We found the cookbook author in Hawaii, still writing and tossing the occasional pizza.

Ken Forkish, the author of the 2012 best-selling bread and pizza cookbook Flour Water Salt Yeast, is one of a handful of professional bakers who transformed the global home baking scene with a single recipe: a no-knead style that put real bread—crusty, crackly, dense, and flavorful—within reach of home cooks. But in Portland, Oregon, where he ran a pizzeria and one of the country’s very best bakeries (according to nearly everyone who rates them), he was also a linchpin of the city’s exciting and often influential food scene. For the past two decades, many people knew his scrupulously made breads, pizzas, and pastries by name, including the slow-fermented rounds of Overnight Country Blonde, or the Handmade, a perfectly pillowy cheese pizza where every single element is made from scratch.

So it was a very big deal when the news broke earlier this year that Forkish had abruptly sold both businesses and moved very far away to his “happy place”: Lanai City, Hawaii. A few weeks later, he told the Oregonian there was “zero” chance he’d ever open another bakery, where most of the labor is spent managing people, he says, rather than making dough.

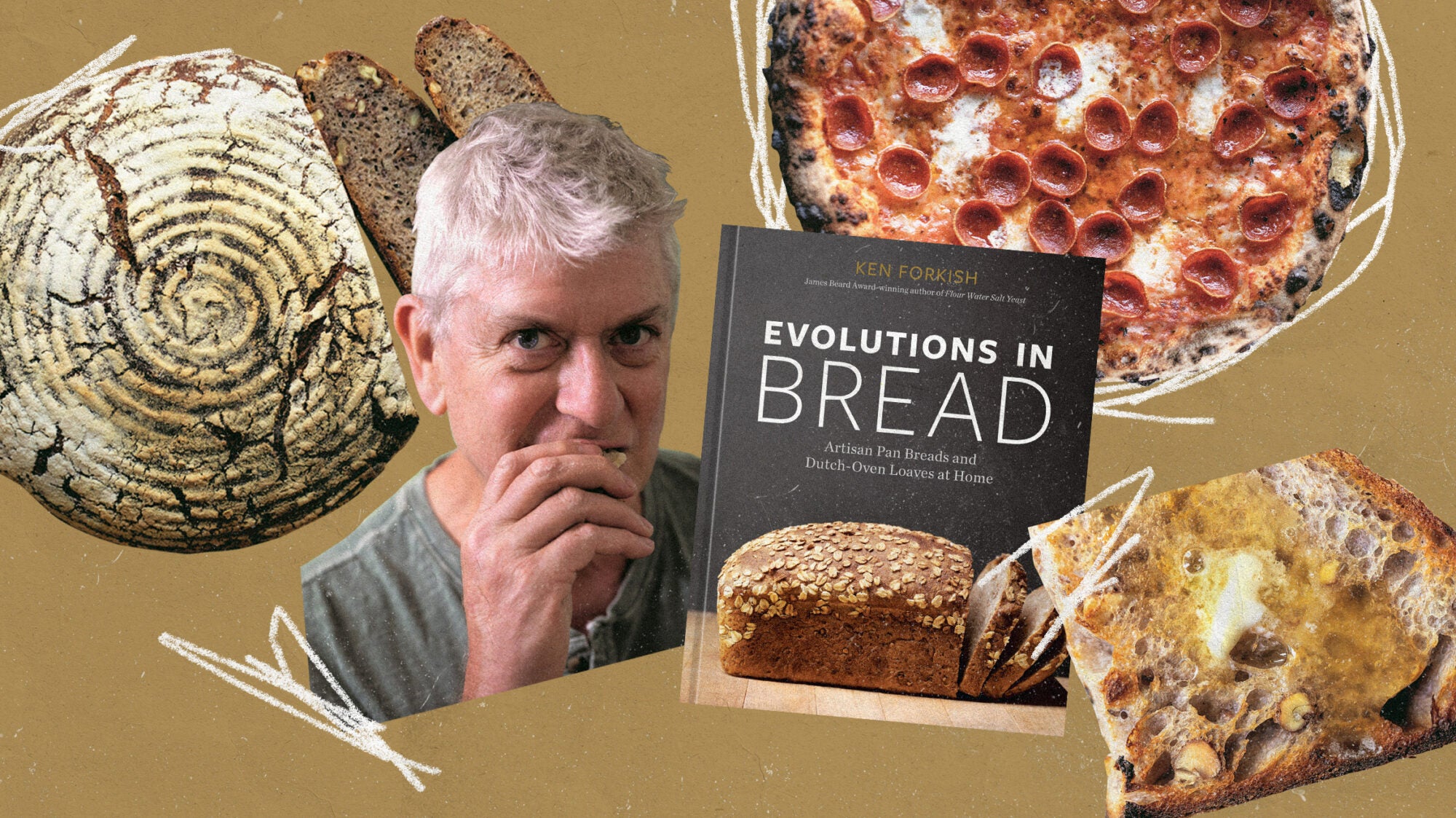

Forkish fans looking for a big life (and baking) update from the man are in luck, though, because his new book, Evolutions in Bread: Artisan Pan Breads and Dutch-Oven Loaves at Home arrives this fall. I talked to Forkish in August about how this book is different from his blockbuster first book and about the ways his new recipes work better for home cooks, a group that now includes Forkish.

He also told me that, even though there’s still no chance of a bakery, he continues to bake for paying customers. If you find yourself at the Four Seasons Resort Lanai on just the right evening, Forkish will make you a pizza during happy hour.

“That’s the limit—twice a month for a couple of hours on a Thursday,” says Forkish. “It keeps me engaged in a pretty good way.”

Is Hawaii a bread place? Do people get into to it like they do everywhere else?

There’s probably not many people who bake bread at home, because it makes your house hot, and it’s already hot, and the cost of air-conditioning is really high. Electricity is more expensive here than anywhere else in the country.

This is a perfect segue to something I wanted to ask you about. You’re totally a home baker now, and your new book is really in that domain, right?

I think all my books have been in that area.

Yes, but this one is about loaf pans and sliced breads for sandwiches. Homey.

