A new generation of chefs and activists are using dinner parties to help refugees and immigrants affected by the election.

It’s dark when we arrive outside the Hopewell Presbyterian Church in Hopewell, New Jersey, so I follow the burly guy carrying a foil pan of fried turkey. In front of us is a parade of other guests—each carting a covered platter, a vintage Pyrex casserole dish, a slow cooker, or more foil trays. As I enter, the unmistakable odor of church basement hits me along with the Thanksgiving-like smell of the crisped turkey skin.

My husband and I know none of the people around us, but we are here to support Interfaith-RISE, a one-year-old New Jersey–based organization devoted to helping settle newly arrived refugees. Like many businesses and organizations operating in the aftermath of the election, this one had decided to use communal dining to support the people most affected by tenuous immigration policies.

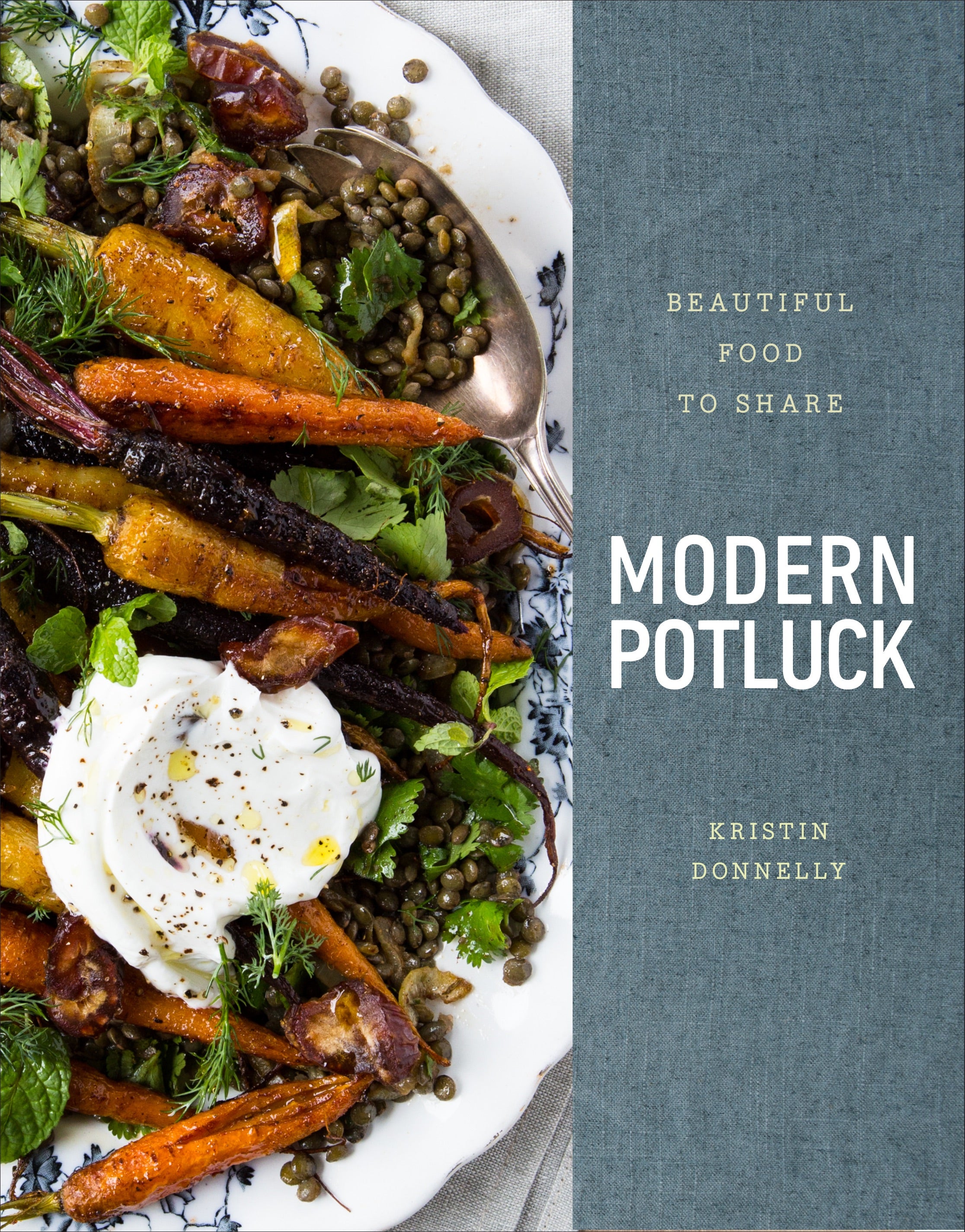

We all head to the industrially lit commercial kitchen, where people vie for counter space to put the finishing touches on dishes (and to carve the turkey). My contribution—spiced carrots with lentils—is ready to serve, so the bubbly event organizer, Maricel Hermann, leads me to a more warmly lit room where folding tables covered in vinyl floral tablecloths are arranged in a long rectangle. I spy a sweet-potato salad with scallions and a Moroccan-style carrot salad and set my dish next to them, in what is now the unofficial orange vegetable section.

