The one-arm cookbook genre finally finds its audience.

Like the news, cookbooks often put me in a sour mood. After confronting one too many recipes in a row that call for carrot peeling, garlic mincing, or artichoke turning, I start to grumble: Why aren’t there more cookbooks written for people like me?

As even casual readers of my work probably understand, the reason is probably that there aren’t many people like me—eager home cooks who are flush with ambition, hampered by the usual time constraints, and in possession of only one fully operational arm. My lopsided brethren and I—the congenitally malformed, veterans of war, gangrene survivors, pirates, et al—constitute something of a niche readership whose numbers fall somewhere in between those of avid at-home canard à la presse practitioners and amateur miso makers. You might be surprised, then, to learn of a small and not-growing genre of cookbooks that ostensibly appeal to those lacking in limb.

I know I was surprised when, after witnessing my precarious peeling of winter squash, a friend half-jokingly suggested a Google search for cookbooks for people with one arm and the probe actually turned up a few intriguing titles. For a second, I wondered whether some clever publisher had rustled up recipes from the world’s most fortitudinous chefs, such as Michael Caines, who lost his right arm in a car accident and whose Michelin-starred food puts my acceptable salads to shame. Alas.

The conceit of The One-Armed Cook, for instance, is clear before you even open the endearingly spiral-bound volume, published in 2005. The illustrated cover depicts a woman at the stove holding a spoon in one hand and a baby with the other. She is stirring a pot full of steaming red liquid that, if you ask this overly anxious dad, is a little too close to Junior’s tiny feet. Before I had kids, I might have dismissed the book’s concept out of hand. Because why would anyone hold a baby while she cooked when she could simply plunk the baby in a high chair, where he would presumably sit quietly and perhaps catch up on some reading? The nightly nightmare that is dinnertime at my apartment has convinced me that any and all advice is welcome, and almost makes me forgive the authors’ reliance on jarred minced garlic and frozen chopped onions in virtually every dish, from the Lentil and Vegetable Stew to the Broccoli Rabe and Spaghetti Egg Bake.

I felt a momentary thrill, meanwhile, at the cover of One Handed Cooks, which shows three unpaired appendages reaching for various treats. Yet as a brief flip-through made clear, all cooks’ extremities were accounted for, and its trio of Australian authors had merely revived the cutesy kid-as-impediment trope. Published 11 years after The One-Armed Cook, the book’s content is more of-the-moment, with recipes like Satay Chicken Skewers and Raspberry Pikelets (essentially pancakes in the Down Under vernacular) made with spelt flour, with nary a package of frozen chopped onions or “Simply Potatoes” in sight. On the book’s promise to help raise healthy, happy eaters, I will reserve judgment, having not cooked from it and being no expert on feeding my own kid, who eats approximately three things unless I employ some Jessica Seinfeld–ian trickery like blending various vegetables into tomato sauce. But I will admit to giggling out loud at the thought of presenting my dogged little pastavore with a plate of Salmon and Ricotta Cakes.

I don’t mind, by the way, the appropriation of my curious condition for the purpose of metaphor, just as I don’t hold it against friends and colleagues when they ask if I need a hand (indeed I do), complain that they’re shorthanded (a little too on the nose), or claim they can perform some task with one hand tied behind their backs (not as well as I can). What bothers me is how thin the authors stretch it. Because while the book’s recipes are uncomplicated enough, many still require the kind of mundane prep—hunching over to cube raw chicken breasts for those skewers, grating zucchini and lemon zest for those salmon cakes—that, as a permanent resident of the particular state of being in question, I do occasionally resent. I’ll also remind the able among you that when an actual one-armed cook scoops up a fussing baby, he has nothing left for spoons and knives.

