A blood-splashed culinary school binder recalls the timelessness of French culinary pedagogy and the bold awfulness of ’80s restaurant food.

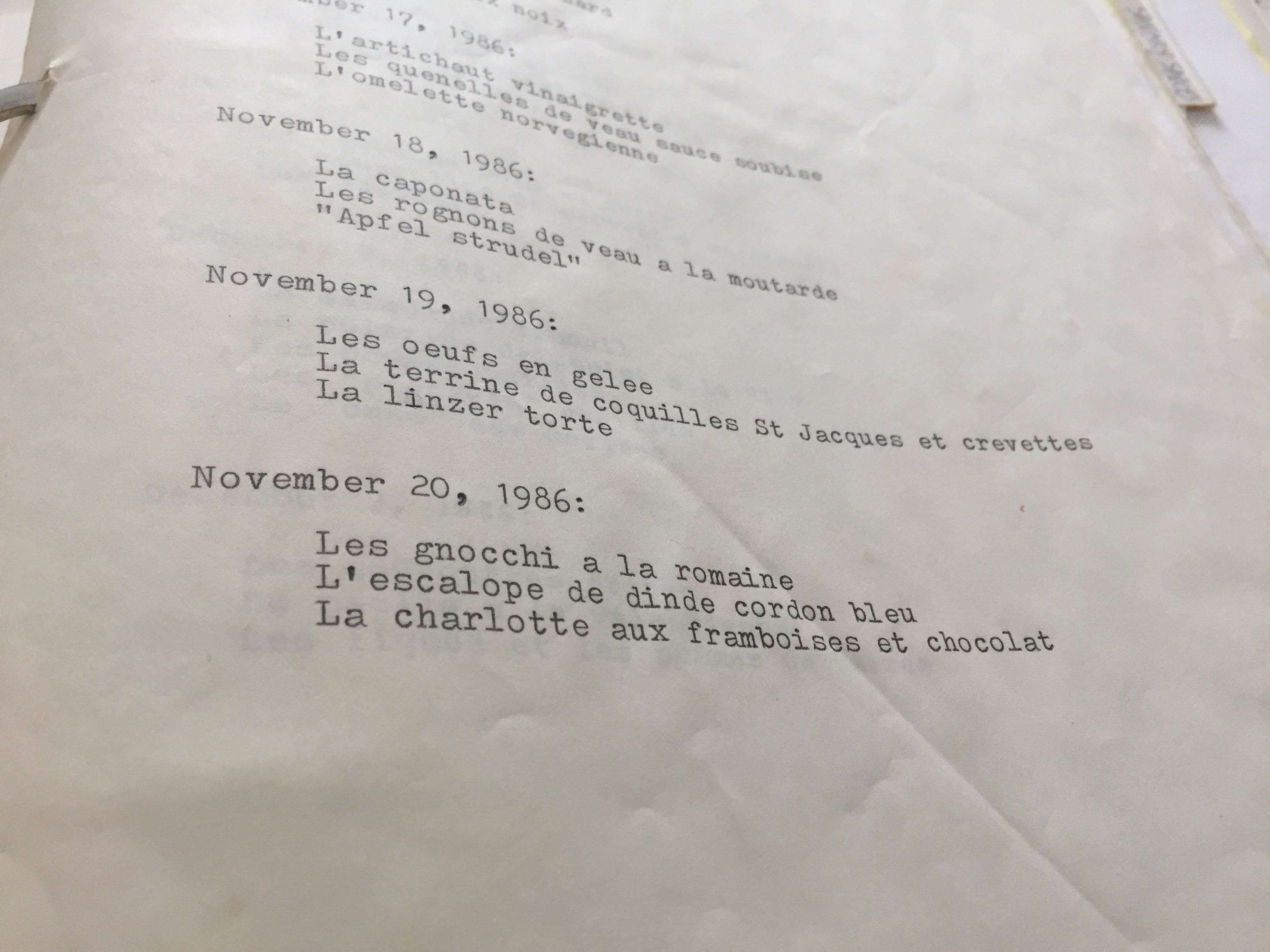

On November 20, 1986, I ate this lunch: semolina gnocchi, turkey cordon bleu, and a raspberry and chocolate Bavarian cream charlotte for dessert. How do I know? Because right afterward I went home to type up the menu—with corresponding recipes—on a Selectric typewriter and put the pages in a three-ring binder. By the end of the week I had polished off eggs in aspic, Linzer torte, veal kidneys à la moutarde, duck consommé, and gateau St. Honoré. There was even an entry for veal mousse quenelles in sauce soubise, which, 30 years later, sounds like a Lynchian food nightmare.

