Baumkuchen is a centuries-old staple of German weddings and Christmases, but it’s getting harder to find. Except one place.

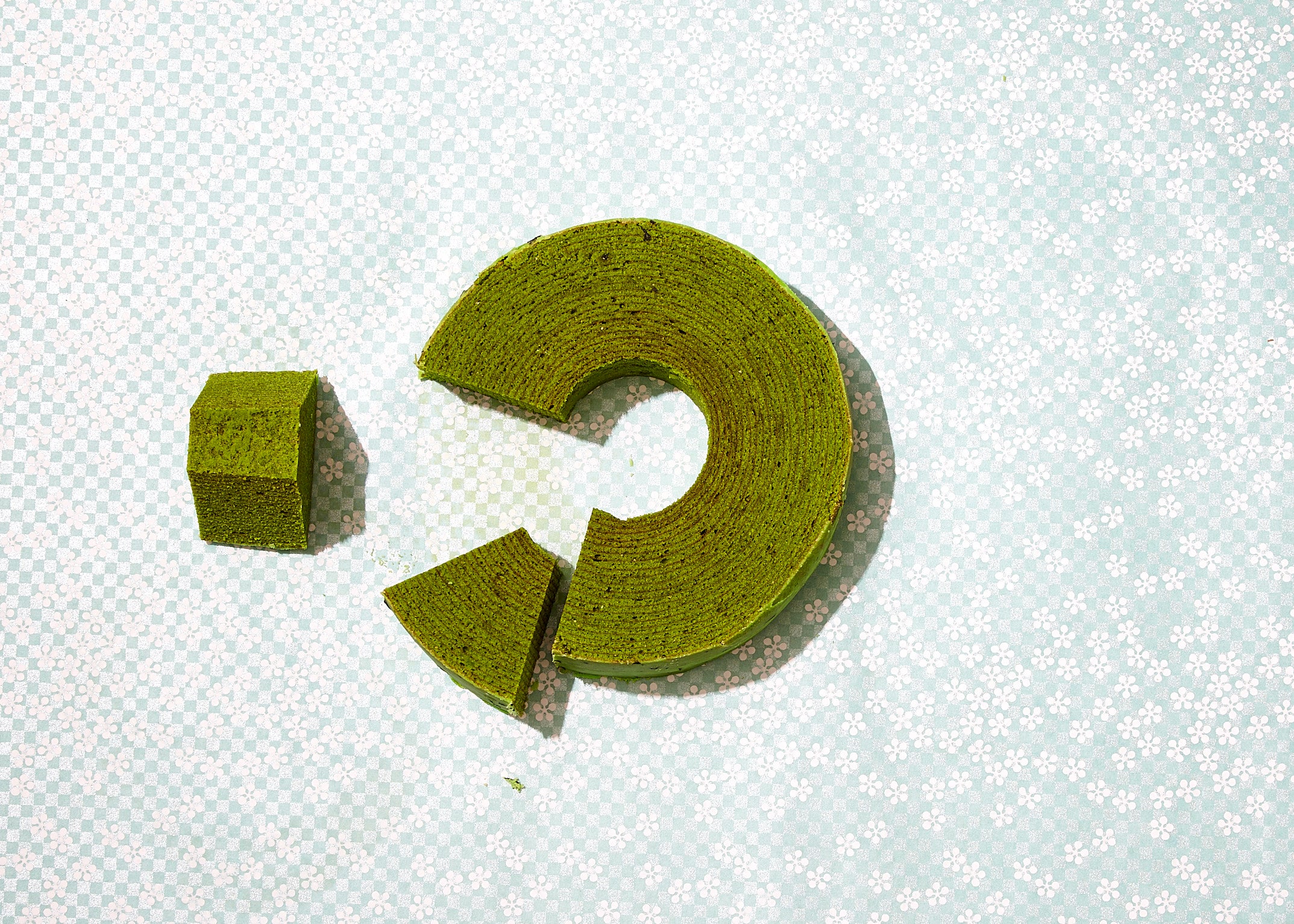

If you encountered a slice of baumkuchen (or “tree cake”) at a Japanese tea shop or at a German wedding and tried to guess how it was made, you’d be at a loss. The slices of cake are round, with thin concentric circles working their way out from a hole in the middle—like some sort of seamless amalgam of a crepe cake and a roll cake and a doughnut—or, to put it more simply, like a slice of a tree trunk, full of age rings.

