The Great British Bake Off is often said to embody Britain’s national identity and culture. But the history of British baking has its roots in countries and cuisines thousands of miles away.

When The Great British Bake Off first hit U.K. screens in 2010, few expected it to become a cultural phenomenon. Yet after nearly a decade (and one highly publicized change of network), there really is no other word for it. The show’s agreeably low-stakes, warmly human formula has continued to resonate with viewers even after that network shift: It accounted for 7 of the U.K.’s top 10 most-watched TV episodes of 2015, and in 2017 it gave its new owner the network’s biggest ratings hit in 32 years.

To match the nation’s-sweetheart status of its judges and presenters, the show’s bakers have become celebrities in their own right, and then there’s what British newspapers like the Telegraph call the Bake Off effect—a retail phenomenon responsible for a threefold uptick in sales of home baking equipment between 2009 and 2014 (along with more recent spiralling increases).

In all of the many column inches devoted to the subject, one theme consistently emerges. This is a show, we are told, that embodies British values, British history, and British culture; that proudly upholds them, regardless of whatever assails the world at large. In a 2016 piece for The Atlantic (called, with no trace of hyperbole, “The Great British Break-up”), Sophie Gilbert fretted that the switch to Channel 4—and the resulting absence of the best-loved personalities from the BBC run—might undermine the panacea-like qualities of the show, its consoling presence as “a reminder that, no matter how bad things get, the fabric of the nation is built upon cups of tea and feather-light sponges.” A year later, Gilbert was delighted to note that the new Bake Off nevertheless remained “a green and pleasant island in stormy waters.”

The Eccles Cake at St. John restaurant in London (photo by Stefan Johnson)

These metaphors paint Britain as an island-nation sanctuary, its foundation built on native flour, butter, sugar, and eggs. But few—if any—writers on the subject have been willing to consider a curious irony: that British baking really isn’t very British at all. Like fish and chips, that other British culinary icon, a cup of tea and an assortment of baked goods—whether biscuits, cakes, pies, or tarts—together represent an almost sacrosanct signifier of national identity. Yet just as telling the true story of fish and chips involves acknowledging the ubiquity of fried-fish preparations in countries around the world, as well as the role of Jewish immigrants in bringing the dish to British soil, the history of British baking has its roots in countries and cuisines thousands of miles away.

Our baked foods feature a whole host of nonnative ingredients, especially fruit and spices. A common misconception is that British food is cautiously flavored, but the doughs of teatime breads like teacakes, Lardy cake, and hot cross buns are commonly enriched with raisins, sultanas, currants, and citrus peel. We do not often think to notice these exotica because our peculiarly parochial naming conventions seem purpose-built to obscure them: we talk of Bakewell pudding, when its ground almonds make it as much a product of the Mediterranean or Middle East as the Midlands; with their currants, allspice, and nutmeg, Eccles cakes—small stuffed pastries named for a single town in Lancashire—possess a footprint that spans Ionian and Caribbean islands as well as British ones. And then there is the Chelsea bun, perhaps the ultimate culinary product of our globetrotting and acquisitive national spirit: a headily aromatic and well-traveled confection of lemon peel, cinnamon (and/or other spice), currants, and brown sugar.

The history of British baking, then, is really the history of Britain’s interactions with the rest of the world. It starts with the foods and flavors imposed by visiting conquerors, the Romans and Normans leaving a lasting influence that includes grapes and the French word for them, raisin. In the Middle Ages, narrowly defined notions of nationhood were of less importance than the more horizontal, culturally promiscuous structure of court society; this led to the free circulation of techniques and ingredients—especially dried citrus, newly available and transportable from the Middle East—across much of Western Europe (it also helps explain, for example, why practically every country in that region has a recipe using ginger, the most common spice of the day).

Hot cross buns

The 18th century saw Britain taking violent control of the spice routes; this, along with the development of faster ships, meant vast quantities of (relatively) fresh spices flooded the domestic market, driving down prices and making nutmeg and mace accessible to home cooks for the first time. The booming empire meant more sugar and the evolution of tea from a rarity to a staple, which in turn fueled demand for more baked goods to consume with it.

