Stored in fancy vases. Cooked with care and finesse. Served in the Titanic’s first-class cabin. There were days when celery was not just boring crudité, but a luxury.

Though it’s the crucial third component of a mirepoix, cooked celery is one of the most universally hated vegetables. Most notable for its role as the log in ants on a log—or the garnish in a Bloody Mary—raw celery is the baby’s breath of crudités, the ligneous filler in the veggie tray, always stubbornly there, never really wanted.

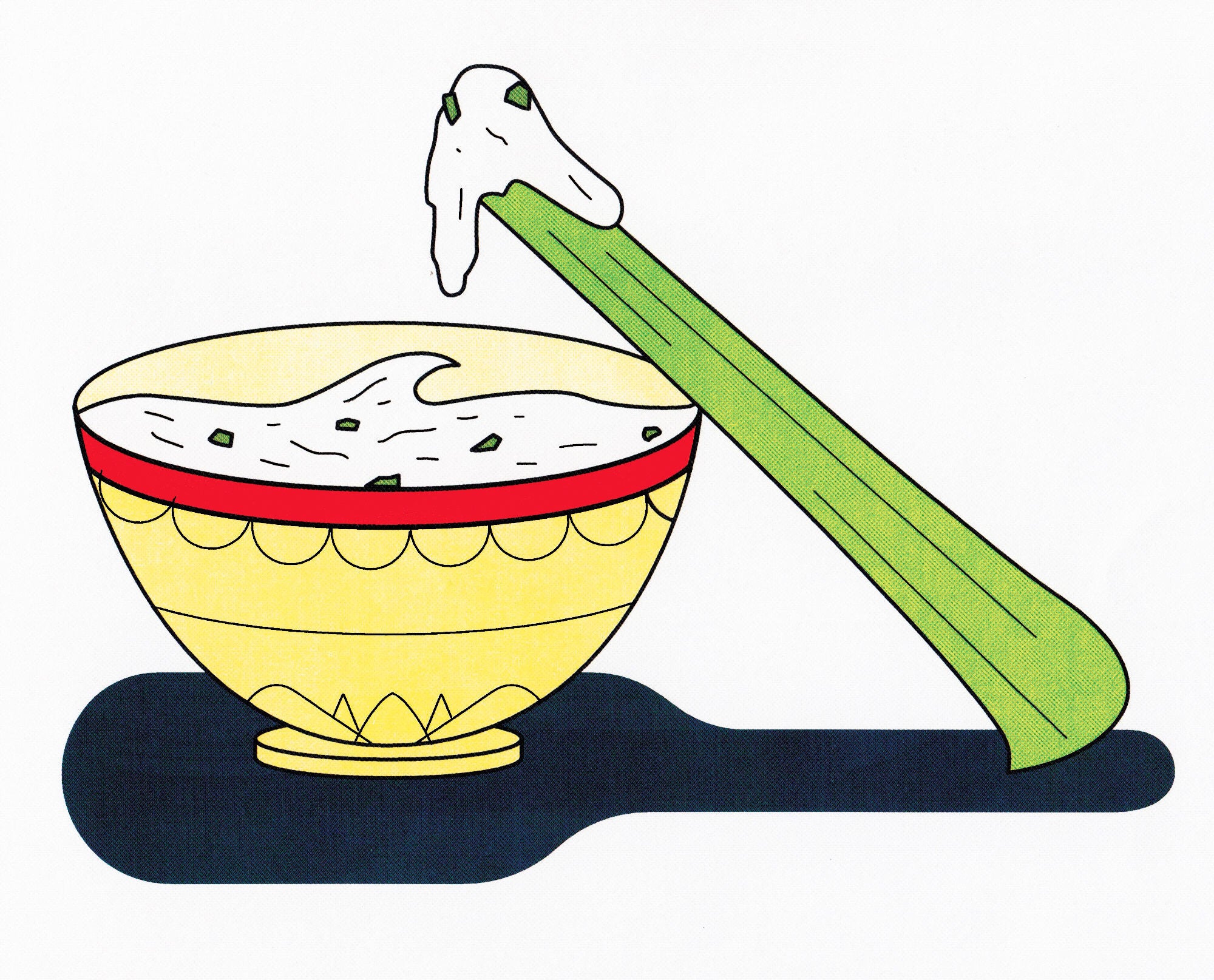

But celery was once a great luxury—one of the most fashionable foods to grace the table. The wealthy served it as the centerpiece of every dinner, while the average middle-class family reserved it for the conclusion of holiday meals. No Victorian household was complete without a glass celery vase—a tall, tulip-shaped bowl atop a pedestal—to prominently display the vegetable. Love it or loathe it, celery was once as fashionable as today’s dry-aged rib eye or avocado toast.

