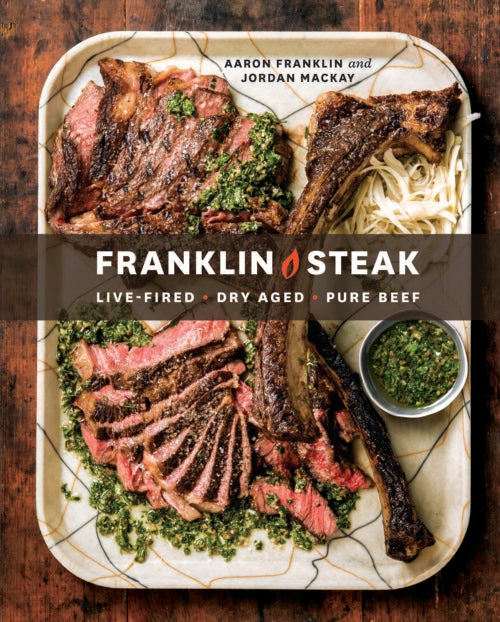

Aaron Franklin has shifted his passion for barbecue to steak, and he has some strong opinions to share in a new cookbook.

In the eight years I worked at Ten Speed Press, I edited 55 books on food and drink. Somewhere in that time—was it after book 40 or 45?—I’ll admit it, I started to get cocky about my kitchen skills.

It’s fitting, then, that one of the very last cookbooks I edited, Aaron Franklin and Jordan Mackay’s Franklin Steak, upended basically everything I thought I knew about steak and live-fire cooking, and showed me just how much I still had to learn.

Aaron Franklin is the James Beard Award–winning pitmaster and owner of Franklin Barbecue in Austin, Texas. Maybe you’ve heard about his restaurant and its legendary, yes-it’s-worth-the-four-hour-wait brisket; maybe you’ve seen Franklin on his PBS show, BBQ With Franklin, or on Anthony Bourdain’s shows, or alongside Jon Favreau in the movie Chef.

Franklin is rightly considered to be the king of Texas barbecue, and a genius when it comes to cooking beef with fire. His first cookbook, Franklin Barbecue, spent weeks on the New York Times best-seller list and was named Eater’s Cookbook of the Year. In other words, when they tell you how to cook beef, you listen.

“The only people this book won’t please are the sous vide people.”

That said, I cannot forget the extreme discomfort I felt the first time I read through the manuscript. When they told me I was wrong about when to flip meat, I was confused. When they told me I was wrong about when I should take the meat out of the refrigerator to temper it, I was alarmed. When they told me I was wrong about how long I need to rest the meat before carving, I was straight-up angry, imagining all the one-star Amazon reviews this crazy book was going to elicit.

When I ask Franklin and Mackay if they set out to write a controversial book (I believe my exact words were, “What kind of shit are you trying to stir up?!”), the famously kind, generous, and down-to-earth Franklin was quick to jump in.

“Hey, quite the opposite! We want to please everyone!”

“The only people this book won’t please are the sous vide people,” adds Mackay, his equally kind but slightly snarkier coauthor. “We didn’t care about them.” (Franklin Steak comes down pretty hard on sous vide: At one point, Franklin and Mackay compare this type of gadget-y cooking to relieving yourself in a Japanese bidet-style toilet: cool and different, yes, but how much better are the results, really?)

“Look, everyone knows how to cook a steak,” Mackay admits. “It’s the simplest thing in the world.” But, he points out, it’s important to question so-called “conventional wisdom” in all things, steak included. “Things change! Think about it: For a long time, the greatest cut of meat was said to be the filet mignon. But in recent years, everyone is all about the rib eye. Now it’s conventional wisdom that the rib eye is the best cut. Of course, we push against that in the book as well.”

This book is not here to tell you that you’ve been living a lie and that the way your grandpappy taught you to cook a steak is stupid. Rather, it’s a product of Aaron and Jordan’s obsessiveness, their tendency to overanalyze things and geek out over seemingly minute details. And yes, their willingness to challenge truths we hold to be self-evident. Now that the book is published and out in the world for all to see (or get fired up about), I chatted with the authors about a few of the steak-cooking myths they decided to debunk.

Conventional Wisdom: Remove your steak from the fridge and temper it for 20 minutes before cooking.

Franklin Steak Says: Twenty minutes won’t make any difference at all. And in some cases, it’s better to throw your steak on cold!

“For super-thin pieces, I’ll sometimes throw it in the freezer, wait until it’s really, really cold, and then put it on the grill,” says Franklin.

