming, you’re going to think it’s amazing and special, even if it’s not actually good or authentic or valuable.” There’s an inflection point, in Arem’s view, where making an ingredient “accessible” to a wider audience does more harm than good. “There’s a quote-unquote openness to other food cultures in the United States, to seek out other flavors, but those flavors also must be health conscious, they must fit into American diets, and they must serve a practical use,” he laments. American commercial acceptance comes at a price, and Arem considers himself fortunate to have the choice as to whether and how much he’s willing to pay for it.

Arem sees Zwïta as an opportunity to adjust this trajectory, and to educate people about harissa’s Tunisian roots. “There aren’t many Tunisians representing their own cuisine,” he says, “and now harissa isn’t seen as a Tunisian thing. It’s vaguely Middle Eastern or North African, which is totally false. Harissa is being appropriated by non-Tunisian business owners who purposefully dilute the product’s history to make it more marketable and approachable to consumers who don’t know any better. It’s like me trying to sell sriracha as an ‘Asian sauce.’ It’s profit-seeking at the expense of my culinary heritage. I cannot accept that.”