As a Christian who grew up in Beirut, Anissa Helou may be an unlikely expert on the expansive foods of the Islamic world. She’s done her homework.

Anissa Helou recalls standing at a slaughterhouse behind a live animal market in Sharjah, an emirate 30 minutes outside of Dubai. As she writes in her ninth and most recent cookbook, Feast: Food of the Islamic World, she was there for camel hump, a prized cut of meat in the United Arab Emirates that she’d been seeking out for years—ever since she was denied a taste at a dinner where the women and men were separated and the women served lesser cuts of the animal. The camel arrived in the back of a van, sitting quietly, legs folded. When it realized its fate, it started to bray, but when the moment of slaughter arrived, it didn’t fight “when one of the butchers said ‘Allah Akbar’ and slit its throat,” she writes.

Helou carried her prize to her brother’s house, where she massaged it with saffron, rosewater, and b’zar, an Arabian spice mix of black peppercorns, cumin, coriander, cloves, cinnamon, cardamom, and chiles, and roasted it. “The hump looked gorgeous as it came out of the oven, crisp and golden,” she writes.

The moment is one of many in the book that takes readers inside a food culture that is often impenetrable to outsiders unfamiliar with the region’s religious and cultural customs, a culture in which the greatest feasts are had around the family or mosque’s communal table, not in restaurants. The book documents 300 recipes originating in Muslim lands that stretch along a nearly 8,000-mile arch from Morocco to Indonesia. It also serves as a traveler’s log, documenting how Helou, who was born into a Christian family in Beirut and left for Europe when she was 21, became a foremost expert on the foods of the Islamic world.

Some of the most meaningful travel for the book was done during Ramadan or Ashura, a solemn day for Shiite Muslims. For most travelers, she says, “it’s a very closed time of the year because everyone’s with family and friends.” But with her connections, fluency in Arabic, and knowledge of the region and its customs, she is able to pierce that veil.

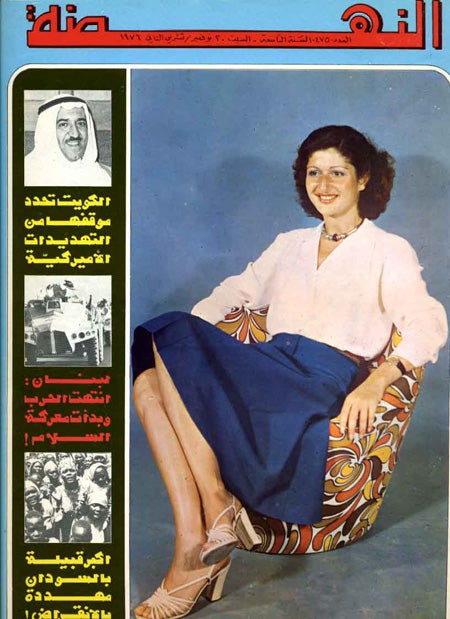

In Stone Town, Zanzibar, Helou ignored a suggestion to stay inside as locals broke the Ramadan fast, warned that the only people wandering the streets would be “villains,” she tells me over a dry cappuccino at Mah-Ze-Dahr bakery in the West Village on a visit in May, her architectural gray and white hair making her unmistakable. “They wait for the food in a Zen way…. The night is given over to feasting—that for me is a very meaningful time,” she adds as she describes the state of mind she witnessed on that trip and many others.

She came across a mother and daughter cooking on their doorstep, preparing mkate wa ufuta, a sesame bread cooked over embers and served at futari or iftar, the meal that ends the Ramadan fast. With the help of a local guide, she captured their recipe.

Unlike many other English-cookbook writers with a focus on the Middle East, Helou says, “I’m a native as it were…. That life is still a part of my life, even though I live abroad.” She grew up in the 1950s and ’60s in Beirut, in an affluent home in the Muslim part of town with one Lebanese and one Syrian parent; since leaving, she has shuffled back and forth. In the late 1970s and early ’80s, it was for work in the art world, helping the daughters of the Kuwaiti royal family purchase Islamic art. “It was great because they had three cooks,” she says. “Every day I would say, ‘Today we should have this or that,’ and we’d have these amazing [meals].”

She learned to cook first through osmosis, from those three cooks, and before that from her mother. She was a kitchen pest, always watching what was being cooked but refusing to join in as a feminist statement. “I didn’t want to be domesticated,” she explains.

Politics, albeit of another ilk, brought her back to the kitchen and helped spur her first cookbook project, Lebanese Cuisine, a collection of recipes from her home country. The Lebanese Civil War brought upheaval, and Helou “wanted to produce this book for all these kids who had been displaced,” she explains. For Sami Tamimi, the coauthor of Jerusalem and a partner of Yotam Ottolenghi, the book was “like my bible,” he says. He would turn to it for information and ideas, as Lebanese food is similar to the Palestinian food Tamimi was raised on.

Tharid, a meat-and-vegetable stew rumored to have been a favorite dish of the Prophet Muhammad

“She’s, I think, the only real Arab food critic,” he adds. “If I’m not sure about something to do with Middle Eastern food,” he says, he turns to her books. Since Helou’s first book came out in the late 1990s, she’s gone on to author books that explore Mediterranean street food, Moroccan cooking, the sweets of the Middle East, and more. Each time, she collects more information and recipes, much of which inform entries in Feast.

Still, when she was asked by a former agent to write a Middle Eastern compendium, she declined, citing the works of Claudia Roden and Paula Wolfert. But the Arab Spring altered her thinking. She saw a religion and culture she feels a kinship with vilified, and a cookbook was an opportunity to celebrate it.

The predominance of Islam is how Helou joins together the countries in Feast. While these are the foods of the Islamic world, some will find it hard to define them as Islamic foods. Sami Zubaida, a scholar of Middle Eastern politics and food, explains: “The only factors common to the food of Muslims are ritual, not gastronomic: Halal slaughter and avoidance of pork…. Foods of different Muslim regions are as diverse as the regions,” he says.

Helou, however, unites the region culinarily through common ingredients like bread, rice, whole animals, dates, and cooking practices tied to Ramadan and other holy days. She shares a recipe for tharid, a meat-and-vegetable stew served atop thin flat bread, which she writes “is said to have been the Prophet Muhammad’s favorite dish.”

Through the book, she takes us out on the patio of her grandmother’s home in Beirut for Sunday grilling, to eat stuffed mussels on the streets of Istanbul, to India, where she traces the origins of Scotch eggs to nargisi kebab, a dish from the Mughals, a Muslim dynasty that stretched across Afghanistan and much of India. And along the way, she connects essential dishes in the Muslim world, like kebabs, which vary in preparation but are available throughout that 8,000-mile stretch. She also explains the religious and cultural significance of bread, from Egyptian pita called aysh (meaning life) to a custom in Morocco of carrying raw dough to local bakeries to be cooked in communal ovens just before iftar.

As a Christian, Helou is an unlikely author for such a book. But Yvonne Maffei, of MyHalalKitchen.com, who converted to Islam, says Helou’s Christian upbringing may strengthen the book. “She’s on the outside in a sense,” says Maffei. “The fact that she’s not exactly celebrating the holidays — she’ll probably pick up a lot of nuances that someone who is in it probably won’t observe.”

What she observes is captured without compromise. Many of the recipes are challenging, coming from a section of the world where cooking is often a communal or familial act, at times occupying days leading up to a feast. Helou’s recipes gracefully capture this world where food, religion, and culture are deeply intertwined, opening it to a broader audience and presenting it unfiltered.

She explains: “A recipe that’s given to me, that’s passed on from generation to generation, needs to stay [as is]. I’m recording history.”