The late, pioneering Chicago chef authored several cookbooks and collected thousands more.

When Charlie Trotter closed his eponymous Chicago restaurant in 2012, his plan was to travel the world and then enroll in graduate school in philosophy. He’d already been accepted to three programs, he said at the time. He didn’t rule out opening another restaurant someday, but one thing was perfectly clear: there would never be another Charlie Trotter’s.

In its heyday in the 1980s and ’90s, Charlie Trotter’s had been one of the country’s most influential restaurants. When it first opened in 1987, fine dining was mostly associated with French cuisine. Trotter had his own vision. “Cuisine is only about making foods taste the way they are supposed to taste,” he wrote. “That may seem obvious, but really it is not.” In practice, this meant keeping the classic French techniques, like roulades and reductions, but eliminating the cream and butter in favor of Japanese-style minimalism to let his ingredients—always the freshest and best he could find—taste most like themselves. He was, said the chef Wolfgang Puck, “the first American to do something new.”

Trotter was obsessive in his pursuit of excellence. He only served wine, never spirits, because he believed the harshness of distilled alcohol would damage diners’ palates. He banished walk-in coolers from his kitchen because, he argued, if you only use the freshest produce, refrigeration is unnecessary. He demanded that his cooks scrub the restaurant’s dumpster to keep the rats away. He routinely fired line cooks who didn’t perform to his standards, sometimes in the middle of service.

Trotter didn’t exempt his own physical comfort from this obsessiveness: he would sleep on the restaurant banquettes to save himself the trouble of interrupting his work to do something so mundane as commute home. In 1996, he took the number two spot on a Chicago magazine list of the city’s meanest people, right after Michael Jordan, another obsessive perfectionist. Trotter was annoyed—he thought he should have been first.

“The customer is rarely right,” he declared during a 2010 appearance on The Interview Show, a live talk show at the Chicago bar the Hideout. “That is why you must seize control of the circumstances and dominate every last detail to guarantee that they’re going to have a far better time than they ever would have had had they tried to control it themselves.”

The audience laughed, but it was true: customers did submit to his vision, traveling from all over the world to experience a meal at Charlie Trotter’s—and then tell everyone they knew that they had been there.

From Charlie Trotter’s Vegetables, published in 1996.

Over the years, Trotter’s methods of preparing highly technical tasting menus with seasonal and then-unusual ingredients—quinoa, microgreens—and his innovations like an all-vegetable degustation menu, shared plates, a sous vide machine, and a chef’s table in the kitchen so select customers could view the action close-up had become so widespread that, by the time the restaurant closed in 2012, food journalists had to remind everyone that he had gotten there first.

The food world had moved on to other enthusiasms, including the Spanish-led molecular gastronomy and later hyperlocal foraging evangelized by Noma’s René Redzepi and other European chefs. Meanwhile, Trotter’s reputation for exactitude had begun to seem less like a joke and more like an act of unnecessary cruelty. When he died in 2013, less than a year after the end of his famous restaurant, he was remembered not as a part of the contemporary culinary scene but as a relic of restaurant history.

But late last year, Alinea’s Grant Achatz, who’d had a brief but influential apprenticeship at Charlie Trotter’s in 1994, ran a tribute menu at his experimental restaurant Next. A few months later, Trotter’s son, Dylan, announced that he had rehabbed the twin townhouses on West Armitage Avenue that had housed the restaurant and was planning a series of pop-ups from celebrated chefs before reopening for good. The reboot would maintain Trotter’s philosophy using updated ingredients and techniques. It would be a Charlie Trotter’s for 2025.

All the excitement made me curious about what it had been like to eat at the original Trotter’s. I’d grown up in Chicago, but I’d been too young and uninterested (and also too poor) to eat there. However, Trotter had left behind a series of five cookbooks about the restaurant, starting with Charlie Trotter’s and followed by Vegetables, Seafood, Desserts, and Meat & Game. Achatz had been so inspired by the books that he had moved from Michigan to Chicago just to work with their author. Jason Hammel, the owner and executive chef of Lula Café, had learned to cook from them. This was the closest I was ever going to get.