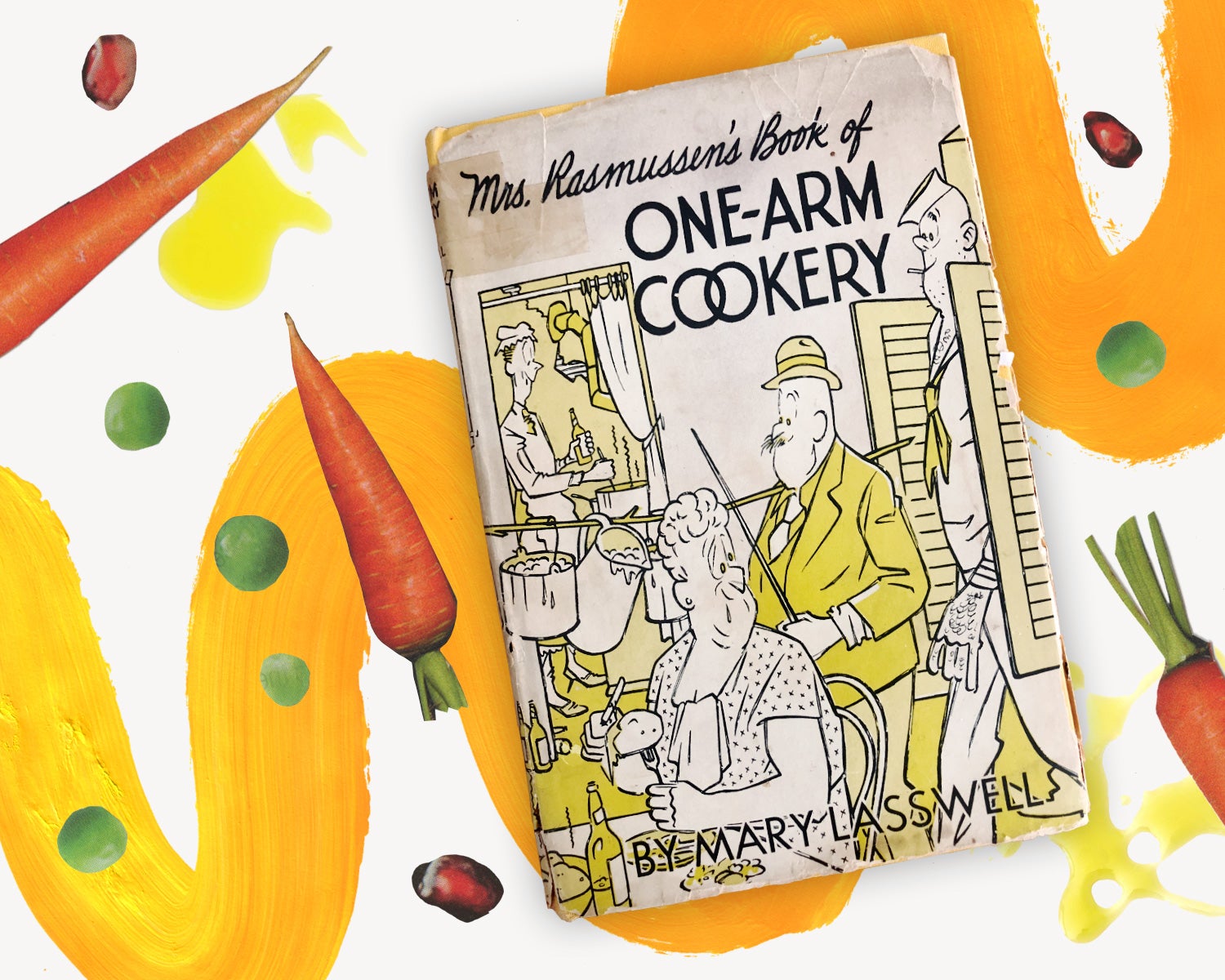

A better match for my style of home cooking is Mrs. Rasmussen’s Book of One-Arm Cookery. Penned by the late writer and humorist Mary Lasswell, the book acts as a sort of companion to her 1942 novel Suds in Your Eye, a tale of three suds-swilling elderly women who live together, penniless but not without pep, in a junkyard in Southern California. After World War II ended—and the rationing that defined the dreary home cooking of the early ’40s was discontinued—Lasswell published this collection of real recipes from the fictional Mrs. Rasmussen, the culinary wiz among the trio of merry old ladies, whose signature was turning modest foodstuffs into marvelous feasts. And despite a passing mention in the September 29, 1961, issue of Life magazine, where the cookbook was described as a book “for people whose other arm is missing or otherwise occupied hugging one’s spouse,” the arm not referenced in the title is clearly meant to be hugging a bottle of beer.

I felt a momentary thrill, meanwhile, at the cover of One Handed Cooks, which shows three unpaired appendages reaching for various treats.

If the book’s aim was making cooking fun again, it worked on at least one reader, the essayist and James Beard Foundation hall-of-famer Betty Fussell, who encountered the book as a young woman and wrote in The New York Times that it had inspired her embrace of the stove: “To a college kid, Lasswell’s instructions were heaven-sent: ‘Take a bottle of cold beer out of the icebox. Place an ashtray handy to the stove.’”

It’s unfair to judge One-Arm Cookery against its more modern counterparts, since time tends to turn foible into fascination. Were it not for the intervening decades, for example, I would be tempted to kvetch that anchovy-topped pizza is translated for the layperson as “Italian Fish Pie” while “Pfeffernuss” is offered with no such elucidation (it’s a German iced cookie) and in a batch size that requires seven pounds of flour, and that the task of filleting herrings for Rasmussen’s Rollmops with a drink in hand is almost as implausible as that of consuming Fiji Island Spread—a concoction of liverwurst, mango chutney, horseradish, and enough “mayonnaise to make a smooth paste”—without one.

I might technically be incapable of chugging while cooking, but nowadays I do spend my most peaceful moments in the kitchen on weekends with both kids in bed and a beer on the counter. Even with my good hand free, I don’t feel like chopping but I do feel like cooking, only in part because I feel like eating. I bet you can relate.