The starchy dough is an everyday staple of several West African countries, and making it can be a physical and mental test of focus, strength, and stamina.

While most folks watched in confusion, my heart couldn’t help but swell with pride at chef Eric Adjepong’s victory in the most recent season of Top Chef, when he made fufu with Congolese red sauce. At last, jollof rice—arguably one of the most famous foods from West Africa and a primer of sorts for those too timid to try other foods from these countries—was getting a much-needed break from the spotlight. As is true for many first-generation Ghanaians, fufu was something I grew up eating. Its mellow flavor can be best described as potato-like, with a hint of the tropics. Its dense, stretchy, and velvet-like texture was always accompanied by assorted soups, mostly made with a fragrant foundation of tomatoes, onions, peppers, and bay leaves.

Fufu typically refers to a starchy, smooth, gently cooked dough, but each version has its own characteristics, from Senegal to Cameroon, Puerto Rico to Brazil. It’s traveled across lands and forcibly migrated across oceans, transforming along the way. In West and Central Africa, fufu can be made from a wide variety of starchy tubers, plants, or grains—such as green plantain, cassava, cocoyam, corn, or semolina—which can come in fresh, fermented, or powdered forms.

The version I grew up with in New Jersey was made with a mild, imperceptibly flavored powder that was reconstituted with water and cooked. But when I moved to Ghana to live with my grandparents at age seven, I saw firsthand that fufu was much more dynamic than any reconstituted powder could be.

Women pounding fufu in Lomé, Togo

While fufu’s ingredients vary among regions in Ghana, it’s typically made with a mix of boiled plantain, cocoyam, and indigenous African yam or cassava, in a waduro and woma, traditional tools best described as a large mortar and an accompanying pestle that can range between five and seven feet high. Making fufu is a labor of love and a physical and mental test of focus, strength, and stamina. In a world that praises fast and easy meals, it is neither.

Once the plantain and cassava are boiled and tender, the driver sits behind the waduro, adding plantain pieces with a bit of water while the pounder uses the woma to smash the pieces, releasing the starches until it’s a soft, smooth mass. This is repeated with the cassava, then both are combined. The pounder and driver must be in sync, being careful not to apply too little or too much pressure (unless you want to break someone’s fingers) or add in pieces too quickly, which results in a lumpy product. Once the fufu is pounded, it’s transferred to a bowl, sprinkled with a bit of water to prevent the fufu from sticking, and shaped by hand. It takes about an hour to transform tubers and plantain into soft, smooth oblong shapes that give slightly when touched, then bounce back.

As a kid, this process endlessly fascinated me, so I was ecstatic when my grandmother finally let me try pounding. As a piece of plantain was placed into the waduro, I used all the might my body could muster, and the plantain flew out with such velocity that my grandmother startled. Needless to say, I was benched à la Tristan Thompson shortly after, until I was able to handle pounding with little assistance.

Fufu is as physical to eat as it is to make; it is a tactile food, meant to be eaten with your right hand and swallowed without chewing. It becomes the perfect flavor vehicle for a variety of hearty, intricately seasoned soups, some made with freshly ground peanut butter and heightened with a kick of whole Scotch bonnet peppers bobbing on the surface, others with red palmnut puree, seasoned with funky, umami-packed dawadawa and dried fish. As Essie Bartels, creator of Essiespice, a specialty sauce company that sources ingredients from Africa, explains: “You can literally eat fufu every single day and it’ll take on a new character with each new soup.”