The first book in the series, published in 1994, begins with a simple thesis. “It’s all about excellence, or at least working toward excellence. Early on in your approach to cooking—or to running a restaurant—you have to determine whether or not you are willing to commit fully and completely to the idea of the pursuit of excellence.” There are quotes from Fyodor Dostoyevsky and Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and references to the philosopher Jeremy Bentham. It’s clear that cooking like Charlie Trotter is a serious business. But I was comforted by the final lines of the introduction: “The recipes in this book are only a guide…. In fact, you may want to forget about the recipe specifics and use the photographs alone as your inspiration for putting together a meal.”

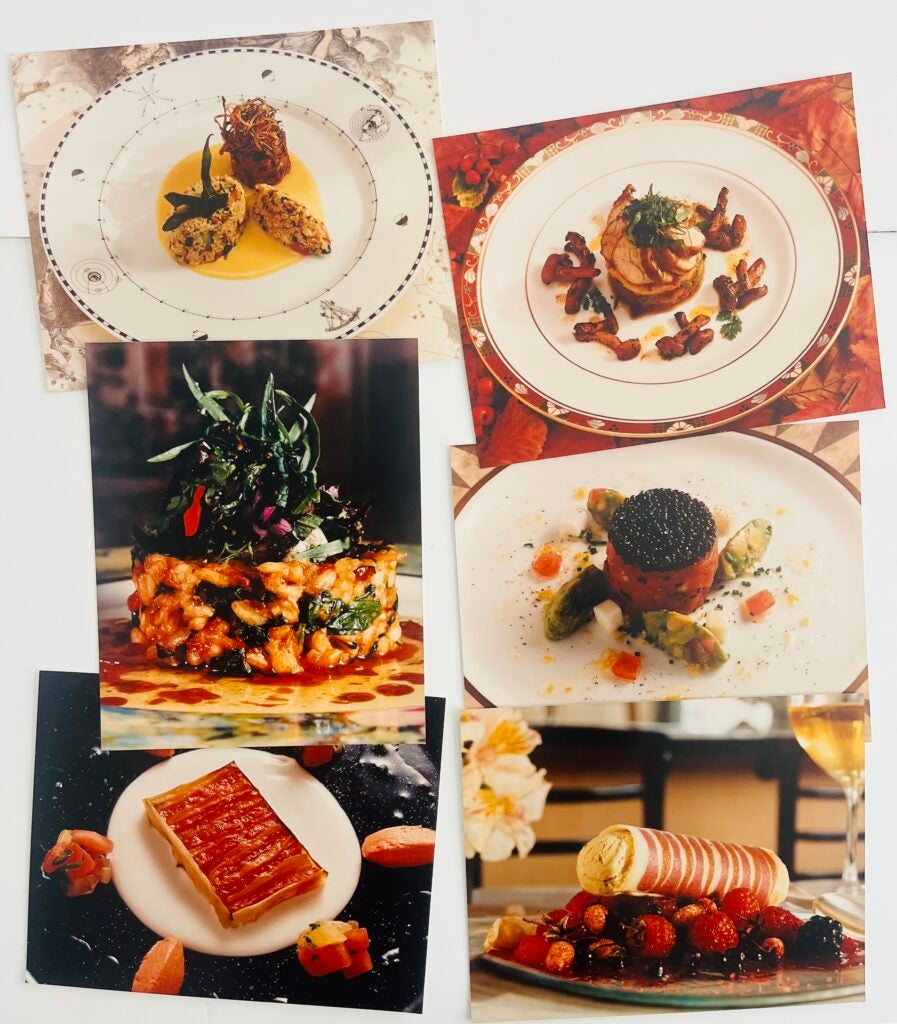

There were indeed photographs: full-color extreme close-ups of various dishes, so tight you can see the individual granules of salt and globules of fat. There are also photos of Trotter and his staff behind the scenes in the restaurant, working toward excellence, but these are in grainy black and white, as if to say, “These are the people who make the food, but it’s really the food that matters.” (All the photos were shot by Tim Turner, who would go on to win two James Beard Awards for his work, including one for Charlie Trotter’s Desserts.)

Color prints submitted to Ten Speed Press in 1992 with the original Charlie Trotter’s proposal. Photos: Tim Turner.