That binder—three inches thick, filled with 250 hole-punched pages—is the one artifact that remains from my days as a culinary student. In 1986 I was 25 years old and had made the unlikely decision to attend cooking school. Unlikely because I had graduated from a boast-worthy college, had my fun traveling and working abroad, and then settled into a respectable job with a market research firm, which would have made me serious money had I stayed with it. As far as my Jewish-doctor father was concerned, my only possible next step could be law school or business school. When I told him that I wanted to attend L’Académie de Cuisine in Bethesda, Maryland, and then go work as a restaurant cook, he just about plotzed.

Yet a few months after that conversation I stood at a culinary classroom station outfitted with a cutting board and a gas burner, one of 14 students who ranged from a government lawyer changing careers to a young woman fresh out of high school. I wore a white polyester chef coat and black-and-white polyester houndstooth pants. I had, I’m sorry to admit, a shoulder-length mullet and a pair of glasses with lenses as large as demitasse saucers. Laid before me was a gray sole, both its eyes staring unevenly back up as flatfish are wont to do, and a six-inch carbon-steel Henckels boning knife.

Our instructor, a wild-haired man named Pascal Dionot, taught us that day to extract four fillets; that was the easy part. The bones went into the stockpot with a bouquet garni (aromatic herbs) and mirepoix (chopped vegetables) to make a fish fumet. We thickened the fumet with flour to make a velouté, and finally—with the addition of wine, heavy cream and peeled muscat grapes—prepared a sauce Véronique to glaze over the fillets.

Pascal was the younger brother of school director François Dionot. With his French beak nose, trimmed moustache, and bulbous eyes, he looked like a character from a Renoir painting. He might walk into the classroom with a whole lamb carcass draped over his shoulder and show us how to break it down. We might spend hours turning small potatoes into seven-sided footballs for pommes persillées or crushing lobster shells for bisque. He was a phenomenal and passionate instructor, as good as any I had in college.

Pascal had been chef at the Hay-Adams, the hotel across the street from the White House where visiting heads of state often stayed. He had trained at the Plaza Athénée in Paris and had its top-secret pike quenelle recipe to prove it. That recipe began with a panade, the elastic dough used for cream puffs, and a whole lot of pike mousse. Because pike has so many tiny bones, we first pushed the mousse through a tamis, a wooden hoop fitted with a taut wire mesh. That process took muscle and more than an hour. Once completed, we formed the quenelles using two spoons and placed them in a gratin dish over bisque-like sauce Nantua, and then blast roasted them in an oven until they puffed and glazed. It may have been the best thing I’ve ever eaten in my life.

By the end of the year I had the knife skills to debone a chicken for a galantine, I had a low-paying job at a restaurant I could never afford to dine in, and I had that binder. It is an earnest document of my year of lunch, of coursework divided into “theory” and “technique,” with the daily menus neatly listed in the first pages, then tabbed chapters with labels like “veal,” “stock charts,” and “dessert basics.”

The savory recipes were often little more than lists of ingredients with a sentence or two to outline the preparation. Blanquette de veau: simmer veal in white stock with mirepoix and bouquet garni; strain and reserve veal; thicken with roux; add cream, veal, sautéed mushrooms and pearl onions. The pastry recipes were just as terse but with measurements—all solids by weight and liquids by volume. Today, the binder remains my only connection to that time. It followed me through my eight-year career as a cook, when I raided it for nightly dinner specials, and then my next one as a food writer, when I dipped into it for column inspiration.

When I look through its chocolate- and blood-stained pages now, I see both the timelessness of French culinary pedagogy and the bold awfulness of ’80s restaurant food. There are charts of mother sauces with suggested applications and dishes that today read like the culinary equivalent of shoulder pads.

Think lobster ravioli in screaming yellow saffron beurre blanc surrounded by snow peas splayed like fingers. Think raspberry everything, from salad dressing to dessert sauce.

A page from the author’s well-used recipe binder

Think mousse. Fish mousse, chicken mousse, lemon mousse, leek mousse, and the one mousse to rule them all: white chocolate mousse. That was because of where we were and when we were. During Reagan’s ’80s, the ultimate dessert consisted of a foot-high cookie tuile filled with white chocolate mousse—extra points if it rested on a sunburst design of crème anglaise and raspberry coulis. Coulis? If you’re over, say, 45, you’ll remember this sauce of pureed fruit or vegetable as a menu cliché, the “artisanal” of the ’80s.

