The traditional small plates that kickoff a Korean meal are as varied, and exciting, as ever in the tune of fermented tomatillos and pineapple kimchi.

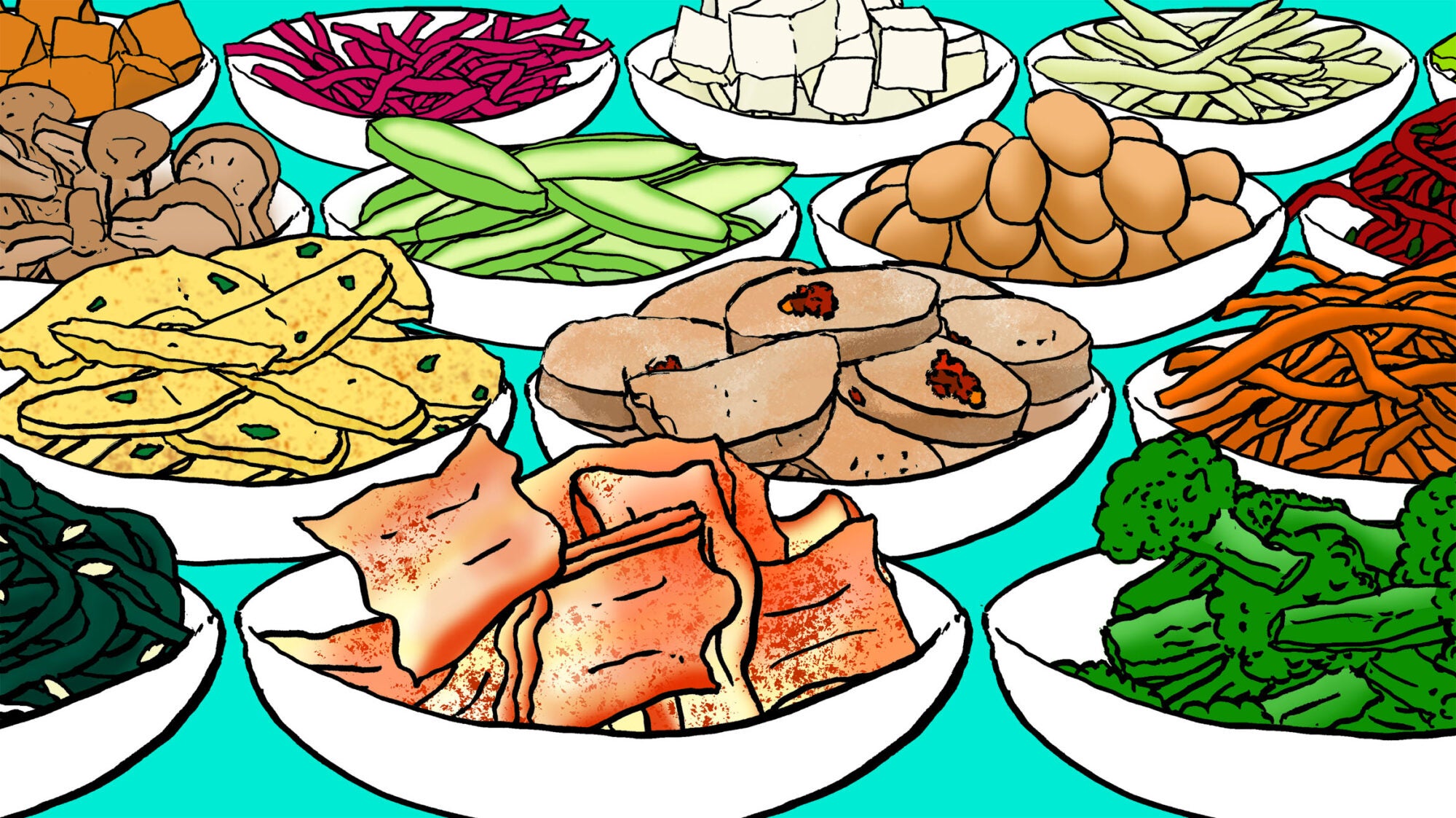

“The thing about banchan is, if you put anything in a small bowl, it can be banchan,” chef Ji Hye Kim says and laughs. She’s joking but also not. Banchan, in Korean cuisine, is a broad category of traditional dishes that are served to accompany a meal. These dishes tend to be vegetable-heavy and cover a variety of techniques, from fermenting (kimchi) and lightly cooking and seasoning (namul) to stir-frying (bokkeum) and pan-frying (jeon), all served in small plates alongside the main dishes.

Colloquially, banchan is often called a side dish, but I find that to be a bit misleading. The hanja for banchan—飯饌—literally means “rice food,” or food to be eaten with rice, which tracks historically. In the 1500s, foreign visitors were shocked by the sheer volume of rice Koreans consumed at each meal. But in the 20th century, as rice became scarcer during the Japanese occupation from 1910 to 1945 and into the postwar era, rice bowls shrank, and banchan spreads became bigger and more varied.

Traditionally made by hand at home in large batches, banchan has lately been modernized. Premade, store-bought banchan has risen in popularity in Korea over the last five years as a practical solution to busy schedules and the growing number of single-person households who don’t need five pounds of kimchi in the fridge. As interest in Korean food beyond barbecue has grown in the United States, pop-ups dedicated solely to banchan have sprung up over the last two years as well.

In Los Angeles, Jihee Kim’s pandemic-era pop-up Perilla, which offers a variety of playful, creative banchan like fermented tomatillo and charred okra in soy marinade, is expected to open a storefront this year. In Oakland, at Joo Doo Boo, Steve Joo makes his tofu (called dubu in Korean) in-house, alongside a rotating array of six banchan centering California produce. In Seattle, Sara Upshaw pops up at farmers’ markets and stores with gluten-free banchan that preserves traditional Korean flavors as Ohsun Banchan, named for her grandmother.