As soon as I started paging through the book, before I even read the headnotes of any recipes, I was quite certain I would never be able to recreate any of those dishes. Not the towers and terrines and roulades, not the perfectly twirled nests of noodles, and certainly not the peppered lamb loin with polenta, ratatouille, and bell pepper–infused lamb stock reduction, which resembled some sort of demented meat-and-vegetable carousel and reminded me that the ’90s were, in fact, a long time ago.

Demented meat carousels aside, it’s an exquisite book. The pages are sewn instead of glued so that the book stays open when you’re using it—“lay-flat binding,” in publishing parlance. The cover is what publishers call “true cloth,” not the simulated material that’s used in most hardcovers, and there’s a satin ribbon to use as a bookmark (heaven forbid you should spoil the splendor of this book by dog-earing the pages). The cover price reflected this high production value: it cost $50 (equivalent to about $110 today) when it was first published, an unprecedented sum for a cookbook at the time. It’s currently out of print.

It was also the first of its kind, says Matt Sartwell, owner of Kitchen Arts & Letters, an acclaimed culinary bookstore located on New York’s Upper East Side. There were a few other lavishly photographed American cookbooks before this one, notably New American Classics by Jeremiah Tower in 1986 and Coyote Cafe by Mark Miller in 1989, but none had the impact of Charlie Trotter’s. “They didn’t have the emphasis on the full-page food photography,” Sartwell says. “They didn’t show you what was on the plate in a way that said, ‘This is important.’”

Upon publication of Charlie Trotter’s, Sartwell remembers receiving calls from people all over the country who were looking for it. That first autumn, he sold several hundred copies, at a time when most titles sold five copies a month and a breakout book would sell 30 to 40.

It also inspired a flurry of larger-format, lavishly photographed cookbooks that people kept on their coffee tables instead of in their kitchens, most notably Thomas Keller’s The French Laundry Cookbook, first published in 1999, with 600,000 copies in print. Ironically, these books were all priced at $50 for a long time, even as the cost of book production increased. “There was this conviction that people wouldn’t pay more than that,” Sartwell says. “In some ways, I think it was very damaging to the American publishing industry. It meant that interesting projects didn’t happen because they would have had to have been priced above $50.”

So who was Charlie Trotter’s for? Surely it was not for a home cook. Or was it?

No, says Aaron Wehner, the current publisher of Ten Speed Press, which was the book’s original home. “It wasn’t about taking his recipes into the home kitchen. It was about documenting his food.”

Wehner, a publishing veteran who is currently executive vice president and director of business development at Crown Publishing Group, edited Charlie Trotter’s Meat & Game, the final book in the series, as a young editor, and he went on to work with Trotter on several subsequent books, including Raw and Home Cooking with Charlie Trotter. The series did not follow the standard editorial process at the time.

Typically, cookbook authors submitted a proposal to the publisher, and the editorial and production teams would shape the completed manuscript and design the finished book. But Charlie Trotter’s would arrive at Ten Speed with a fully formed creative vision behind it. In her initial letter to Ten Speed, dated February 24, 1992, and provided to me by Ten Speed, an independent editor named Terry Ann Neff proposed a radical copublishing arrangement wherein she and her team would edit and design the book, and Ten Speed would distribute it. (To note, TASTE is also part of Crown Publishing Group, although it is editorially independent.)

It was a win-win situation. “They got a packager who could do the whole thing really well and give Trotter the design that he wanted,” Sartwell, a veteran of the publishing industry himself, observes. “And Ten Speed didn’t have to deal with him changing his mind a thousand times.”

Charlie Trotter’s Seafood, published in 1997.

Trotter, of course, had the means to pay for complete control. His father, a tech entrepreneur, had given him significant funds, some $1.5 million, to open his own restaurant just five years after he stepped into a professional kitchen for the first time, and then helped him manage the financial side of his business. (His mother was also a regular presence at Charlie Trotter’s, greeting guests and checking on their meals like a maître d’.) By 1992, five years into the life of Charlie Trotter’s, Trotter had won the first of many James Beard Foundation Awards, and both he and his restaurant were famous, not just in Chicago but across America. About 60% of Trotter’s diners, by one estimation, came from outside Chicago.