The first time I read this piece of advice in the manuscript, I was certain it was a mistake. But the more I think about it, the more Aaron’s counterintuitive advice makes sense. If you’re cooking a steak thinner than one inch, say a skirt, hanger, or even a thinly cut strip, and if your goal is rare or medium-rare doneness, then you want to slow the cooking of the interior to give yourself enough time to develop a proper crust on the outside of the steak.

A giant piece of meat, by contrast—say a bone-in tomahawk rib eye, which might weigh as much as 2 1/2 pounds, or a standing rib roast—benefits from tempering, since it will take quite a bit longer for the interior of the meat to reach doneness, and you risk drying out the exterior if you start grilling meat when the interior is super-cold. But for a piece of meat that massive to reach room temperature could take hours. Personally, I’m fine leaving a hunk of meat on the counter for that long. The USDA, not so much. “We did check the gradient on how fast a steak warms on the counter,” says Mackay, “and it’s very slow. Taking it out of the fridge 30 minutes before you cook it, or even an hour, especially for a thick piece of meat with a bone in, ultimately does very little.”

My takeaway? If I’m cooking something thin, I’m not going to worry about tempering at all. For thicker steaks, I’m going to let them rest out of the refrigerator on my counter for an hour or three (unless my food-safety-conscious husband catches me), since less than that doesn’t make a difference.

Conventional Wisdom: Don’t flip your steak too often—let it rest in one place on the grates. You know, for those magazine-worthy grill marks that are clear sign of the perfectly cooked steak.

Franklin Steak Says: Those grill marks are a lie. The goal is an allover crust, so flip early and flip often.

By now we’ve all heard of the magical Maillard reaction (thanks Kenji and Samin), the chemical process that creates that rich brown color and deep, pungent flavors of a well-browned steak or loaf of bread. According to Franklin Steak, “the Maillard reactions are often conflated with caramelization. Although both produce complex molecules and both are referred to as browning reactions based on the color they produce in food, they are different. Caramelization involves the simple breakdown of sugars, whereas the Maillard reactions, according to Harold McGee in On Food and Cooking, are all about the thousands of new, distinct compounds created when amino acids react with a carbohydrate or sugar molecule in the presence of high heat.”

The Maillard reaction is what makes the crusty exterior of a steak so delicious, and it is why we cook steak on a grill or in a cast-iron pan instead of in the microwave. Maillard happens where the surface of the steak meets the surface of the grill—so if you have beautiful cross-hatched grill marks, that means that you’ve missed out on Maillard wherever the steak isn’t marked.

“Just for fun, I always try to see how ’80s I can make my grill marks look on a steak,” says Franklin. “But then I start to flip a bunch, and they go away immediately. I really prefer to have Maillard across the entire steak, not just the grill marks.”

Mackay chimes in: “The whole steak should be a grill mark!” I immediately go to bumpersticker.com to get this, my new steak mantra, printed on a custom bumper sticker so I’ll never forget it.

Conventional Wisdom: Rest, rest, REST!

Conventional Wisdom: Rest, rest, REST!

Franklin Steak Says: As soon as you can touch your steak without burning your fingertip, slice the thing and serve.

I think it’s because I watched too much of Anthony Bourdain’s No Reservations when I was just a baby foodie, but whenever I pull a piece of meat off the grill, I start cursing and yelling at myself like a crazy person. “Do not f*&k this up, Emily. Don’t you dare carve that meat. Don’t even look at that f*&king knife. Walk away!!!”

Of course, at the heart of it, Tony was right: Slicing into a piece of meat hot off the grill is a bad idea. But I think he accidentally created a generation of meat-carving-phobes, like me: We all sit there, staring bug-eyed at our meat, terrified that if we slice it too soon, a tidal wave of juices will start pouring out, leaving behind a tragic, desiccated carcass that we will have to throw into the trash. “I ruined the steak, guys, I’m sorry. I guess we won’t have dinner tonight.”

I am very grateful to Franklin and Mackay for setting me straight: “If you can touch it, that means it’s rested,” Franklin tells me. “Steak tends to cool down pretty fast, anyway,” Mackay continues, placatingly. I hadn’t realized it, but even asking them how long I should rest my steak had made me start to sweat.

But at the end of the day, Franklin and Mackay aren’t here to chasten me, or make me feel bad about my steak-cooking ignorance. “When it comes to steak, the nostalgia factor is huge,” says Jordan. “It’s not just about the methods; steak is tied into everyone’s memory. You attach feelings and sensibilities to it.” Franklin agrees: “You see your dad or your grandpa or whoever cook things a certain way, whether it’s steak or barbecue, and you just say to yourself, Well, that’s how you do it. And then you get older, and if you’re me, you overanalyze things for many years, and you realize, Oh, maybe there is a better way indeed.” And there it is, the simple, beautiful promise of Franklin Steak: Conventional wisdom be damned. There is a better way.