Potstickers, Cornbread, and Spam Musubi

For cookbook author Cynthia Chen McTernan, there’s no such thing as an unconventional pairing.

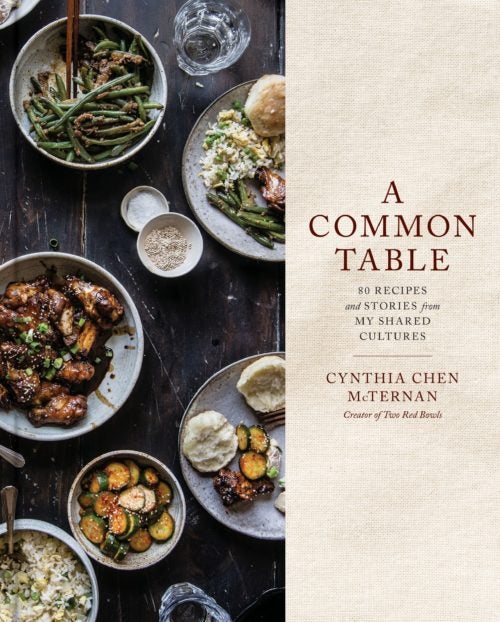

It’s not uncommon to find kimchi chicken quesadillas, collard green wontons, and Shanghainese red cooked pork on Cynthia Chen McTernan’s dinner table. For the popular blogger behind Two Red Bowls, these disparate foods embody the multiculturalism of her family, taking influence from her own Chinese-American upbringing in Greenville, South Carolina, and her Hawaii-born husband’s Korean-Irish background. Her new cookbook, A Common Table, serves as a representation of the many Venn diagrams that make up her home cooking. It’s not fully Chinese, not quite Southern, nor entirely Korean, but rather the embodiment of a multihyphenate.

“I guess Asian-American is the best way to describe it, because it’s a little bit of everything,” McTernan tells me. But in her mind, it’s less about clinging to that label. “When people ask, I just tell them it’s just things that I like to eat. Everything in this book is a reflection of my favorite foods, which are all influenced by my background.”

As she began to conceptualize the cookbook, McTernan instantly drew parallels across recipes. “There are flat Southern chicken and dumplings [sometimes called slicks], which I realized are really similar to Korean sujebi,” she says, referring to the dough flakes found bobbing in chicken broth at traditional Korean restaurants. The recipes utilize the same hand-tearing technique and all-purpose dumpling dough—it’s as simple as combining flour, salt, and boiling water. And that same dough recipe works for potstickers, too.

Throughout the book, McTernan employs classic techniques that appear in every cuisine in varying iterations. With a hunk of lamb shank, she chooses to make a ragù to go with eggy pappardelle pasta—but also pays homage to her mother’s version, which is braised with radishes and ginger root and served over cellophane noodles. At its core, the bare bones of the process remain the same, and it’s just a matter of a few tweaks, like swapping out red wine for Shaoxing wine, that make the difference.

But while her recipes are deeply personal and particularly rooted in her own family—like her Shanghainese great-grandmother’s lion’s-head meatballs, or spam musubi, which represents the beginning of her relationship with her husband—they speak to how home-cooking styles continue to evolve. Upholding tradition while weaving in varied influences creates a wholly new identity, which flourishes in its own fluidity and lack of adherence to one category.

“If the traditional dishes in this book represent where we come from—my family, my husband’s family, and the traditions that were passed down to us,” the introduction reads, “I like to think of these ‘new’ dishes as the quirky emblem of where we are going.”

Ingredients

- 6 tablespoons unsalted butter, melted, plus more to grease the skillet and for serving (optional)

- 1 cup yellow cornmeal

- 1 cup all-purpose flour

- ¼ cups toasted sesame seeds, plus more for garnish

- ¼ cups sugar

- 1 teaspoon baking powder

- ½ teaspoons baking soda

- 1 teaspoon salt

- ¾ cups whole milk

- ¾ cups full-fat Greek yogurt

- 2 large eggs

- 5 tablespoons honey, divided

- 1 tablespoon sesame oil

Cornbread is a subject of vigorous debate in the South, and whether to add sugar is especially particularly divisive. Given that my family only recently immigrated to the South, the reason I love sugar in my cornbread isn’t because it’s the way my family has always done it, but simply because it’s what I like.

As a result of having little tradition to anchor me to how cornbread “should” be, but loving it all the same, I’ve slowly come to a version that is unabashedly untraditional, sidestepping all debates about sugar and landing on a quirky recipe that has just a bit of Eastern influence. It is plenty sweet, of course, but also subtly smoky and nutty from sesame seeds. You can brush more sesame oil on after baking to bring out the flavor even more strongly, or you can serve it with butter and a bit of honey—this is no traditional cornbread, after all, so it’s up to you.

- Preheat the oven to 350°F. Generously brush a 10-inch cast-iron skillet

with butter and place it in the oven while the oven preheats.

- Meanwhile, in a large bowl, whisk together the cornmeal, flour, sesame seeds, sugar, baking powder, baking soda, and salt. In a separate

small bowl or liquid measuring cup, whisk together the milk, Greek yogurt, eggs, melted butter, and 4 tablespoons of the honey. Add the wet ingredients to the dry and mix just until combined. The batter will be lumpy.

