In his brief but influential television career, Graham Kerr taught people to cook heartily, with lots of clarified butter, and laugh even harder.

If midcentury television food celebrities were a family, James Beard was the aggressive firstborn who paved the way, bossy and prone to petty jealousy. Julia Child was the diplomatic middle child, a people-pleaser and peace-keeper. And Graham Kerr, the baby of the family, was the risk-taker who would do just about anything for a laugh.

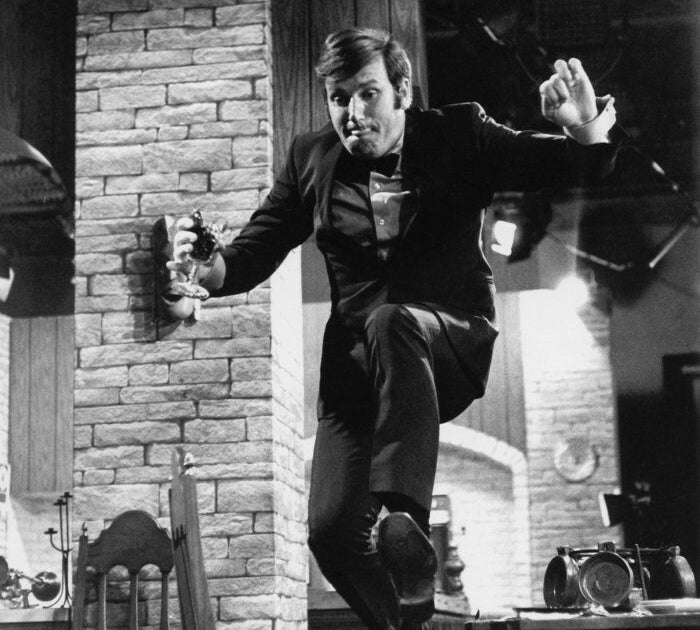

Leaping over chairs with wineglass in hand, joking bawdily about Amsterdam’s red-light district or the anatomies shared by a chicken and a woman, the Galloping Gourmet lived up to his moniker as the “high priest of hedonism.” Kerr’s onscreen humor was heavy-handed and coarsely suggestive (holding button mushrooms up to his nipples, for example), but being tall and rakishly handsome (with a British accent to boot) likely excused much of his cheek, if it didn’t enhance it.

His show, a 30-minute cooking program featuring footage of his global travels and instructions for cooking dishes from his destinations—peppered with his trademark droll banter—aired nationally on CBS at the sudsy timeslot of 1 p.m. weekdays to a predominantly female live studio audience. He was a good-looking amalgam of Peter Sellers and Guy Fieri, he was jet set in the golden age of air travel, and his show was a goddamn sensation. In 1971, after two years of recording hundreds of episodes at a breakneck pace, the show abruptly ended when a 16-wheeler speeding down the foggy curves of Highway 101 smashed into the Kerrs’ Winnebago from behind, dislocating Kerr’s spine. The starstruck nurses in the hospital harangued Kerr for autographs, leading his wife to declare the show officially over.

Today Graham Kerr, a youthful and sterling 83, lives in a tidy, modest house in Mt. Vernon, Washington, a rural paradise 60 miles north of Seattle. His custom-built home is dwarfed by his neighbors’ mansions, a point of pride for Kerr. “It’s only 1,400 square feet,” he brags. The home, dubbed Nonsuch Cottage, is as full of character as its owner, with kooky nautical motifs, an accent wall papered in a quiet forest scene, a groovy modular dinette set. His late wife, Treena, laughs in photos throughout the house, and picture windows look out over the tranquil Skagit Valley.

Kerr at his home in Mt. Vernon, Washington

While we chat over the course of a cozy fall afternoon, Kerr prepares an unexpected collation of sensible foods, a time capsule of 1980s gourmet cuisine for the health-conscious: salmon patties topped with timbales of delicata squash from his garden that he’d neatly hollowed and filled with scrambled egg cut with Southwest-flavored Egg Beaters and capped with a half slice of melted pepper jack. (This flavor of Egg Beater is evidently his invention; he tells me he’d asked ConAgra a while back to improve the flavor of their egg substitute, and this was what came of it.)

This is a far cry from the televised version of Kerr, the one who moans ecstatically at a two-inch-thick Florentine steak, or dives into a soup bowl of crème brûlée he’s just made, crying, “Oh! it’s just a dream! it’s divine!” On air he made a classic English treacle tart, smoked eels on toast from Holland, and Jamaican rum–soaked pork pot roast, managing to squeeze about a cup of clarified butter into everything he did. After pendulous swings from lavish abundance in the groovy ’60s to ascetic self-denial following his wife’s stroke and heart attack in the 1980s (finding evangelical Christianity in between), the decades of moderation look good on the man. Kerr seems as vibrant as ever, and he hasn’t shrunk an inch of his nearly six and a half feet in height. “Keep this up,” I jokingly warn him, “and you might live another 20 years.” He politely chuckles. But the thought clearly worries him. This day is his anniversary; he and Treena would have celebrated their 60th had she not passed away a few days shy of the date in 2015. His autobiography, published the same year, is dedicated to her and includes a touching (if somewhat morbid) promise that he’s on his way to join her.

