César Ritz and Auguste Escoffier built a legacy around luxury hospitality that long outlived their dubious management tactics.

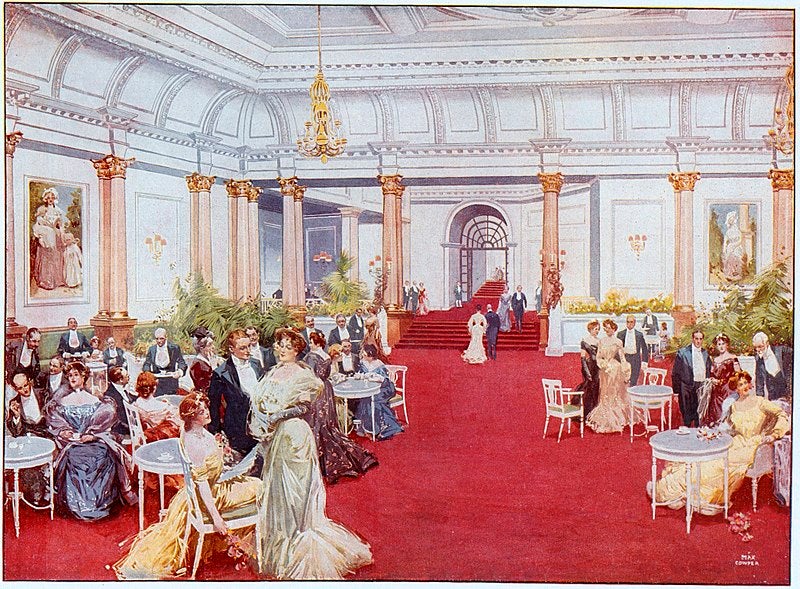

In 1895, two friends, Woolf Joel and Frank Gardner, who’d made their fortunes in mining won an exceptionally large amount of money playing roulette in Monte Carlo. They’d bet on red and won on 12 consecutive spins, the final ball landing on the number 9. A week later, with their newfound wealth burning a hole in their pockets, they hosted a dinner for 30 friends at London’s most opulent hotel: the Savoy. The Savoy’s celebrated hotelier-chef duo, César Ritz and Auguste Escoffier, were famous for staging dinners with extravagant, theatrical flair, and this was no exception. A large private room was draped in sumptuous red fabrics. Lights shone through red shades. Table settings were red with immense bouquets of red geraniums at the center. Red menus were printed with a roulette wheel on one side and the figure 9 on the other. Waiters dressed in red ties and gloves, and shirts with red buttons, and served dishes of consommé of red partridge, foie gras in paprika gelée, and lamb with red bean puree. London’s Daily Mail newspaper reported the dinner cost £10 per person, or $1,800 each by today’s standards.

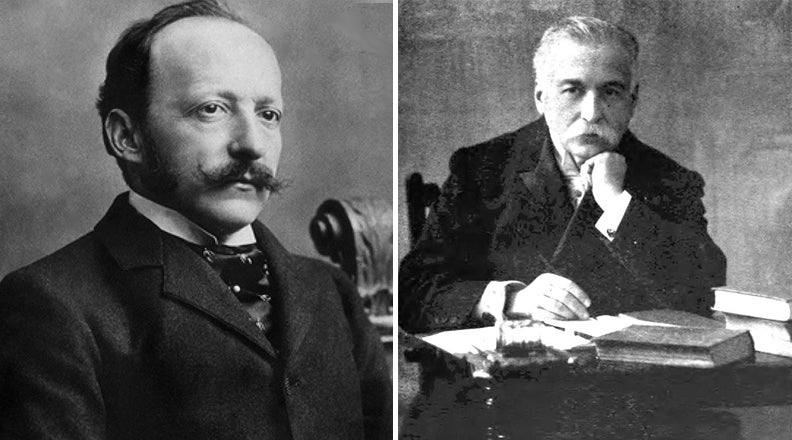

In his newly released historical narrative Ritz and Escoffier, Luke Barr tells the story of the celebrated hotelier and chef. “I was looking to write about a seminal chef and immediately thought of Escoffier,” he says. “When I began researching, I discovered he’d been César Ritz’s business partner.” With the Savoy hotel as his backdrop, Barr focuses on a 10-year period beginning in 1890 and lays out the duo’s illustrious rise and the scandal that sent them packing. It’s a timeless and cautionary tale of power, privilege, and failure. “They were modern people, two working-class men who came to reign over the world of luxury hotels and restaurants,” he says.