- When the oven is hot, remove the skillet and pour in the batter. It should sizzle. Bake for 25 to 30 minutes, or until the edges just begin to pull away from the sides of the skillet, the center of the

cornbread bounces back when touched, and a cake tester or toothpick inserted in the center of the cornbread comes out clean.

- While the cornbread is baking, whisk together the remaining tablespoon honey and the sesame oil. When the cornbread is done, remove

from oven and brush the honey-sesame oil mixture evenly over the top. Sprinkle with additional sesame seeds and serve warm, with more butter or sesame oil, if desired.

Ingredients

- 6 eggs

- ¼ cups soy sauce

- 1 tablespoon loose-leaf black tea or 1 tea bag

- 2-3 whole star anise

- 1 stick cinnamon or 1/2 teaspoon ground cinnamon

- ½ teaspoons salt

- ½ teaspoons orange zest (optional)

- 1 teaspoon Sichuan or regular peppercorns (optional)

When I began to cook for myself in law school, I discovered how very easy these savory, lip-smacking Chinese street snacks were to make at home, and I went through a brief stint where I made them every week in droves. I shared them with hallmates; I peeled them at my desk while studying and tucked them into the fridge to snack on all week. The only problem was that our communal kitchen was through two sets of locked double doors from my dorm room, too far to hear much of anything that happens there, and as it turns out, fatigue from late-night studying and absentminded cooking do not always mix. My tea egg obsession came to an explosive halt one night when I left the pot on to boil, went back to my room, and—yes—fell asleep until the next morning.

So please, don’t do that. And if you do, pray that, as in my case, the student who lives across the hall from the kitchen will hear your eggs exploding in the pot and remove them from the stove before any real damage is done.

- Place the eggs in small pot filled with enough cold water that the eggs

are covered by about 1 inch. Bring the water to a boil, then remove from

the heat and cover. Let sit for 8 to 10 minutes to cook the eggs, then

drain and rinse the eggs with cold water until cool enough to handle.

Take each egg and tap it gently with the blunt end of a knife or the back

of a spoon until the entire surface is lightly cracked. If small pieces flake

off, don’t worry, but do try to keep the shell intact over the egg.

- Return the eggs to the pot. Add the soy sauce, tea, star anise, cinnamon,

salt, and orange zest and peppercorns (if using), then add

enough water to cover the eggs—usually about 4 cups or so—and give

it a good stir.

- Bring the mixture to a boil, then reduce the heat to medium-low and

simmer for about 1 hour. For saltier, firmer eggs, continue to simmer

for 2 or even 3 hours. (See Notes if you prefer eggs that are less well

cooked.) Keep an eye on the liquid as it simmers; you may need to add

water as the mixture boils down, aiming to keep the eggs submerged

in broth. Serve warm or cold. The eggs will keep in the refrigerator for

up to 1 week.

Ingredients

- 1 pound boneless rib eye, New York strip, or top sirloin steak, about 1-inch thick

- ¼ teaspoons salt, or to taste

- ¼ teaspoons black pepper, or to taste

- 1 tablespoon vegetable oil or other neutral oil

- 1 batch Gireumjang

- Korean salt & pepper sesame sauce (gireumjang)

- 1 tablespoon salt

- 1 ½ teaspoons black pepper

- 3 tablespoons sesame oil

All it takes is the smell of sesame oil for my husband to come wandering into the kitchen. Even a small amount can fill up the whole room, piercing and immediately recognizable, yet the smell is a round, mellow one, like a warm, booming laugh. “Something smells good,” Andrew will inevitably say, perking up with Pavlovian interest. “When do we eat?”

When something can rouse an appetite so powerfully all on its own, it needs very little else to become a good meal, and gireumjang, a sandy textured dipping sauce made from nothing more than sesame oil, salt, and black pepper, is proof positive of this. Nutty and toasty, punched up from the salt and warm from the black pepper, gireumjang is typically served with thin slices of barbecued pork belly, or samgyeopsal, but my mother-in-law also favors serving it with strips of sirloin steak. The latter, smoky from a quick sear in a good cast-iron pan, is my favorite.

- Season the steak generously with salt and pepper on both sides. If the steak is cold, let it rest until it comes close to room temperature, 30 minutes to 1 hour.

- In a 10- or 12-inch cast-iron pan or other thick-bottomed skillet, heat a slick of vegetable oil over high until shimmering and very hot. Add the steak and let sizzle energetically for 2 to 3 minutes, until a nice brown crust forms on the bottom side. Flip and cook for an additional 1 to 3 minutes, until the steak reaches your desired doneness. An instant-read thermometer is tremendously useful for checking doneness—medium-rare will read between 130°F and 140°F, medium will read

140°F to 150°F, and medium-well 150°F to 155°F. If you don’t have a thermometer, just use a spatula to press lightly on the center of the steak. At medium-rare, the steak will feel like your cheek, mostly soft but with some structure; at medium, the steak will feel like the fleshy part of your chin, still soft but with more resistance; at medium-well, it

will feel like your forehead between your brows, fairly firm.

- Remove the steak from the heat and let rest for 5 to 10 minutes to let the juices distribute. Meanwhile, make the gireumjang if you haven’t

already. Slice the steak and serve with gireumjang drizzled over top or on the side as a dipping sauce.

Korean salt & pepper sesame sauce (gireumjang)

- Mix together the salt and pepper in a small bowl. Stir in the sesame oil until incorporated. Enjoy, or refrigerate until needed. The sauce will keep for several weeks.