This was all part of a growing national obsession in the ’90s with restaurants, and with chefs in particular. “Fine dining took off,” recalls Celia Sack, owner of Omnivore Books in San Francisco. “And it was important to talk about who was behind the food and those trends.” The interest in American chefs, she says, started on the West Coast, and Trotter was one of the first non-Californians to benefit from the wave of excitement.

But why go to all that trouble and expense just to document Trotter’s food instead of producing a book his fans could cook from?

Charlie Trotter loved cookbooks. After he died, his widow, Rochelle, donated his collection—more than 1,300 volumes—to the Chicago Public Library. Now the books live in a warehouse with the rest of the library’s special collections, but they’re available to view by request. Recently I visited the Special Collections Reading Room, tucked away in a quiet, temperature-controlled corner of the ninth floor of the central library downtown, to look at the books that had been classified as Trotter’s favorites. They were waiting for me in a half dozen archival boxes piled on a cart; a librarian provided me with pillows to rest the books on so I wouldn’t damage their spines.

I’m not sure what I was expecting—detailed marginalia, or maybe some old food stains or broken bindings that fell open to favorite recipes (or jokes, in the case of Good Health and Humor: Illustrated Jokes, an antique volume from 1912)—something that would give me special insight into the soul of Charlie Trotter. But most of the books, including Alinea, The French Laundry Cookbook, and The Vegetarian Epicure, were in pristine condition, except for personal inscriptions from their authors.

The only signs of life were in Trotter’s college-era copy of Moosewood Cookbook, which was stuffed with newspaper clippings in English and French, handwritten recipes (including one for cheesecake with a crust made from boxed cake mix), and a pamphlet entitled “Slim Meals” from the University of Wisconsin-Madison hospital nutrition clinic. Trotter apparently was either a very tidy cook or, after he outgrew Moosewood, he considered cookbooks to be something other than instruction manuals. But his relationship with cookbooks was also about more than simply collecting.

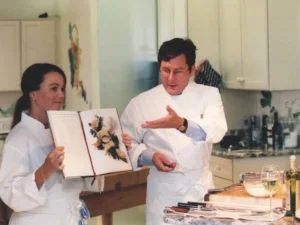

Charlie Trotter leading a cooking demo in the 1990s. Photo: Dylan Trotter.

At the top of the first box I opened was his very favorite cookbook of all time: Ma Gastronomie, a compilation of recipes by Fernand Point, chef-owner of La Pyramide, a Michelin-starred restaurant in Vienne, France, first published in 1969. (Trotter also owned a more recent English edition from 2008.)

“Charlie gave this book to I don’t know how many people,” says chef Norman Van Aken, Trotter’s mentor and friend. “Point was the most inspirational, fundamental chef for someone with a hyphenation between a European and American sensibility.” Which was what Trotter was, at least at first; the Asian influences would come later.

Point had a reputation for deep romanticism. He began every day by sipping from a bottle of Champagne while a barber trimmed his hair. The introduction to Ma Gastronomie warns, “Fernand Point’s recipes are not intended for beginners in the culinary arts…. Recipes are like love potions. There is an element of magic, and not everyone knows how to take advantage of it.” Point, however, believed that everyone should enjoy his food: Judith Jones recounted in her book Love Me, Feed Me that when she and a group of friends arrived at La Pyramide with a poodle named Nikki, Point greeted the dog with a kiss on the brow and made sure she had her fair share of every course. (I cannot imagine any dogs at Charlie Trotter’s.)

In many ways, Charlie Trotter’s resembles Ma Gastronomie. There are the close-up color portraits of dishes—though Point’s had touches of whimsy, like a crowd of crayfish attempting to scale a model of the restaurant’s namesake pyramide—and recipes that are also clearly not intended for beginners in the culinary arts. Trotter, like Point, wrote in a brisk and authoritative style that assumed the reader knew what he or she was doing and that basic skills did not need to be explained. In Ten Speed’s archives, Wehner found what he describes as “spirited back-and-forth” between Trotter’s team and the publisher, including this response to a query from a copy editor:

“When you note, for example, that ‘carrots are going to be very very hard to cut,’ he is at a loss. The person who finds carrots too hard to cut [a certain way] is certainly not going to make Charlie’s food.”

