A nervous home cook, and veteran cookbook writer, does what he does best when preparing to eat raw scallops at home. He worriedly waits for sickness to strike.

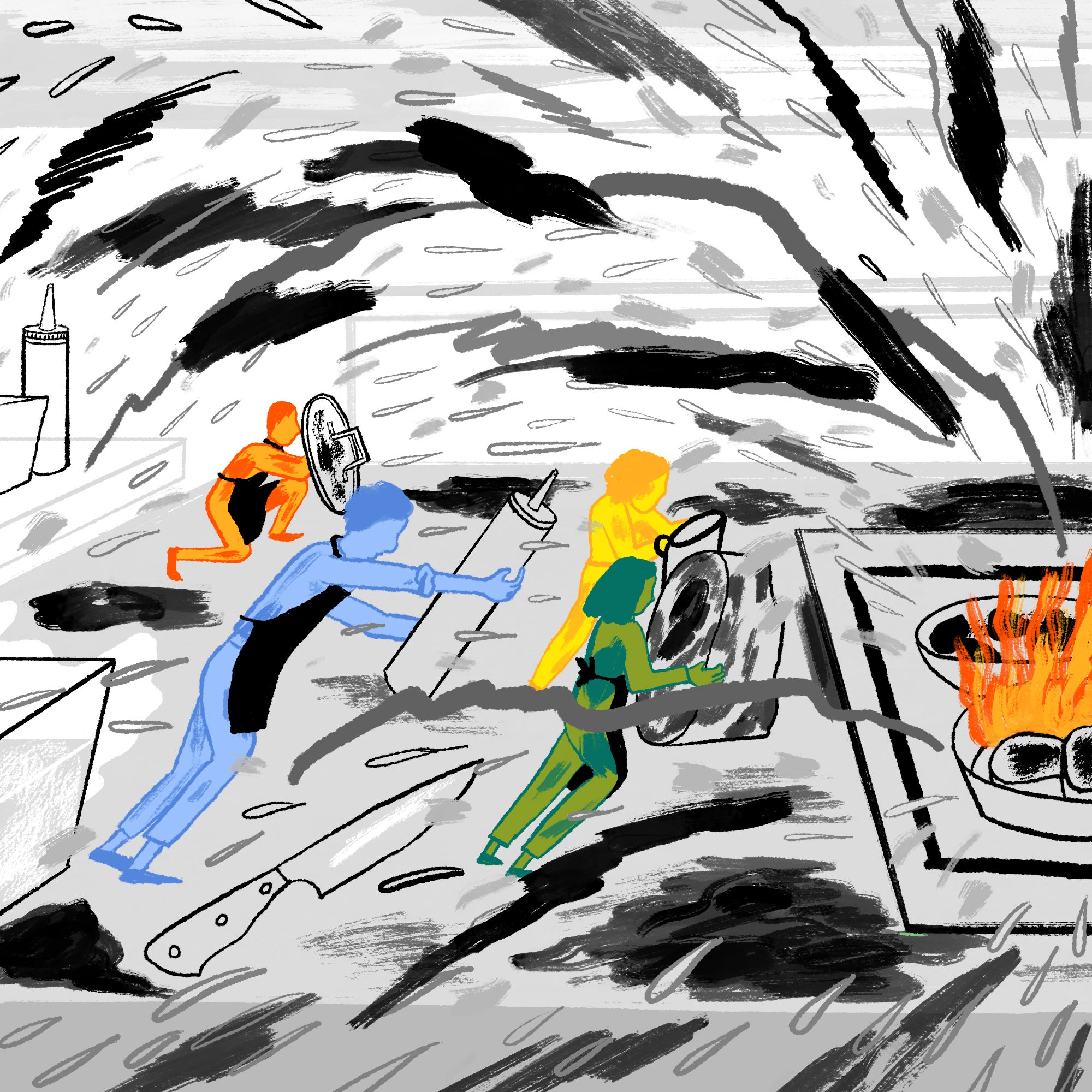

To the deskbound among us, chefs can seem like warriors, navigating a nightly gauntlet of well-whetted knives, hulking humans, and eyelash-singeing fire. To the pathologically worried, they can seem downright insane.

Because I fall into both of these categories, I’m frequently in awe of those who choose to work in small, hot, dangerous places for a living, just as I’m disturbed by their continual and flagrant disregard for the tenets of my anxiety.

As a cookbook collaborator, I’ve stood by as Dale Talde, of Talde and Top Chef fame, stoked my death-by-scalding-fat phobia, using a vat of hot oil as a laboratory to test the fry-ability of everything from miso to lettuce to canned biscuit dough. I’ve faked nonchalance as Andy Ricker, emperor of Pok Pok restaurants, walked me through the making of Thai soured meats, for which you essentially salt the heck out of some pork and leave it in a warm place for a few days. I’ve winced as April Bloomfield defied my most fundamental assumption of culinary safety—eating raw poultry equals death by salmonella—assessing the seasoning of uncooked chicken by swiping at the flesh with a finger and giving it a lick. After dutifully scribbling down Dale’s ideal frying oil temperature or the amount of salt Andy adds to the pork, I pivot to a series of questions that ultimately boil down to one: If I do what you say, will I die?