On air, part of his shtick was laughing off his frequent cooking gaffs, interspersed with moments of exhibition, like chatting up his audience while chopping vegetables, making a point to cavalierly keep his eyes anywhere but his hands. Like Guy Fieri, Kerr’s larger-than-life personality was adored by a wide audience and held a populist appeal, but his colleagues—a clubby group mostly living in the cities of the Northeast—were less than charmed. Much of the food writer “It” clique openly derided Kerr’s work as schlock. Their reaction was a collective eye roll at his mockery of their refined discipline; his was a light entertainment for the lay user. Food writer Michael Field dubbed him “the Liberace of the food world.” New York Times television critic Jack Gould bemoaned Kerr’s “cultivation of a suffocating demeanor of haughty cuteness.”

Although Kerr’s unique combo of boisterous humor and debonair swagger did much to encourage men to enter the kitchen, James Beard found Kerr obnoxious and took sport in throwing shade at any opportunity. He called Julia Child on the phone to lambast Kerr after meeting him for the first time. Beard also went on the record with LIFE magazine in 1969, saying, “I don’t think he’s a great food authority, and he hasn’t done much to increase the cause of good food.” (This was particularly rich, considering Beard—who long took money from food companies to produce what we now call sponsored content—began his culinary profession as a hustle for cash when, by his late 30s, his acting career had still failed to take off.)

The ever-magnanimous Julia Child appears to have been the only food celebrity with whom Kerr got along well, and the two remained friends over the years. “I could never jump over a chair!” he says she once told him (doing a spot-on impression of her), while acknowledging with self-deprecation that the only reason his show could compete with hers was his flair for zany acrobatics. Although Child found him “just charming” and said he had a good personality for TV, she later playfully mocked his health-crazed philosophical flip. “Graham is nonalcoholic and ten percent or less fat, which is absolutely what I am NOT,” she said during a cooking demo with Kerr in 1996.

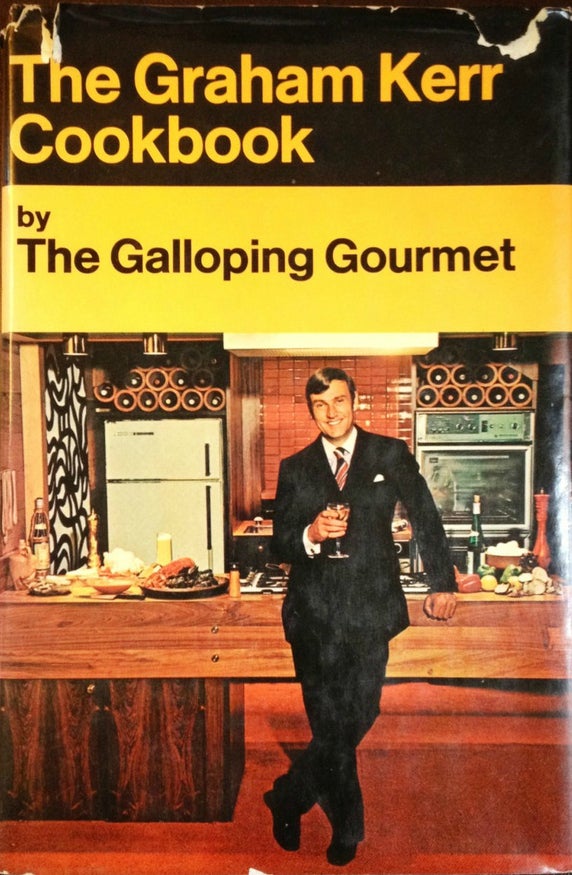

Kerr’s first cookbook, The Graham Kerr Cookbook, is as cookable today as when it launched in Australia in 1966 (the American edition was in the works before the show aired). “He had a feverish attention to detail,” cookbook author Matt Lee tells me over the phone. “His zeal for the scientific method carries through with the rigor applied to his recipes, making [the book] far ahead of its time.” This is why Lee and his brother Ted have worked with Kerr on the reissue of Kerr’s cookbook (due out in April 2018). They bring back those features from the original Australian edition lost in the American one; they updated the recipes to reflect modern ingredients availability, and added archival color images from the show’s original photographer Bob Peterson. And the new issue includes Kerr’s handwritten commentary on the recipes.

The Galloping Gourmet Cookbook will be reissued in 2018.

Nowadays, Kerr eschews fine wines and cheeses for the ephemeral delights of a Yakima peach in August or the local one-day strawberries (“We grow them here, and they’re only good for one day,” he softly gushes). He believes in putting “nourishment before delight” and dismisses comfort food as a false idol, saying that it’s our memories, not the foods served while we’re making them, that are important.

Not surprisingly given his age, Kerr seems preoccupied with his legacy, talking openly about reducing consumption, philanthropy, and faith. Sounding a bit like a hippie sage, he implores us to “search for a way (to) get beyond our own immediate self-interest” and live and behave more altruistically. “And if we could do that in an interesting way,” he says, “so that it flexes and doesn’t become self-righteous, then I think we could actually see a mechanism of reducing our own personal consumption in order to have something to share with somebody else.” He acknowledges that it’s all a bit pie-in-the-sky, but he hopes for it nonetheless.

Now in his twilight, Graham Kerr has entered a period of what he calls recalculation. After all the U-turns his culinary viewpoint has taken, I ask him if he’s all out of swings. With his eyes sparkling, he tells me that he’s working on another book. It’s about making changes.