As we advanced to more difficult pastry, the Reagans’ legendary pastry chef, Roland Mesnier, came to the school to show us how to make blown-sugar green apples to fill with white chocolate mousse and raspberries. Guests at the White House—one imagines James Baker and George Will—would tap the apples with a spoon to break them open and watch the mousse trickle down.

Other top chefs came to the school to teach, nearly all them French. Jean-Louis Palladin, then perhaps the nation’s most famous chef, came to demonstrate eggplant soup with duck testicles, which even got the lawyer snickering. He got so angry when his chive custards overcooked, he threw them against a wall. Besides the occasional duck testicle, what was restaurant food like in the ’80s? Well, we loved color for the sake of color. We served red and yellow pepper cream soup side by side in the same bowl. We striped beet and spinach pasta dough until it looked like Regency wallpaper.

In the ’80s, sauces were thin and glossy—beurre blanc for savory dishes, crème anglaise for sweet—and we rolled the 12-inch plates in our hands so the sauce would cover the full surface like a mirror. In the ’80s, we loved fresh berry tarts sheathed in apricot glaze and tarte tatin with crème fraîche. We served butter-glazed vegetable garnishes arranged like flower bouquets. We routinely made pommes soufflés—those wondrous balloon puffs of fried potato that arrived at the table in a cootie-catcher-folded white napkin. “Very good for your food cost,” Pascal said. “You can charge $4 for those.”

All these dishes fill the pages of my cooking school notebook, which is both a relic of the ’80s and a testament to the foundational importance of French cooking. In my later career as a restaurant critic, I’d see echoes of my lessons in every bowl of soup, every reduction sauce, every tweaked flavor combination. I will always know that sauce hollandaise counts as one of the five mother sauces, and if you add a dry reduction of tarragon and shallot you get sauce béarnaise, which is delicious with beef, and then if you add tomato paste you have sauce choron, which is delicious with fish.

Over the years I’ve consulted my notebook less frequently—usually when I want to re-create an elaborate dessert, such as the marjolaine, a tall layering of dacquoise with chocolate, hazelnut, and vanilla creams that was invented by chef Ferdinand Point. I’m not sure why it called out to me from the bookshelf recently, but lately I’ve been turning back the clock. One day last year I got a bee in my bonnet for real puff pastry, folded and turned six times, and I made a puffy, glorious apple pithiviers decorated with Hillary Clinton’s campaign logo. I wanted to make lobster bisque by pureeing the base, shells and all, in a blender and straining it through cheesecloth. I broke the blender, but the soup was good.

After 30 years of cooking as a chef and food writer, as a sometimes thrower of elaborate dinner parties and daily dinner maker for three kids, I one day felt a sudden pang of desire to revisit the very dishes that launched me into this life. It was time to re-create a menu, to revisit one of those ridiculous lunches I ate standing up at my cooking station. November 20, 1986, seemed as good a date as any to start with.

Menu of November 20, 1986, L’Academie de Cuisine

First course: Gnocchi à la romaine

This version of gnocchi, made with semolina rather than potato, has always been popular in France. The recipe instructed me to prepare an eggy dough, spread it in a parchment-lined sheet pan to chill, and cut into thick rounds with a pastry cutter. I overlapped the rounds in a gratin dish and baked them with cheese and tomato concassée (peeled, diced, and sauteed) until they puffed and browned. It was tasty enough, but my 30-years-later self found the project not worth the effort.

Main course: Turkey cordon bleu

This was taught as the kind of special cooks should serve to bring food cost down. It was also a quick, easy main course because we spent most of our class time that day preparing a complicated dessert. Still, what a great rediscovery. Recipe below.

Dessert: Raspberry and chocolate charlotte

Notes: Holy hell. If Proust’s madeleine could trigger a repressed trauma, that would describe my feelings about trying this dessert again. It consists of a layer of génoise (sponge cake), topped with one layer of gelatin-set chocolate mousse and one layer raspberry Bavarian cream, then surrounded with ladyfingers. That wiggly texture and ubiquitous flavor combination—chocolate, cream, bad frozen raspberries—was every dessert in the ’80s. It took Jean-Georges Vongerichten’s liquid-center chocolate cake to break this unfortunate chocolate paradigm.

Photo by Antonis Achilleos