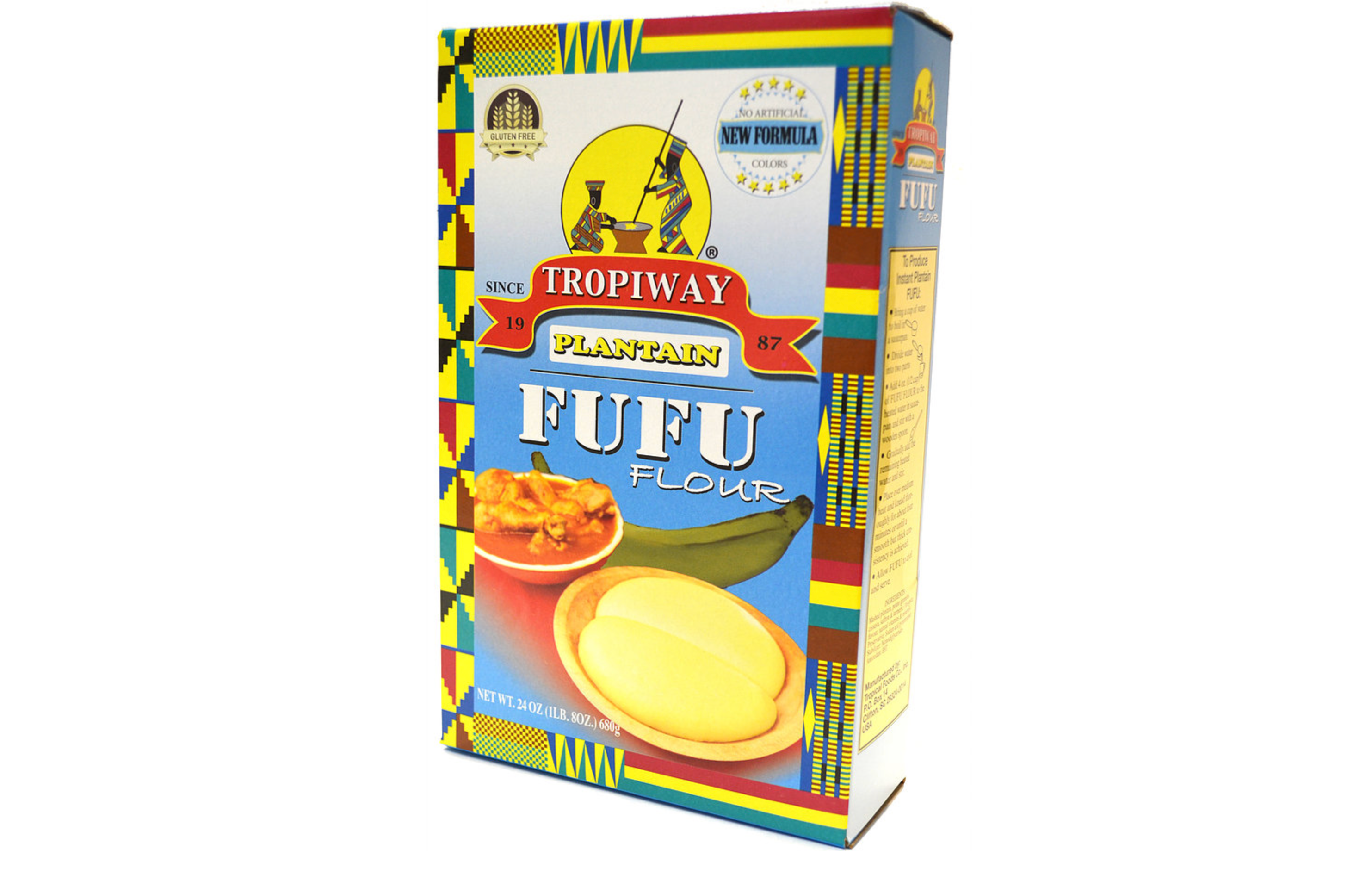

Tropiway’s flour is mixed with water and kneaded in a saucepan over heat to make fufu.

Despite my own love for fufu, making it traditionally outside of Ghana is nearly impossible. The woma and waduro are heavy and require an ample amount of space, which makes usage and storage impractical. Our home has experimented with a variety of substitutes, like potato starch and powdered oats, that never hit the mark, but Tropiway’s Fufu Flour has been a standard in my house for as long as I can remember. Made with a blend of plantain flour, potato starch, and cassava flour, Tropiway’s flour is even tinted with a hint of saffron and turmeric to mimic that familiar yellow hue that would otherwise come from fresh plantains. All you need is water and a few minutes on the stove or microwave to create fufu. Created by Edward Ofori, a Ghanaian food researcher, his invention still reigns supreme in most Ghanaian households across the world today—so much so that there are now counterfeit warnings on the brand’s site.

In spite of the convenience of a solution that comes in a box, many home cooks haven’t stopped experimenting. Trudy Arhin, who lives in Richmond, Virginia, found that it took a cocktail of flours to get the right texture: smooth and pliable, yet firm enough to maintain its shape when eaten with hearty soups. “I use the [fufu flour] box, but I use oatmeal powder for that added texture that most boxes lack.”

A few years ago, my mom learned of a new fufu-making technique from her friend, who swore by blending plantain and cassava with a little bit of water, then kneading the mixture over the stove until it thickened. This also happens to be the only technique Ghanaian food blogger Joana Yeboah-Acheampong of Aftrad Village Kitchen has used since moving from Ghana to the U.K. “My husband prefers this method, as he’s such a purist for the traditional version—it needs to taste close to the real thing.”

While I was initially skeptical, I tried it—and I was shocked. Even the little plantain seeds I remembered as a kid were in there. They always reminded me of the Ghanaian flag: black stars suspended in a canary galaxy.