Famous for her cookies and Goldfish crackers, Rudkin’s influence extends beyond packaged foods. Long before second-wave feminism, she encouraged women to take their place in the American workforce.

Revisiting a love from your youth can be a dicey affair. You’ve changed, and so has the world. It’s rare that a soft feeling can survive the hardening and the grind of time rolling forward, crushing things-that-were to powdery bits. Some were the product of a particular time and place; many are better carried forth as memories, not practices, things worth holding onto only in their haziness.

Maybe that’s why I was surprised when I had my last Pepperidge Farm cookie. It was a Brussels, two crispy blond cookie rounds sandwiching a layer of smooth dark chocolate, from the brand’s “Distinctive Cookies” line. In the intervening years since my last, I’ve had all sorts of quality baked goods made with good ingredients, like Valrhona chocolate or rye flour for a distinctive chew, turned out at famous French bakeries or young and wild Brooklyn ones. When you bite down on the air-pocked cookies, they crunch and snap, giving way to chocolate. The Brussels was even better than I remembered.

Perhaps that is because the Brussels lives up to the promise of its line—“Distinctive”—as does the company itself. Pepperidge Farm makes an assortment of products whose quality is unreliant on nostalgia, like the top-loading hot dog buns treasured by New England chefs or the bagged stuffing still favored by Bon Appétit editors. It is the company that introduced those iconic Goldfish crackers still housed in plastic cups and tucked into strollers, and frozen puff pastry, called “a glamorous new product to America” in 1958. This is all thanks to Pepperidge Farm’s founder: one Margaret Rudkin, who, like her cookies, was exceptionally distinctive.