When the book first came out, Ted Allen, the future Queer Eye dining expert and Chopped host, made an attempt to cook from it with a group of friends and wrote an article for Chicago magazine about the experience. “It was just a comedy of errors,” Allen remembered years later in an interview with Eater. “People who smoked back then tapping ashes into the food by accident, and things going terribly wrong, and Charlie loved [the article].”

In many ways, Charlie Trotter’s resembles Ma Gastronomie.

Was Trotter’s own book a tribute to Point’s, I wondered? But then I saw other older French books in the collection in the same style; L’Envolée des Saveurs by Bernard Loiseau, from 1991, was especially beautiful. This kind of portfolio cookbook, says Sartwell, had been popular in Europe for a long time. The fundamental difference was that Trotter viewed his own cooking—which he described in Charlie Trotter’s as a blend of “European refinement regarding the pleasures of the table, American ingenuity and energy in operating a small enterprise, Japanese minimalism and poetic elegance in effecting a sensibility, and a modern approach to incorporating health and dietary concerns”—as a means of self-expression.

Trotter, says Van Aken, was also inspired by another very American art form. “Charlie’s models have always been jazz,” he says. “His favorite musical artists were Miles Davis and Bob Dylan. I think his most favorite quote by Miles was ‘I have to change. It’s like a curse.’ He was very fixated on the fact that he was not going to have a dish repeated.”

Some people buy jazz albums because they like their aesthetics. But others, especially musicians, buy them to study and find things to steal. For young American chefs, the Charlie Trotter’s series was sort of like that.

Jason Hammel of Chicago’s Lula Cafe.

Jason Hammel of Lula Cafe, which opened in 1998, was one of those chefs. “We literally stole ideas from [Charlie Trotter’s Vegetables] and made them our own,” he says. “Like the carrot and cardamom cakes. That was a combination that was really compelling to us.”

Hammel did more than swipe flavor combinations. By closely examining the book’s behind-the-scenes photos, Hammel was able to track down Trotter’s vegetable supplier, Cornille Produce (these were the days before farmers’ markets), where he saw ingredients like pattypan squash and baby turnips for the first time.

To date, the Charlie Trotter’s series has sold a combined 500,000 copies, says Wehner. But it was the first book that had the greatest impact, because it was unlike anything that had been published before.

The cookbook market has changed again, says Omnivore Books’s Sack. Restaurant cookbooks aren’t as popular as they used to be. Chefs are now encouraged to broaden their focus for home cooks, to be utilitarian, like in Trotter’s old copy of Moosewood, instead of inspiring and challenging other professionals. But Sack still keeps copies of Trotter’s books in her shop, and chefs do come in to buy them.

And then, eventually, she has noticed, they stop coming in to buy other chefs’ books. “They don’t need cookbooks anymore,” she says. “They’ve been imitating, and then they come into their own style.”

I thought about that when I saw Trotter’s copy of Ma Gastronomie. The jacket was torn, but the book itself was pristine. Had Trotter taken everything he’d needed to know and moved on? Did he expect that people would do that with his own book? The taste of food, after all, is ephemeral, like live jazz. A cookbook, like an album, is an attempt to preserve it so others can continue to engage with it after the moment is over.

I asked Hammel if that was his experience. “Books become useful to you and change your life,” he says. “It doesn’t mean you have to have a continuing relationship with them.” We accept this about novels, so why not about cookbooks? Recently, while moving books around, Hammel came across his old copy of Trotter’s 1999 book The Kitchen Sessions and flipped through the pages. “It had the same kind of nostalgic impact as seeing old pictures of my kids when they were little. Just like, ‘Oh my God, I remember this. Wasn’t this great?’”

And maybe that’s for the best. Even if Trotter were to come back today and reopen Charlie Trotter’s, it wouldn’t be the same. We taste differently now, in part because of all the chefs that first learned to cook from Charlie Trotter—the man, the restaurant, the cookbooks. And maybe that’s why all food writing, even the very best, falls just a little bit short: nothing will ever taste as good as we imagine it.