They insist I will not, and their confidence is contagious, especially while I’m still in their thrall. Watching them work, I like to fantasize about being the kind of home cook who placidly carves mold from a rib eye I dry-aged myself, or skims off white globules from the surface of lacto-fermenting cabbage. “Don’t worry,” I imagine assuring my wife. “It’s not evidence of rapidly multiplying mold spores brimming with mycotoxins—it’s just a little kahm yeast.”

Left alone, however, I’m often paralyzed by worry. While I’m plenty afraid of erupting fat and surging flame, my primary concerns tend toward the microbial. I frantically inspect two-day-old salmon fillets for signs of spoilage. I intentionally overcook burgers—making me a heretic to the swaggering food writer contingent—just in case. I obsessively scrub wooden spoons in an attempt to banish germs, bacteria, protozoa, and any other infinitesimal beasts that I imagine lurk in the porous material, waiting to do me harm. To anyone tempted to chef-splain that I worry too much, go ahead. Seriously, it soothes me when people share information that contradicts my runaway thoughts, just as it calms me to hear that the pain in the lower left side of my abdomen isn’t appendicitis, because the appendix is actually on the right. Food might be politics and community, medicine and fuel, but it can also be fear on a plate.

In a strange twist, my cowardice is limited to my own endeavors. When I’m eating food that someone else prepared, I’m like a smokejumper mixed with a Navy Seal crossed with a woman during childbirth. I eagerly eat brains and snouts, kidneys and lungs, ant eggs and bee larvae. I eat chili made from bear meat that a friend gets from his local taxidermist, trichinosis be damned. How I can slurp the raw blood soup called luu at a dusty restaurant in Chiang Mai yet experience heart palpitations when a bite of chicken I roasted myself reveals flesh that’s a little too pink near the bone is a question for my therapist. Say what you want about the neurotics who avoid wheat, corn syrup, or beans—at least there’s consistency to their paranoia.

Rawness is a particular trigger for both my delight and my angst. Thanks in some part to these same chefs, I’ve found that raw is the best way to eat countless creatures. Unadulterated by heat, clams are at their briniest, sea urchin at its creamiest, and horse at its horsiest. Befitting the peculiar logic of my worry, I’ll take down uncooked anything, anywhere—still-writhing shrimp at a fancy sushi place, spicy tuna rolls at the airport—except at home. When I’m the one responsible for the final safety check, raw flesh warps from pristine perfection into potential purveyor of parasites. I don’t trust myself to decide whether a seawater scent is reassurance or rot, whether that dark spot on a shucked clam is siphon or sign of vibrio vulnificus.

This is a shame, because I really want to eat raw creatures at home, particularly those from the sea. Without the restaurant markup, they’re a much more affordable indulgence. Since they don’t require cooking, they align nicely with my less-is-more culinary ethos—not in the Alice Waters sense, but in the less cooking means more TV sense. Plus, cooking seafood is a high-wire act that I don’t relish. I’ve overcooked too many $25 fillets of wild tautog, and I can’t take it anymore.

I have a particular affection for raw scallops, which taste briny and sweet and have a lovely delicate texture. Accordingly, I have no patience for monsters who subject the mollusk to even a brief spin in a hot pan (or to an acidic marinade, in an attempt to have it both ways). Cooking makes its texture rubbery and intensifies its flavor, marring simple pleasure with complexity, like a film buff explaining the symbolism in Blue Velvet. For years, I’ve dreamed of enjoying scallops this way at my own table, rather than waiting for the occasional splurge at a sushi bar or restaurant run by a chef whose name I kind of remember from an issue of Bon Appétit. Really, what I was after was the permission implicit in a pricey meal, the comfort that comes from pretending there is some ominiscient gatekeeper who can say for sure that all will be well.

This is the point in the article where I’m supposed to reveal that some digging into the scientific literature on bacteria or a frank discussion about parasites with a Deep Throat at the FDA caused me to change my ways, and now I am a sauerkraut-making, tartare-serving kitchen commando. The truth is, unless a super-powered freezer has killed the microscopic evildoers by dragging your bivalves deep into subzero territory, they might make you sick. So because the only thing more powerful than my fear of food is my love for consuming it, I suggest seeking out the illusion of peace of mind.

That’s what I did, at last. I found a guru in the fish guy at my local farmers’ market, who doesn’t just stand behind a bed of crushed ice but knows how the scallops are caught and when the boat last went out. In this case, the freshness factor is about flavor—that is, about determining if I should eat his scallops raw, not whether I can—so I also inquire, indirectly, about parasites, which thrive in even the freshest fish: “Would you eat these raw?” I ask and when he answers in the affirmative, I give him the Larry David staredown to make sure he’s given the question sufficient thought.

My scallops sanctioned, I take them home, slice them, and dribble on a mixture of lemon juice and olive oil. As I eat my fill of what at a restaurant would, along with a froufrou garnish, be a $16, three-bite share plate, I think to myself, If I’m still alive tomorrow morning, I’m definitely doing this again.