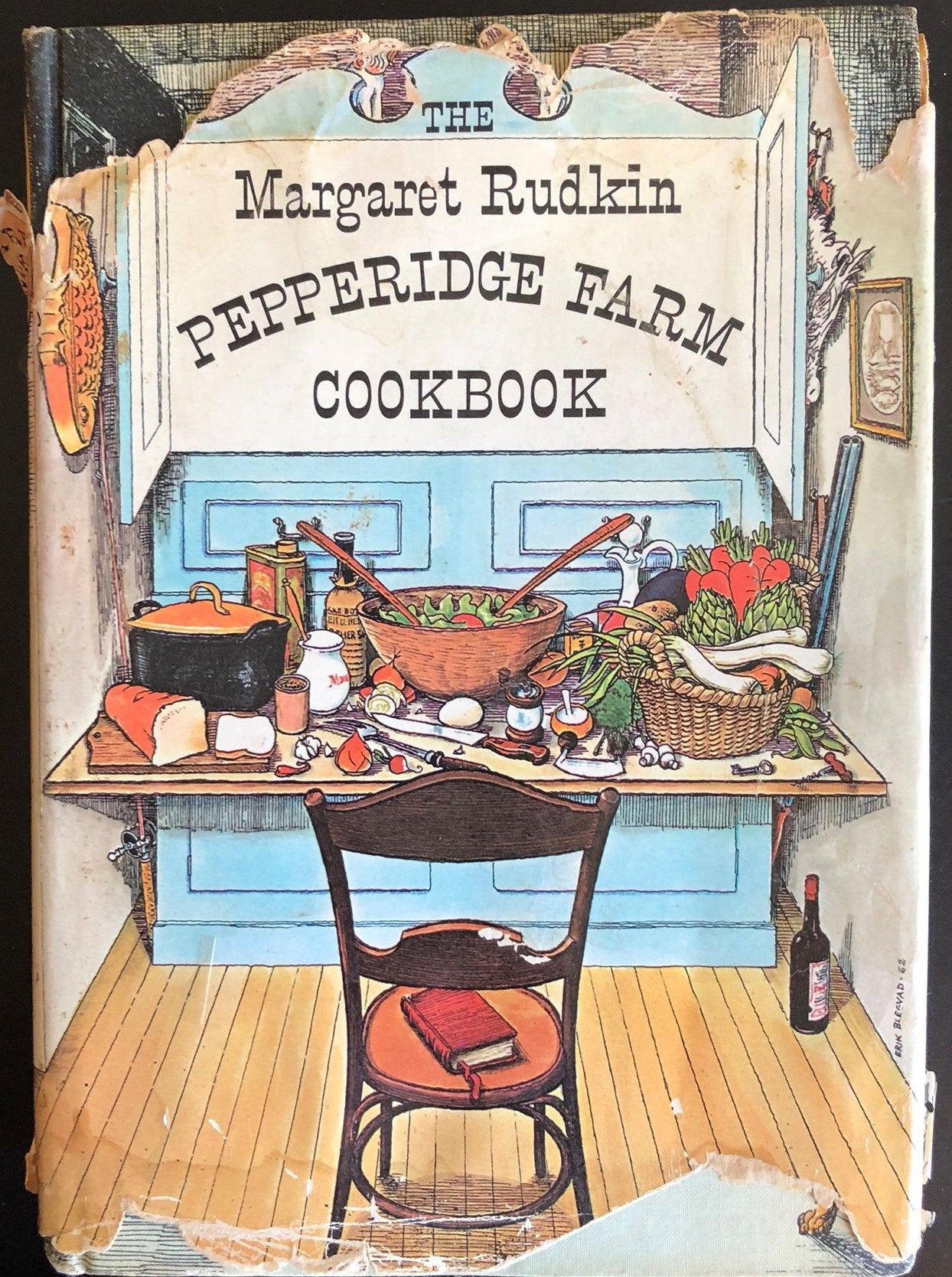

Take, for example, her 1963 Pepperidge Farm Cookbook. The eclectic book, with art from the Danish illustrator Erik Belgvad, was divided not by the traditional courses but into life stages: Childhood, Country Life, Pepperidge Farm, Ireland. And peculiarly, wedged in between those memoir-ish chapters of recipes and stories, was a fourth section: “Cooking from Antique Cookbooks.” It included vintage recipes from the 1475 Venetian cookbook De Honesta Voluptate et Valetudine, or “Virtuous Enjoyment and Good Health,” by Bartholomaeus de Platina, printed side by side with modern updates. The original was written in Latin; Rudkin tracked down a young professor to translate it for her. It made the New York Times best seller list.

“A remark often heard at the supermarket is, ‘anything put out by Pepperidge Farm is bound to be good,’ and this cookbook is up to the standard,” one book review in the Rocky Mount Telegram noted. Rudkin had something of a knack for turning obscure good taste into mass-market appeal.

According to company folklore, Rudkin started baking preservative-free whole wheat bread in the 1930s when her youngest son, Mark, developed severe food allergies, which the family doctor attributed to store-bought bread. These days, that’s a familiar line—the sickness of modernity sparking an epiphany to re-create something old-fashioned, and therefore healthier—for all sorts of post-industrial entrepreneurial origin stories, from artisanal gum to natural beauty companies to organic diapers.

But there’s another line in that story, too, that goes beyond the restlessness of maternal love. Rudkin’s husband, Henry Albert, a New York City stockbroker, was injured in a polo accident and couldn’t work for six months. The incident, coupled with the stock market crash of 1929, meant that Rudkin wasn’t just endeavoring to care for the health of one of her three sons, but for the financial survival of her entire family. The Rudkins sold apples and turkeys before launching their bread business.

Rudkin’s eventual success was not attributable solely to the quality of her bread, either. She’d graduated valedictorian of her Queens public high school class and worked as a bookkeeper at the brokerage firm McClure, Jones & Co, where she met her future husband. “Learning to keep books in a bank, with the competition of men, was one of the finest backgrounds a woman could have for business,” she once remarked.

In the early years of their marriage, the Rudkins did well financially, and in 1926, they bought a 125-acre farm in Fairfield, Connecticut, dubbed Pepperidge Farm after an old pepperidge tree on the property. Neither of them had any kind of country background, but that didn’t stop them from learning how to make sauerkraut and jams, churn butter, and raise and butcher their own livestock. She wrote to the Department of Agriculture for government pamphlets on “killing, curing and corning pork, and another one all about beef.” She brought the same gusto and experimental zeal to bread baking after talking to an allergist about fresh, stone-ground wheat—rich in the miraculous vitamin B1—instead of other processed flours.

Her first attempts at making bread, in 1937, didn’t go easily. “That first loaf should have been sent to the Smithsonian Institution as a sample of bread from the Stone Age for it was hard as a rock and about one inch high,” she wrote with characteristic wry humor in her cookbook. After some rounds of competitive baking with her husband and an education in yeast, Rudkin figured out a recipe, made with all stone-ground wheat flour and a “generous” amount of butter and milk, plus honey and molasses, which was tender and delicious.

She first bought wheat berries and milled them in a coffee grinder, and then later found local gristmills, including a water-powered one in South Sudbury, Massachusetts, to stone-grind them. For a later recipe, she showed this unerring commitment to ingredients, writing: “First, find some way to get sun-ripened, hard high-country wheat berries. Next, hunt for an old grist mill where they will grind your flour for you fresh the morning the day you bake.” After sampling Rudkin’s “health bread,” her family doctor was so taken with it that he ordered some for himself and other patients.