I’m trying to improve breads that people have typically made at home but not bought at a store, and I’m also throwing in some options, like a multigrain bread, that people don’t make at home. I would rather they make their own, because—have you ever looked at the ingredient list on a multigrain bread?

Yes, but pretend I haven’t! Tell me what I would be shocked by.

Well, vital wheat gluten. Why the fuck do you want to add more gluten to your bread, if you’re using good flour? Industrial baking. [Vital wheat gluten] will support a fast rise, and it’ll support all this stuff that you put into it and still have loft. That’s the only reason for doing it—for physical structure, not because it makes it taste good. In return, it also puts more of a digestive load on your belly. Why would you want that? You can make a really good multigrain bread at home using my recipe. I like it a lot. I’ve got heirloom barley, oats, and buckwheat groats in it.

The vital wheat gluten probably isn’t even the worst thing on the label, either.

To me, it is, just because I know why they use it. You’re not doing someone’s belly a favor, putting more gluten into bread that doesn’t need it. The gluten does take a lot of work to break down, and that’s one of the reasons why long-fermented doughs are good for you, because enzymes in the dough break down a lot of that gluten for you.

Why the fuck do you want to add more gluten to your bread, if you’re using good flour?

Which is why people feel so bad when they eat bad bread?

It’s a correlation, maybe not cause and effect. You were talking about homey breads. I think that Dutch-oven breads have been pretty well covered in cookbooks, but I haven’t found any other cookbooks that take a really high-quality approach to pan breads, and that’s what I wanted to do with this one.

One of the other things you said wanted to do, which seems very home-cook positive to me, was reduce the amount of flour that was required to build your breads.

During the pandemic, when people were making sourdough because you couldn’t buy yeast, I was feeling really bad about the amount of flour that I put in my first book. That was never, for me, a design objective when I wrote Flour Water Salt Yeast. I was so concerned about having a recipe that would work. I knew, with a little bit more fuel for the sourdough, that it would consistently perform.

But 500 grams of flour at every feeding was just too much. It was standard at the time, though. I was looking at other books, and everybody was doing that amount of flour. Even in Modernist Bread, it was using a lot of flour, like I did in my first book. That became a design objective in my new book, Evolutions in Bread, to do a flour-efficient sourdough, and I think I did that pretty well.

On behalf of all fancy-flour-buying home bakers, I just want to thank you very much.

Absolutely!