Even as banchan is becoming more known, it may still be largely unfamiliar to non-Korean diners who aren’t sure how to incorporate it into a meal. Banchan is typically served first, before the main dishes arrive, so they’re often mistaken for appetizers. Small and light, they’re also unlike the heavy sides served alongside a steak dinner or Southern barbecue.

“Banchan isn’t a separate course that you’re eating with your main,” says Danny Lee, co-owner/chef of Anju, a modern Korean restaurant in Washington, DC. “It’s actually meant to accentuate and enhance your meal from start to finish.”

For example, take seolleongtang, a thick, beefy soup made by simmering ox bones for hours until the broth becomes milky white. It’s delicious on its own, heavy and rich, but take a mouthful of seolleongtang with rice, then take a bite of crunchy, acidic kkakdugi, and the whole meal comes together.

“What I like about banchan is that I think Korean food has a lot of faith in the diner,” says Ji Hye Kim, chef-owner of Miss Kim in Ann Arbor. “It’s almost like a deconstructed eating experience, because everything comes spread out, and you, as a diner, decide what flavor and texture combinations you want to have in your mouth at any given moment.” It might not feel like the most intuitive way of eating, she concedes, unless you have practice with it.

Typically, banchan is offered both free of charge and with unlimited refills as part of Korean hospitality. The price is expected to be built into the menu, an idea that doesn’t really work in reality, given the fact that many diners expect Korean food to be cheap. As a way to counter the rising cost of labor and ingredients while mitigating food waste, some restaurants, including Anju, have started charging for banchan. Lee says he’d like to see more people recognize the amount of effort and time that go into banchan, which Angel Barreto, executive chef at Anju, echoes. “I think ‘respect’ is a big word,” he says. “It’s a mindset we have to change in people because, often, people think pan-Asian cuisine should be cheap. It takes a lot of care and dedication to get to this point.”