Native to the Mediterranean, celery cultivation began in the early 1800s in the cool, damp wetlands of East Anglia. It was fussy to grow and difficult to obtain—and this made it irresistible to the Victorian upper classes. Between the 1830s and the early 1900s, celery appeared as a standalone dish in countless cookbooks and housekeepers’ guides. It was served both braised and au naturel; it was presented au velouté (in a light gravy) and à la Espagniole (in a rich demi-glace). “Plain celery” as well as “dressed celery” (mayonnaise was de rigueur) were listed among the salads on a 1865 menu at the upscale Parker House Hotel in Boston. (Still operating today as Omni Parker House, the celery course is, tragically, no longer a thing.)

A little later, celery au gratin, the classy predecessor to today’s gooey celery-cheese casserole, was all the rage. At the same time, celery was considered a necessary accompaniment to canvasback duck, partridge, and other game birds. Celery was served in a first-class cabin dinner with roast squab, cress, and pâté de foie gras aboard the Titanic.

The height of popularity for celery vases was from the 1830s to the 1880s, but they were still being made (and ostensibly foisted onto hapless young brides) well into the 1910s. For awhile, the vases coexisted peacefully with their counterpart the celery dish, a long, narrow, boat-shaped bowl somewhat resembling an inverted butter dish—more effective for serving cooked celery that was too flaccid to stand upright in a vase.

The real reason for the vase’s demise, however, seems to have been its ubiquity. Famed nineteenth-century chef and cookbook author Jessup Whitehead lamented in The Steward’s Handbook and Guide to Party Catering (1889) that the celery vase had become, in the parlance of today, basic. “The fashions change as to the method of serving,” he wrote. “The tall celery glasses set upon the table form the handiest and handsomest medium, but having become so exceedingly common they are discarded at present at fashionable tables, and the celery is laid upon very long and narrow dishes.” The November 1891 issue of Ladies Home Journal echoed this sentiment. The magazine included concise directions on presenting celery in its “When and How to Serve Some Things” section (for planning Thanksgiving dinner), noting bluntly for the uninformed that “It is now served in long, flat glass dishes.”

Regardless of the mode of its service, Jessup Whitehead was adamant that celery was still “an article of necessity now for every good dinner in the winter and spring.” In England, celery had been long served raw as an accompaniment to a cheese course, as depicted in Charles Dickens’s novel The Life and Adventures of Martin Chuzzlewit (1843). One winter evening, one of the novel’s main characters is seen in a tavern enjoying “a most stupendous Wiltshire beer” with his celery and cheese. This evolved into the time-honored snack of celery sticks stuffed with cream cheese, first seen in cookbooks and ladies’ magazines in the early 1900s as a salad or as a cheese course to finish off a formal dinner.

James Beard noted in his American Cookery that “It was the nineteenth-century and early twentieth-century housewife and hostess who performed the marriage of the olive and celery,” but the duo had already been observed on hors d’oeuvres menus and relish trays in fancy restaurants and hotel dining rooms beginning around the 1880s.

Along with olives, celery was offered as a palate cleanser following the fish course or as a refresher after the soup course (both uses explain why celery is served with Buffalo wings today). This is likely where hostesses got the idea in the first place, not the other way around. Proper hostesses like my grandmother Laverne would never have deigned to put out a relish tray without celery and olives (black and stuffed) alongside radishes, dill and sweet pickles, scallions, and her Russian dressing.

As the celery craze was reaching its zenith in the 1870s, Dutch farmers who knew how to handle wetlands began growing the vegetable in the black, marshy soils of Kalamazoo, Michigan, which became known by the catchy name the Celery City. The streets were littered with hucksters peddling celery from street corners and train stations. As American cultivation improved, celery became an everyman’s item. By then, the British upper classes had moved on to French luxuries like truffles and oysters. Celery vases may have gone the way of the dodo, but one would be hard-pressed to find a premade veggie tray without a slot for celery. Like it or not, celery isn’t going anywhere.