Achieving this is a feat of unlikely cake engineering. The original method involves a spit turning over a fire. Thick batter is scooped, in heaping spoonfuls, directly onto the spit and spread across its length. As the batter drips and rotates, it creates craggy ridges, like the bark of a tree. When the batter turns golden brown, another scoop of batter is heaped on top, and the spinning continues. After 15 to 20 repetitions, the accumulating layers have formed rings that are imperfectly round and alternate between pale yellow and a toasty brown. The cake gets a glaze of warm apricot jam to seal in the moisture and prevent it from drying out, and then sometimes a crackly shell of chocolate or vanilla icing.

The cake has been a staple of German weddings and Christmas celebrations since the 1800s, but in the aftermath of World War I, baumkuchen found an unlikely second home when a German baker was interned in Japan and started to bake and sell cakes there. They were a runaway success, and today brands like Shimizu, Kihachi Sweets, and Muji manufacture baumkuchen in flavors like melon, mango, honey, matcha, and strawberry and ship them all over the world in individually wrapped slices.

While the Japanese version has a softer, lighter, spongier texture that translates to a longer shelf life, the German style is a little bit closer to a pound cake, so it’s ideal to eat it fresh—or at least within a few days of being fresh. But since baking the German style of baumkuchen requires unwieldy, custom-built ovens, getting into the business is a bit of a risk and a bit of a statement. Your options, more or less, are to find a defunct bakery whose owner is willing to part with their oven, or you can buy a new one for about $100,000.

In a 2009 piece in the The New Yorker, food writer Mimi Sheraton described baumkuchen as “one of the irresistible enticements of Yorkville, a food lover’s paradise of wurst, delicatessens, candy and bread shops, Bierstuben, and restaurants in the colorful Germantown that thrived along and around East Eighty-sixth Street, on the Upper East Side of Manhattan, until it began to fade in the nineteen-seventies.”

Since the 1970s, it has faded almost to a point of nonexistence, and so have old-school German bakeries around the country. Cafe Geiger, which Sheraton writes about fondly, has closed. Until four years ago, a holdout German bakery in Queens, Storks Bakery, made baumkuchen and shipped it to other places in the United States, but the bakery closed in 2013. In Denver, a bakery called Glaze made baumkuchen until closing up shop just a few months ago.

Paul Gauweiler, who has owned the Cake Box, in Huntington Beach, California, for 44 years, tells me there was a German bakery in San Francisco that made baumkuchen until about ten years ago too, but the cake is becoming as difficult to find as the specialized ovens it’s baked in. Gauweiler’s bakery makes baumkuchen in a machine that’s about 80 years old—a hand-down from a local culinary school after it closed—and ships the cakes everywhere in the country, as far away as Hawaii. Aside from his own business, and Lutz Café & Pastry Shop in Chicago, Gauweiler’s not aware of anyone else making and selling the cakes in the country.

While there is a whole hodgepodge of DIY methods for making it at home (ranging from complicated rolling techniques to jerry-rigged oven spits), one of the simplest comes from Luisa Weiss, the author of Classic German Baking. Weiss fires up the broiler and scoops a few spoonfuls of cake batter at a time into a regular round springform pan. Once each layer is lightly browned, she adds a new one, and when all the layers have been baked, she spreads the cake with warm apricot jam and an outer coating of melted chocolate. The finished cake isn’t exactly the same as the cylindrical confections of Berlin’s bakeries, but it might be as close as you’ll get without inheriting an 80-year-old oven.