Coating a pizza with bulgogi or boba isn’t about going viral—it’s about reinventing the tomato-cheese formula entirely.

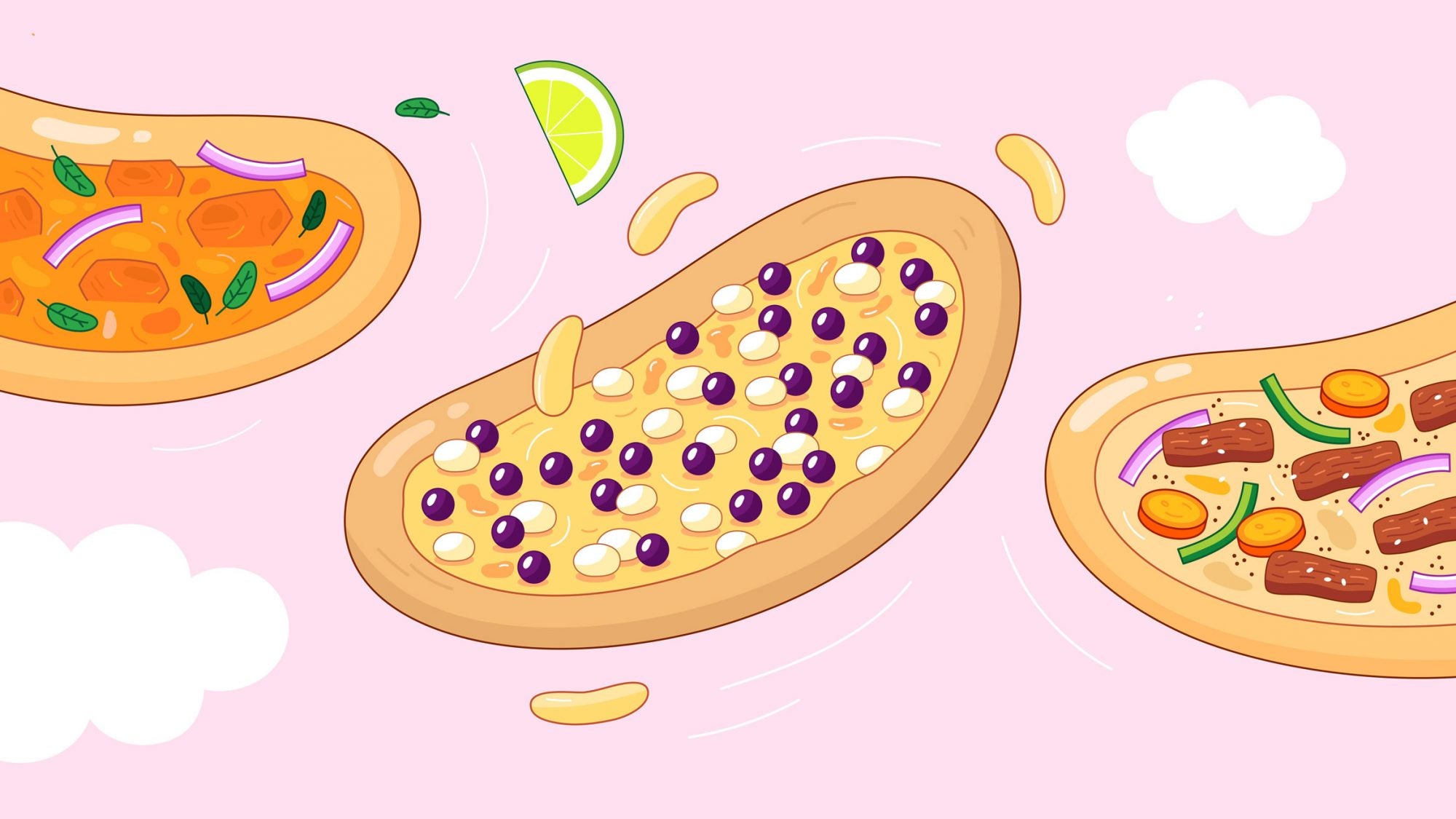

Boba pizza isn’t as atrocious as it might sound. They sell it at Domino’s Pizza in Taiwan, where plump tapioca pearls, previously soaked in sugar, are spread out evenly across a thin pie, sprinkled with miniature white mochi balls and topped off with a diluted honey drizzle. A layer of mild industrial mozzarella cheese in the middle holds everything together. It’s a well-executed contrast of sweet and savory, further brought to life by the squeaky textures from the boba, mochi, and cheese. And if it’s not enough boba for you, you can order it stuffed inside the crust as well. Flavor-wise, the whole thing goes down like a cross between a honey cake and a soothing, warm flan.

This may all seem like a publicity stunt, but boba isn’t that much of an outlier when it comes to pizza toppings in Asia. It exists comfortably in a part of the world where unconventional toppings—at least for the Western gaze—are the norm, like bulgogi on pizza in Korea, butter chicken in India, and natto in Japan. While all these pies may seem like they exist for shock value—occasionally deemed “utterly revolting”—they were actually invented to cater to local tastes. The virality is just a positive by-product—a factor that offends mostly outsiders.

