There was a time before the Smiths and Bauhaus were replaced by bland electropop picked by a Spotify algorithm. A time when coffeehouses were where you went to think.

The Highland Coffee House smelled like chocolate and cinnamon and clove cigarettes and roasted nuts. The windows were tall and arched, offering blurred views of Highland Avenue with its battered row houses and a dive bar called Gert’s Playpen that I never dared enter. There was an old piano that music students and wistful old professors would play sometimes. There were shelves filled with musty books and a complete set of encyclopedias. There were Boston ferns everywhere. It was a shabby and welcoming place, a place that wanted to evoke the bohemian decor of a 19th-century European coffeehouse, even though it was just a mile or so from the University of Cincinnati.

I was 16 the first time I went to Highland, just old enough to drive my Grand Prix from the tony east-side suburb where I lived to the dilapidated 19th-century Italianate where it was located. I would go there with friends after track practice; I would go alone with the local alt-weekly and a pack of Djarums; I would go with an older college student I was dating, the one who once gave me a copy of Siddhartha and said it would change my life forever. It did. I would order Viennese coffee or cappuccinos, a mocha java sundae, or—depending on if I knew the waiter or not—an Amstel Light.

The soundtrack at Highland was evocative of its time—in this case the mid-1980s—a mix of the Smiths and Siouxsie and the Banshees, Sisters of Mercy and Bauhaus. The kind of bands I loved listening to, even though I might get back into my car and jam a Bon Jovi or Van Halen cassette into my stereo. It was never lost on me that the kids who hung out at Highland were more dedicated to being “different” than I was. They rebelled more against their Reaganite parents than I did. They didn’t enjoy their four-bedroom Colonial Revivals as much as I enjoyed mine. They didn’t cherish the silence of the suburbs, the mature trees, and the green ChemLawned yards as much as I cherished them. While I loved Cincinnati, they wanted to leave, through an acceptance to an art school in New York or Savannah, or maybe a few years squatting in an abandoned warehouse in New York or Chicago.

There were other coffee shops like Highland in Cincinnati. There was Sitwell’s, named for the British poet Edith Sitwell and owned by an attractive redheaded woman with corkscrew curls who, incensed by Reagan’s election, had left Cincinnati for Poland and then East Germany before returning home to open a coffeehouse modeled after the ones she found in Berlin. I would go there in the afternoons and eat salami, cream cheese, and cucumber sandwiches slathered in dill-ranch dressing. I would watch a local writer named Steve make like Edith herself, composing his own verse, which he often read on the public radio show he hosted on Sunday nights.

I suppose places like Highland and Sitwell’s were the dive bars of my youth. Little escape hatches I could walk into and be awakened by a deep conversation with a friend and a jolt or two of caffeine. To me, they were as peaceful as a public park—pre-digital-age paradises where your headspace was safe from the sudden invasion of an infuriating tweet or push alert. These were places where you could lose yourself in a novel or a Spin magazine article, places where you could ponder a Morrissey lyric or an overheard conversation, places where you could think.

Really think.

I was thinking about these places the other day as I sat at a table at the coffee shop in my neighborhood in Brooklyn. A sterile, minimalist box, with chalky-white painted drywall devoid of artwork or flyers for drummers or dog-walking services. There were no shabbily dressed professors. There were no renegade house plants. The wood floors were newly varnished; the tables square chunks on metal pedestals, not a sofa or an Archie Bunker easy chair to be seen. The place had all the charm of a Supercuts grand opening. But that isn’t surprising these days.