As I started to eat banchan more thoughtfully, I found myself thinking a lot about sohn-maht, which literally translates as “hand taste.” It is that subtle thing that makes each person’s banchan different, an individual taste that comes from years of experience cooking. When speaking of the challenges of making banchan in a restaurant, Ji Hye Kim admits that this is the hardest part. She can write down an exact recipe, weigh everything out, and make the sauces herself, but there’s an instinct that’s difficult to teach. “I think that’s what mothers and grandmothers have from all their experience making banchan,” she says. “Just the right amount of touch.”

That doesn’t mean knowledge can’t get passed down. Sunny Lee, a chef based in New York who recently completed a residency of her pop-up Banchan by Sunny at Peoples Wine, grew up in Andover, Massachusetts, in a predominantly white community. She occasionally cooked Korean food with her dad but went to culinary school where she trained in French-style cooking. Lee worked at Blue Hill, Eleven Madison Park, and Estela before finally admitting that all she wanted to do was make kimchi. She started learning to make Korean food on her own, until she found herself at Brooklyn’s Insa, under the tutelage of chefs Sohui Kim and Yong Shin, and took on their banchan program. Kim became a mentor to her, introducing her to the concept of the ajumma and passing on advice, including a rule about banchan she still applies today.

“I definitely feel like a banchan table needs to be balanced,” Lee says. When she first started at Insa, Lee was fully seasoning each dish, thinking of every banchan as its own plate. Kim advised against that. As Lee says, “She was saying to me, instead of looking at banchan like a dish, zoom out, and look at the table like a dish. I thought that was an amazing piece of advice that I think about every time I make a banchan selection for anybody.”

This generational influence is also evident at Anju, where Lee’s mother, Yesoon Lee, guides the process. When opening Anju in 2019, Barreto says they made an intentional decision to prepare banchan in the traditional way, taking no shortcuts and, as Danny Lee says, “showcasing Korean techniques” like fermenting, blanching and seasoning, and lightly pickling. Anju’s banchan offerings, which include pickled mu, oi-muchim, and chayote-jjangachi, work as a foundation of Korean cuisine that creates familiarity for the diner, allowing the chefs to be more creative with their main dishes. For example, Barreto makes his jajangmyeon with lamb and palm sugar instead of the traditional pork, bringing a warmer, earthier flavor to the popular Korean-Chinese noodle dish. It’s just different enough to feel unfamiliar—but then eat a bite of traditionally made kimchi, and the whole meal makes sense.

“It’s a mindset we have to change in people because, often, people think pan-Asian cuisine should be cheap. It takes a lot of care and dedication to get to this point.”

Down in Miami, sisters Michele and Jennifer Kaminski use their mother’s banchan recipes as the backbone of their bibimbap delivery and takeout business, 2 Korean Girls. Operating out of a ghost kitchen since 2020, they make bibimbap using the very Korean eating method of mixing whatever banchan is in the fridge with rice, gochujang, and sesame oil. Michele Kaminski says they chose four to five banchans (including pickled radish, braised potatoes, and sauteed spinach) from the repertoire they grew up eating in their mother’s restaurant in Indiana, using her exact recipes as she advises.

This passing down emphasizes how banchan is an anchor to the Korean bapsang, or dinner table. While many Korean American chefs play with quintessential Korean dishes, from using foie gras in kimbap to combining chopped cheese with ddeok, I was surprised to see how much of the Korean American approach to banchan still skews traditional.

This makes sense, though. Banchan, as a dining concept, is still relatively new to American dining, and it can also be a point of entry for diasporic Koreans to connect with their Korean heritage. On TikTok, Korean American creators like TeakEatz, EunaeEmily, and ChefChrisCho have built audiences with videos showing how to make traditional banchan like gamja-jorim, oi-muchim, and eomook-bokkeum.

“It’s how Korean food is meant to be eaten,” Danny Lee says. A bowl of rice, a rich main dish, and, in between bites of that savory main, a bite of kimchi, kongnamul-muchim, or doraji-namul. A full, balanced meal, all on one table.

Anju photo by Alex Lau.