I was first introduced to boba pizza by my friend Lev Nachman, a visiting scholar at National Taiwan University whose Twitter thread about eating a boba pizza went viral in 2019. “What I really loved about my boba pizza tweet going viral is that it managed to offend people in pretty much every country,” he says. “I had tweets responding to me in every language possible, from Arabic to Thai to Russian, and people yelling at me about what a disaster and what a monstrosity this thing was.”

“Texturally, the squeaky cheese goes along with boba. It’s not so distant that it feels out of place. Adding mochi gives it another kind of chewiness—so you have to like chewy things,” he says.

The inventor of boba pizza was not some marketing executive at Domino’s with a desire to go viral at any cost. It was Chen Yun Yu, who owns Foodie Star—a Taiwanese eatery in the southwestern Taiwanese city of Chiayi. She tells me that she’s never been a fan of traditional Italian-style pizza with tomato sauce and melted mozzarella, and she prefers her pies dressed with flavors that she’s used to, like sweet adzuki bean, fruit with condensed milk, curried pork, and boba.

“What I really loved about my boba pizza tweet going viral is that it managed to offend people in pretty much every country.”

“The boba is really just for the texture,” she says of her signature pizza. In Taiwanese cuisine, texture is a cornerstone, and one of the most classic textures is described as “Q” (pronounced the same in English as it is in Mandarin). Taiwanese people use the word “Q” or “QQ” as an approximation of the concept of al dente, except that something that is Q has a bit more of a spring to it—more gummy bear than well-cooked pasta. “I take into account local tastes. We don’t cater to foreigners. We cater to locals,” says Chen, defending herself.

Much in the same way that American Chinese food is completely different from the food actually served in China, pizza in Asia is oftentimes unrecognizable from the margheritas, Sicilians, and dollar slices of the world. The typical rules that govern pizza in the West don’t apply at all in the East, because the culture of pizza is relatively new, meaning people don’t have a preconceived notion of what pizza should taste like, and because classic ingredients like sweet basil, prosciutto, and mozzarella are extremely difficult to find. “My mother often recalls how domestic ovens started becoming available in India in the 1970s, and the first thing everyone wanted to make was pizza,” says food writer Sejal Sukhadwala. “People were fascinated by it. The pizzas at the time were like traybakes, cut into squares or rectangles, and the toppings were an imitation of pizza margherita, except that local processed cheeses were substituted for mozzarella, and green chiles were sprinkled liberally.”

Chain pizzerias like Pizza Hut and Domino’s began opening up throughout Asia in the ’80s and ’90s, introducing the dish to the masses. But instead of serving the same pizza they make in the United States, they found that business was much better when they adapted to local tastes. In India today, pizzerias can be found in every major city, but they serve pies layered with bright orange tandoori chicken, spiced butter chicken, and soft cubes of paneer for the vegetarians. “I wouldn’t call them Indian pizza places. They’re just pizza places,” explains Amrita Amesur, an Indian food writer based in Mumbai. “I grew up Hindu, so we don’t eat pork or beef at home. Pepperoni is still a little bit foreign, and it’s still quite rare. It’s only for people who are familiar with Western flavors.”

“Boba pizza is not bad. It’s really good!” she says. “It’s actually quite difficult to make it taste bad.”

By now, many of these quirky flavor combinations have become so iconic that they’ve actually been imported back to the West. When pizza chains first started debuting in Korea in the ’90s, for example, bulgogi pizza was the standard. So, at Koreatown Pizza Company, a Korean-style pizzeria in Los Angeles, their specialty is a massive pie they call the Kingsley, which is basically Korean barbecue reincarnated on a pizza. Marinated bulgogi and corn cheese make up the bulk of the dish, anchored by a massive fried onion flower in the middle. The crust is stuffed with sweet potato mousse, and that whole thing is topped with a sprinkling of cheddar. “People can get pizza anywhere. So we might as well have pizza that everyone likes, but also do things that most people can’t get,” says co-owner Johnny Lee.

There’s a freedom to suspending the usual formula of tomato sauce and cheese in a greasy cardboard box, and allowing pizza to be a blank slate—both as a dish and as a concept. In China, Pizza Hut has rebranded itself as a fine dining destination, with an extensive menu that includes steak, noodles, salad, and cake. Some locations even have a full wine list. I still vividly recall going on a date at a Pizza Hut in 2012 in the eastern Chinese city of Xiamen with my boyfriend at the time. Located on the very top floor of one of the tallest skyscrapers in town, it was graced with a full panoramic view of the city. We ordered a glass of red wine; our pizza was served on a plate with a knife and fork. It wasn’t a particularly great meal, but the atmosphere was divine. It was the first and only romantic meal I’ve ever had at a Pizza Hut.

While there does exist a niche subset of Italian, Chicago, and New York–style pizzerias in Asia that strive to mimic their original regional variant as much as possible, these establishments tend to be confined to top-tier cities and are catered toward a well-traveled and wealthier client base. The average person in Asia has never had a proper Neapolitan pizza, or even pure mozzarella cheese, and instead sees pizza as a blank vessel for their favorite flavors.

Chen laughs when I tell her what the international response to boba pizza has been like. “Boba pizza is not bad. It’s really good!” she says. “It’s actually quite difficult to make it taste bad. It’s only bad when the texture is not QQ enough, but it’ll never be disgusting to the point that it’s inedible.”