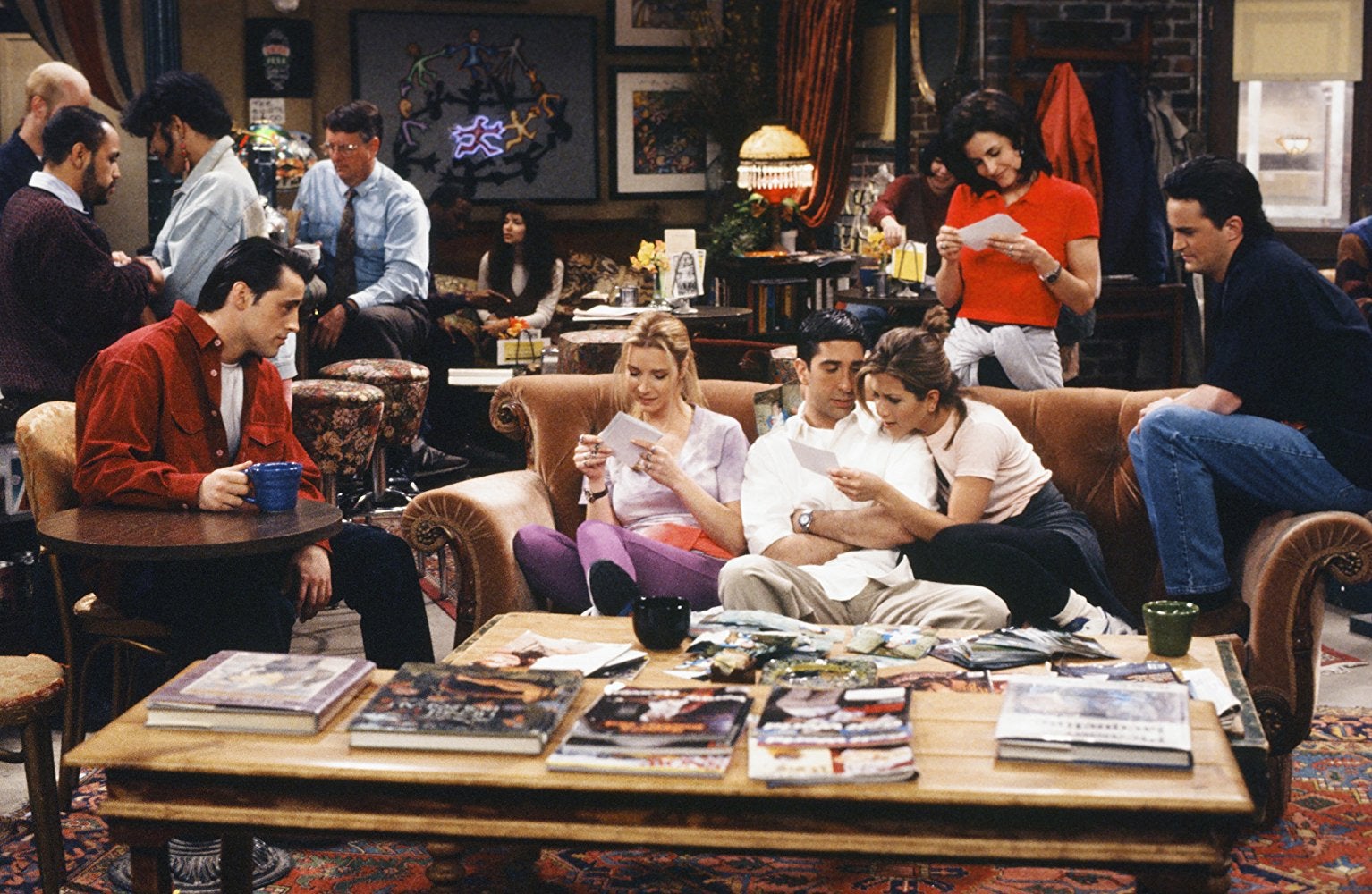

In the past few decades, coffee shops have changed as much as the coffee itself. As we ride high on the third wave of poured-over, Burr-grindered beans, we’ve forgotten just how much the places where those beans are served have changed, too. I don’t know what happened, really. I suppose it was a combination of the Starbucks revolution of the early ’90s paired with the pop-culture perception of coffeehouses as mainstream hangouts thanks to TV shows like Friends, where Central Perk seemed like almost a mockery of everything I held dear with its Paris Salon–meets–Pottery Barn decor. There were no outcasts hanging out with Ross. Watching the show in college, I imagined that the misanthropic barista, Gunther, once worked at a place like Highland but was forced to look for another job after it closed to make way for a Starbucks. While most viewers cheered for Ross and Rachel, I cheered for Gunther.

By 1993, when Frasier came on the air, coffee shops had taken on a distinctly Seattle vibe—sophisticated spaces where architects and psychiatrists and urban planners could sip half-caff hazelnut lattes on rainy days while Chet Baker’s “Let’s Get Lost” whispered through the Bose speakers perched above.

But even those places are disappearing now. Most of the new coffee shops I frequent, whether they’re in New York or L.A., San Francisco or, yes, Cincinnati, offer none of the escape or comfort that Highland or Sitwell’s once did (and, thank God, both are still open). Sure, they might have a wall of exposed brick, and some art for sale, hung and perfectly spaced above your table. The Sisters of Mercy and Bauhaus have been replaced by Spotify-fueled EDM and electro-pop that’s about as stimulating as Muzak. But who cares? These shops aren’t about feeling things. They are about the source of the semi-washed coffee beans and the detailed brewing techniques of their coffee. The most prevalent sound you’ll hear is the soft patter of your fingertips on a MacBook Air. The din of conversation is a mere distraction, one that can be remedied only by noise-canceling headphones. But there are still places where that’s not the case, even though they’re dying off at the same rate as dive bars and diners.

Last month, after meeting up with an old friend, I stopped by Cafe Reggio in Greenwich Village on my way back to the subway. I hadn’t been there in years, though it used to be one of my most sacred hangouts when I moved to New York 15 years ago. With its creaky floors, mismatched lighting, and thick, chipped plaster walls, it always reminded me of Highland and therefore of home. My mind was a jumble of anxieties that day. I’d lost myself in a social media meltdown lately, developing an exasperated, inarticulate persona that had nothing to do with who I really am. I felt gut-punched by our dying democracy. I felt angry about anger. I needed a break from myself; I needed to remember who I was.

Toppling into a bistro chair behind a round marble table, I tucked my phone in my messenger bag and placed it on the chair across from me, as far away as possible. The place was crowded with locals, mostly older, and, judging by their accents, largely European tourists. Looking around, I noticed a kid, probably 20 or so, reading a tattered paperback. He seemed like a time traveler.

I ordered an espresso, and it arrived a few minutes later in a chipped ceramic cup. The espresso was dirty and bitter and sweet, and the bite reminded me of the first time I’d ever tasted one. And while I had a book tucked inside my bag, I decided to leave it there. I wanted to take the place in. Give thanks that it still existed. I wanted to remember what it felt like to be an unplugged teenager, listening to a Smiths song in the ’80s. I wanted to go back to a place where I didn’t belong. A place where I could think.