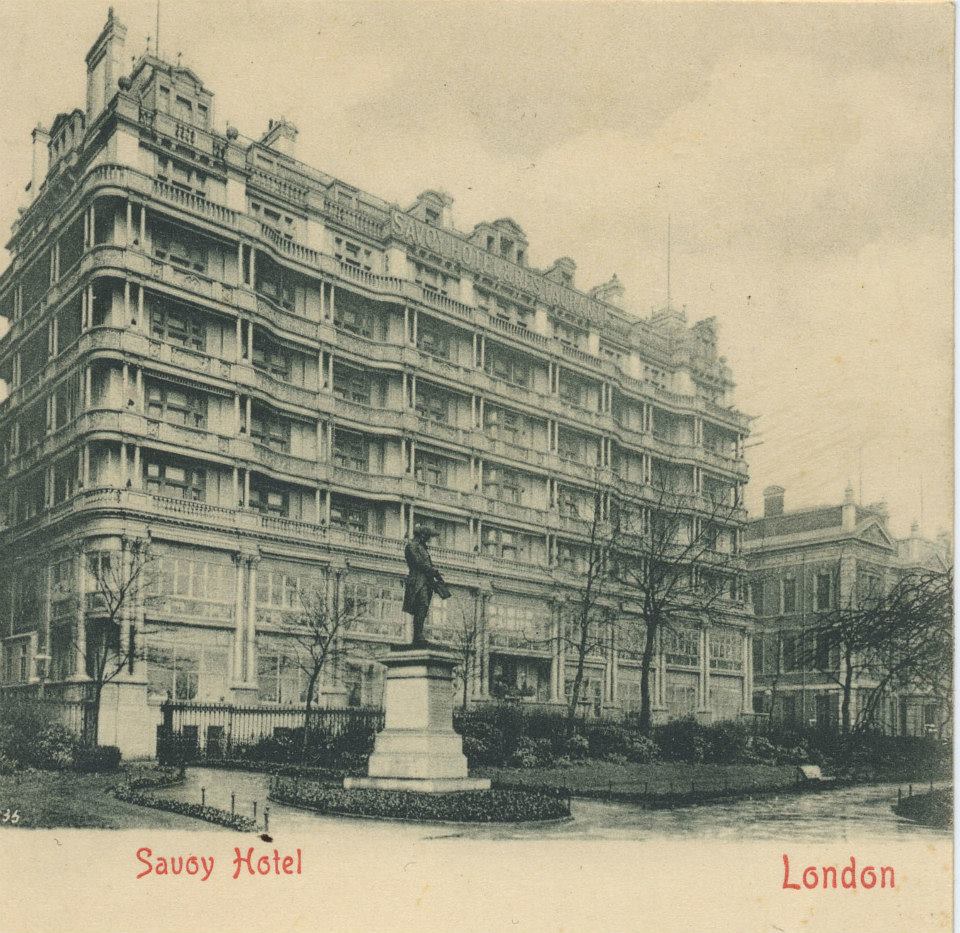

Situated at the center of cosmopolitan London, the Savoy hotel was a place where aristocrats, nouveau riche industrialists, wealthy American travelers, bohemian intellectuals, and celebrated actors mingled. It was an aristocratic fantasy fashioned after American establishments like the Palace Hotel in San Francisco with its modern amenities of en suite bathrooms and large elevators. There was no hotel like it in Europe. The Savoy was representative of a new era of style and luxury.

César Ritz and Auguste Escoffier

Among the architects of this move toward modernity were Ritz and Escoffier. Escoffier had been the son of a blacksmith from the South of France, and Ritz came from a poor family in rural Switzerland. They had built parallel careers working in luxury seasonal hotels in places like Germany’s spa town, Baden-Baden, and France’s rural Provence, and the pair struck a business alliance based on mutual respect and complementary skills.

In 1889, Richard D’Oyly Carte, a wealthy theater owner famous for producing Gilbert and Sullivan’s operas, wooed Ritz and Escoffier to the Savoy hotel in London. As the owner, D’Oyly Carte went to extraordinary lengths to secure their employment. “They were paid a preposterous sum of money,” says Barr. According to British food writer Paul Levy, their salaries were the equivalent of millions, a sum to rival the top modern celebrity chefs and hoteliers.

The Savoy Hotel in 1900

For six years, the hotel’s business boomed. But in 1897, the Savoy’s profits fell by an astonishing 40 percent. For the first time, Escoffier recorded a loss in kitchen revenue. At first, the hotel chalked this extravagant use of money up to just the cost of doing business. (“The best is not too good” was Ritz’s maxim.)

But the alarming financial situation triggered an audit that turned up evidence of illegal use of hotel money. Wine and spirits comped to guests and consumed by staff accounted for the equivalent of more than $1,000,000, a figure that far exceeded the normal parameters of generous hospitality. Compounding this was the revelation that the duo was using the Savoy dining room to woo clients and investors for other hotel projects the men were planning, including a soon-to-be competitor in London, the Carlton.

A 1907 painting of a dinner at the Savoy, by Max Cowper

In February 1898, news of Ritz and Escoffier’s dismissal made the London papers. D’Oyly Carte told the pair they had forgotten “they were servants and assumed the attitude of masters, and proprietors.” The Savoy hired police protection out of concern that employees faithful to the pair would riot. Susan Scott, the hotel’s archivist, refers to the period as the “great divide,” emphasizing the split in loyalties among staff. “D’Oyly Carte and shareholders were mortified and considered the scandal a huge embarrassment,” she says. “They agreed to deal with it quietly.” And for almost 100 years the Savoy was successful at keeping the secret.

But in 1984 a hotel intern stumbled on confessions of embezzling signed by Ritz and Escoffier in the Savoy archives and sent them to Paul Levy, who was the food and wine editor at the London Observer at the time. He discovered the 5 percent kickback scheme Escoffier had with Savoy suppliers, which netted the chef the 19th century equivalent of nearly $2,250,000. Levy took particular issue with Escoffier, a man whom many considered the patron saint of chefs, and called Escoffier “a blue-collar hero, white-collar crook.”

But even the resurfacing of these crimes 100 years after the fact hasn’t tarnished the names Ritz and Escoffier, which are still synonymous with extraordinary lavishness. Within months of being sacked from the Savoy, the pair opened the Carlton in London and the Ritz Paris, which still exists today. Escoffier wrote Le Guide Culinaire, which has secured his reputation with chefs to this day. The duo created a formula for luxury so outsized and ostentatious that it outlived any scandal they left in their wake. “Kings and princes will be jealous of you,” Henry Higgins, chairman of the Ritz Paris, famously prophesied to Ritz. “You are going to teach the world how to live.”