I love potlucks. After all, I wrote a book about them. But this one, in March—drawing 133 people and 68 dishes—is the largest one I’ve been to in over a decade. Or maybe even ever. I end up with the most international sampler platter I have ever encountered: Persian jeweled rice, chicken biryani, masoor dal, and a square each of kale frittata, corn-and-greens enchilada, and eggplant tart.

The event’s focus is more humanitarian than political, but of course my tablemates and I can’t avoid discussing the election that rocked all of our world views. The conversations are similar to those I have with friends daily: We discuss the fears we have and what new policies might mean for immigrants, the environment, racial justice, public education, and the growing wealth gap.

Like many organizers of these benefit dinners, after the election, I felt the almost desperate need to do something. I back-burnered a book proposal to instead launch Potluck Nation, a twofold project that both explores the power of the potluck and encourages people to use potlucks as forces for good. To help people plan larger events, like the one in Hopewell, I created a downloadable checklist of logistical information to consider, including must-ask questions when considering a space for a potluck and tips for items to bring on the day of the event.

Photo by Nik Sharma

Since the election, the food industry has banded together in incredible ways to raise money for organizations that will likely need the funds over the next few years. Late last year, Bon Appétit started a series of dinners called Family Meal, to benefit organizations that champion immigrants’ rights. Restaurants in Chicago held bake sales to donate money to Planned Parenthood, and coffee shops across the country coordinated fundraisers for the American Civil Liberties Union.

But this sentiment has spread far beyond businesses and commercial spaces and into people’s homes. Syria Supper Club, based in Maplewood, New Jersey, pays refugees to cook food from their country, after which they share the meal with new American neighbors. The organizers are currently raising money to expand the supper club into a larger and more evolving organization called the United Tastes of America, which they hope will provide catering services, cooking lessons, and even a summer camp for the children of refugee families. The similarly-named Syrian Supper Club, based in the UK, raises money for humanitarian aide in Syria by encouraging people to host their own fund-raising dinners.

Nik Sharma, author of the blog and San Francisco Chronicle column A Brown Table, started a monthly supper club at his home in Oakland, California, in which he cooks food inspired by his roots as an immigrant from India and raises money for different organizations. (His first, in March, was sponsored by West Elm and benefitted the ACLU.) In his words, “My goal is to use my food and cooking as a tool to not only introduce people to traditional Indian food but also show how I adapt flavors and techniques as an immigrant.”

For people looking for easy ways to host their own dinners, there’s Dine 4 Democracy, an initiative that is truly democratic in spirit. Created by three twenty-something friends who work to promote democracy and press freedom internationally, the organization provides people with simple ways to learn about the issues affecting the U.S. and take action.

Each month, they suggest a topic people can discuss at dinners held in homes with friends, almost like a book club. They provide mailing list subscribers and Facebook followers with a PDF list of talking points, action steps, and an organization or two for donations. After launching in February with the topic of health care, 80 people attended 11 dinners and raised over $1,000 for Families USA. In March, the group’s focus was immigration.

“We want to help people sift through the noise and take the time each month to focus on one issue in a way that’s not overwhelming or a burden,” says Paul Rothman, one of the Dine 4 Democracy founders. Even better if they can do it over a good meal.

It’s this sentiment that led all of us to a church basement in New Jersey to dine with strangers on Chinet plates, hoping to help people more vulnerable than ourselves and to connect with others who wanted to help as well. These feelings are what led organizer Maricel Hermann, an admittedly type A financial-industry project manager with almost no event-planning experience, to launch Foodies for Refugees and organize a potluck like this one for the first time.

“I’ve been craving community, and I know others are as well,” she tells me after the event. “People have been feeling like they need to be together doing something for a good cause. A high-dollar fund-raiser might have been a more efficient way to raise money, but I wanted to create something accessible for everyone.”

Top photo: Syrian Supper Club