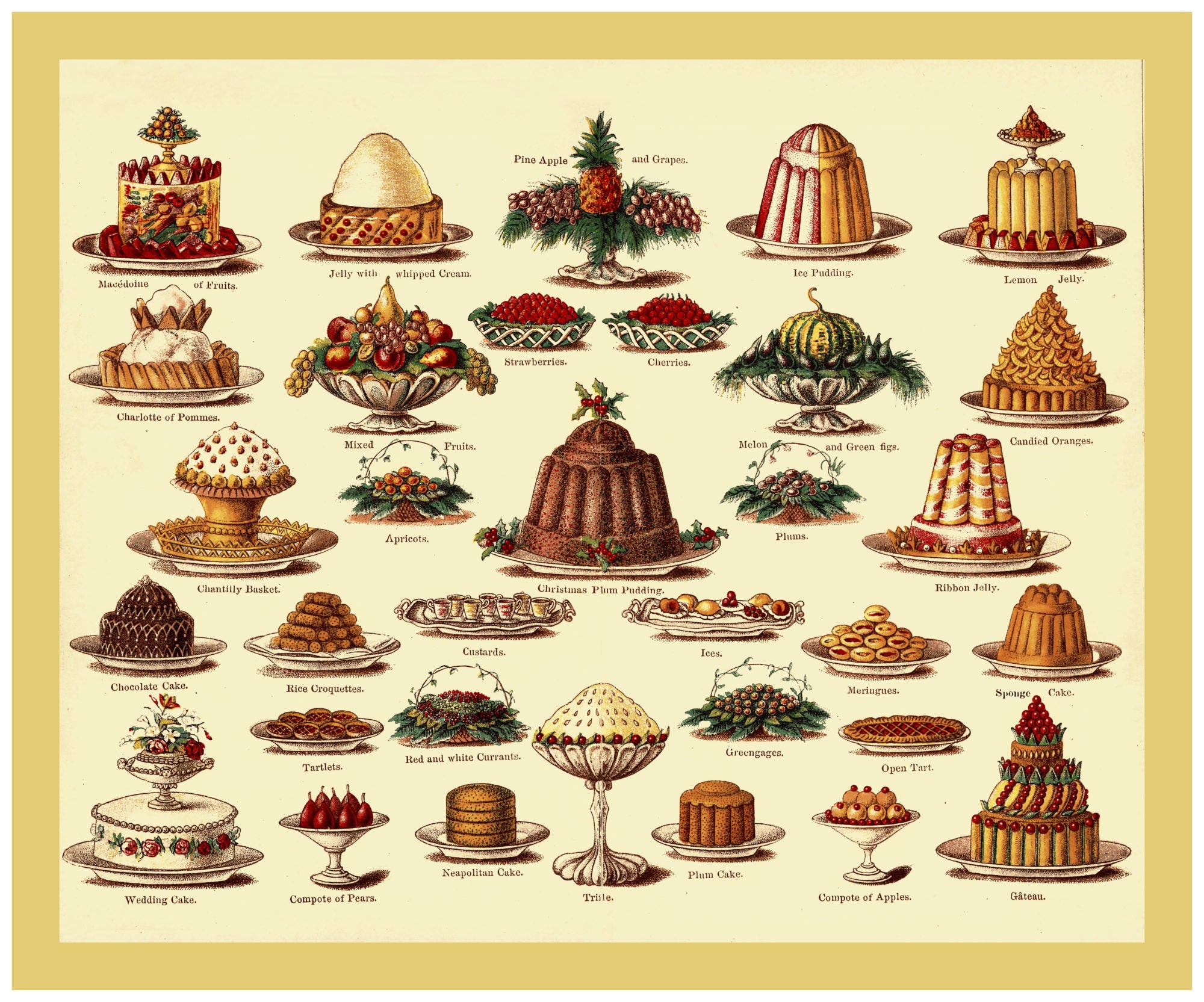

The onset of the Industrial Revolution in the mid-18th century brought ever-improving milling technology over the following decades and resulted in the introduction of cheap white flour and baking powder to the domestic cook. As a consequence, the Victorian age saw the first true British baking boom, one that was subsequently derailed almost totally by two world wars, the second in particular: Fourteen years of rationing had a disastrous effect on both the tastes and cooking aptitude of a whole generation.

The propaganda associated with World War II introduced a whole series of archetypes for Britishness; the war itself was also essential in defining “us” as Brits, in the sense of affording us a “them” to define ourselves in opposition to. And it’s hard not to see the booming popularity of shows like The Great British Bake Off (and spin-offs like The Great British Sewing Bee and Pottery Throwdown) as a function of a similar cultural moment.

When I spoke to the writer Ruby Tandoh (a finalist in the 2013 season of Bake Off) about the success of this peculiarly nostalgic genre of programming, she didn’t find its emergence surprising: “It’s not a coincidence that this has happened as we’re being forced to look outward more and more, in an uncertain world,” she told me. “Our identity is being brought into question, so we’re looking back to history to help shore it up.”

The moment in history invoked by Bake Off is a curious one, equal parts idyllic pre-Industrial village fête and V.E. Day bunting parade. Writing for the Guardian on the subject, cultural critic Charlotte Higgins described this “utopian” version of Britain as both “unspecified” and “ungraspable”—citing similar invocations of national identity by George Orwell and Prime Minister John Major, both desperately “asserting the strength of a national culture at times when Britishness […] was felt to be under threat from outside dangers.”

While The Great British Bake Off has done more than most television programs to showcase the nation’s demographic diversity, it is also more complicit than many in endorsing and sustaining this weird, warped version of our national history.

As an island nation, we are acutely aware of threats from across the water, and acutely receptive to distractions from them. In 2010, when Bake Off launched, the economy was on its knees as the global financial crisis took its toll; a low-jeopardy, frothily escapist TV show could not have chosen a better time to air. These days, the cozy fictional version of Britain that it presents surely feels more alluring than ever before, as the country teeters on the verge of formalizing its departure from the European Union.

Both The Great British Bake Off and Brexit subsist on the unwillingness to face uncomfortable truths. The myth of both is the myth of self-sufficiency, of a return to the good old days. Except, of course, there are no good old days of self-sufficiency. We have collaborated, welcomed, befriended, swindled, traded, enslaved, and exploited our way to where we are today, but at every stage we would have been nothing without other nations. We are still a long way from acknowledging the totality of our dependency on the world (and, for that matter, the wrongs we have done it in the name of empire and national sovereignty); somehow, we continue to persuade ourselves that we are the captains of our fate.

And while The Great British Bake Off has done more than most television programs to showcase the nation’s demographic diversity, it is also more complicit than many in endorsing and sustaining this weird, warped version of our national history. The show wants you to believe that a Chelsea bun and a cup of tea represent Britain at its best and most quintessential; the truth, though, is that there are few better symbols of our peculiar and sustained hunger for self-delusion.

With thanks to the food historian Dr. Annie Gray, who provided valuable context for this piece.