Rudkin started working with other doctors after that, in the process launching an American passion for whole wheat bread at a time when white bread was the only thing on the grocery-store shelves. She sold her first loaf to her local grocer, Mercurio’s, in Fairfield, and charged 25 cents—instead of the standard 10 cents—despite the grocer’s protests to cover her premium ingredients. It was also the Depression. That didn’t matter: Soon the phone was ringing with other grocers on the other end. Rudkin started with one assistant and a hand-turned mixing pail in her farmhouse kitchen, later moving operations from her home kitchen to ovens installed in one of the abandoned horse stables on their property, and eventually opening a baking facility, where the dough was still hand-kneaded.

She attributed its success to a combination of “quality and timing”—with the advent of commercial food products, women had stopped making bread at home, but there was nothing at the level of homemade in the grocery stores yet. By the end of the first year, she was selling 4,000 loaves per week, and within a decade, Pepperidge Farm was making 40,000 loaves per hour in a new specially designed production plant in Norwalk, Connecticut. Her husband, who hand-delivered orders on his way to Wall Street in the early years, eventually managed Pepperidge Farm’s finances and marketing, and two of their sons, Henry, Jr., and William, both joined the company after attending Yale and completing their wartime service.

Growth wasn’t a straight trajectory up. During World War II, instead of lowering the quality of her bread in response to wartime food rationing, Rudkin chose to limit production, according to a 1961 profile in the Iowa City Press-Citizen, to maintain the integrity of the ingredients: “93-score [Grade AA] dairy butter, fresh eggs, fresh whole milk, unsulphered molasses, and dark sweet honey.”

Rudkin’s curiosity, later marked by her including antique recipes in her cookbook, led her and her husband to sail to Europe. There she discovered chocolate cookies made by the Delacre Company, which supplied the Belgium Royal House. (It was on another trip to Europe that she found fish-shaped crackers in Switzerland.) Rudkin somehow convinced Delacre to allow Pepperidge Farm to use its “secret” recipes, imported a 150-foot cookie oven from Belgium, and brought over Belgian engineers and quality-control men to oversee production, introducing six cookies at the end of 1955: the now discontinued Capri, Biarritz, Venice, and Dresden, as well as Brussels and the simple, crunchy butter cookie Bordeaux, which are still produced today in the Distinctive collection, along with 15 other varieties, like the chocolate-and-pecan-topped Geneva. “Her insistence on high-quality ingredients was a breakthrough for American cookie lovers,” wrote Los Angeles Times food columnist Richard Sax.

Rudkin’s innovations weren’t strictly in the culinary realm. Before the advent of second-wave feminism, she was encouraging women to work and hiring them to acclimate the American public to the very idea of women in the workplace. In the early 1940s, she was offering “sound advice for other women who want to go into business for themselves,” inspiring an article titled “We, the Women,” which bemoaned that the business world would not hire women despite the capabilities they demonstrated in managing the home. Rudkin also hired housewives in the early days of her baking operation. “Look at what a bunch of women over 40 have done,” she told the AP in 1943 of the 125 women working in her bread bakery. “None of us had training or business experience. Most of us have children and home responsibilities. But we’re running this business and making it pay.”

She offered her workers flexible hours: Unmarried women preferred to work early in the morning so that they could do their farm chores in daylight, while married women with older children preferred to take shifts after school when the older children could look after the younger ones. She advocated the work of the housewife as good preparation for running a business later in life: “knowledge of how to buy well, use food properly and prevent waste, maintain cleanliness, routine, and system.” Later, when women started working in factories during World War II, she advocated for them there, too. “I don’t believe there is any job women can’t do,” she told the Edinburg Daily Courier in 1942, when women started working during the war. “They handle machines as well as men and they’re marvelous to work with.”

In the 1950s, decades before women moved into the workplace en masse, she told one interviewer that it was important to have someone “capable” to take care of the children at home and that children who grew up with a working mother learned how to be adaptable, responsible and mature. “Work and Stay Young, Noted Grandmother Advises; Says Boredom Women’s Enemy,” read one headline of Rudkin after she received the Medallion of Honor at the Women’s International Exposition. In 1960, Rudkin sold Pepperidge Farm, then reaching annual profits of $1.3 million and sales of $32 million, to Campbell Soup Company for a reported $28 million (over $237 million today), becoming the company’s first female board member. Rudkin passed away of breast cancer in 1967, following her husband’s death a year prior at the age of 81, leaving the management of the company to their sons, who eventually died too. But while she was alive, Margaret never lost her fire.

“Nobody’s going to retire me to a rocking chair and shawl,” she told the AP when asked in 1958 if she would retire. “They’ll have to tie me down first. That sort of thing may have been all right for [James] Whistler’s mother, but not for Maggie Rudkin.” How else to describe this woman than utterly distinctive?

What We Talk About When We Talk About American Food. In this column, Mari Uyehara covers American food at unique cultural moments and historical turns, great and small.