Montagne and a young generation of foreign-born chefs are changing the way Paris thinks about dining out.

Alessandra Montagne fondly remembers the time she first came to Paris, from Brazil, 18 years ago. “As soon as I arrived, all of the smells, the diversity, the terroir that we don’t have in Brazil,” she says, breathing in quickly. “I discovered a visceral passion for cooking in France.”

Montagne, the proprietor and chef of the unpretentious, 28-seat Tempero (“spice” in Portuguese) in Paris’s 13th arrondissement, grew up in the tiny rural village of Poté in Brazil’s Minas Gerais region, where there was no electricity when she was a child. Raised by her grandparents—her grandmother was a seamstress and her grandfather a civil servant—she lived on a farm that allowed the family to be self-sufficient, raising chickens, pigs, cows, and Brazilian produce: mangos, pineapples, guavas, acai berries, and the grapelike jabuticaba.

Though Montagne had no formal culinary training before coming to Paris, her roots are serving her well now as she and other chefs like her are reshaping the city’s cuisine with their globe-spinning outlook. It was not long ago that food writer Michael Steinberger was declaring in his 2009 book, Au Revoir to All That: Food, Wine and the End of France, that the Golden Age of French cuisine was over. Spain and Nordic countries were on top, claiming prestigious culinary awards, while France was mired in the past. But that’s evolving. Today, a classic French restaurant serving sole Véronique and quenelles de brochet (helmed by American chef Daniel Rose), Le Coucou, is setting the culinary agenda in New York, while foreigners—and French chefs using foreign ingredients and classic technique—are reinvigorating French food in Paris.

From the casual Israeli grill Miznon, offering boeuf bourguignon in a pita, to Atelier Rodier’s modern French menu enlivened by the flavors of chef Santiago Torrijos’s native Colombia, to French chef Adeline Grattard’s deep dive into Chinese cuisine, Paris has been lifting its head and seeing there’s a big, wide world out there.

Montagne’s unlikely combination of French, Brazilian, and Asian cuisines is part of the city’s multilingual conversation. Tempero has the added advantage of offering a three-course meal for a very reasonable price, 21 euros, showing the influence of a chef who grew up believing economy was a virtue and saw poverty all around her. “I wanted to offer an inexpensive menu so everyone could come to eat here,” Montagne explains.

She uses her childhood memories of smells and tastes to inform her cooking in France: ginger, lemon, passion fruit, sweet potato, banana leaves, green bananas. Then she adds in a dash of Asian inspiration, and French technique, to foment her unique style. “The more time passes, the more memory I have of smells and tastes,” Montagne says. “I know that this texture, taste, or smell goes with this or that ingredient, without needing to test or taste anything. Experience and work help you develop this ability.”

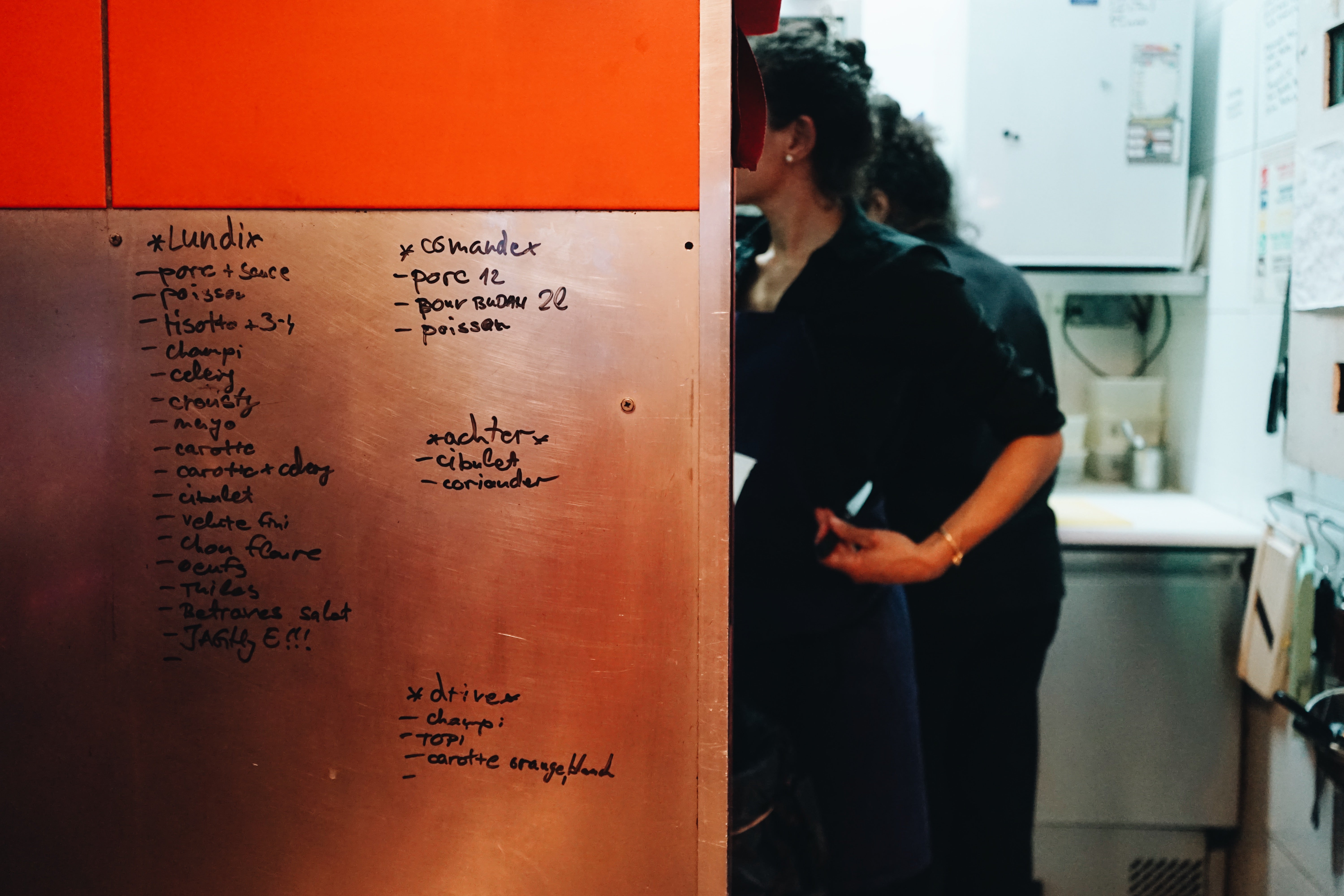

Employing her finely honed sense memory spanning multiple cultures and a thrifty ethic—she picks her own produce on local farms, scours the Marché Président Wilson (across from the Palais du Tokyo), and uses all parts of meat and produce to eliminate food waste—she and her multicultural kitchen brigade (featuring staff from Serbia, Costa Rica, and Lebanon) are able to offer their version of what she calls “cosmopolitan cuisine.”

When pressed, she explains the term. “Right now on my menu I have black beans, but not as they’re served in Brazil,” the curly-haired chef says in her lilting French. “I cook them with a lot of herbs, leeks, and bulgur, then I shape them in the form of a sausage. I let them rest, and once they take shape, I put them in the oven. Voilà, my version of a boudin noir.”

On her daily blackboard menu—which proposes three starters, three main courses, and three desserts for weekday lunches, and Thursday and Friday dinners—you might see a beef foie gras terrine with a Vietnamese pho–inspired broth scented with cilantro and scallions, shiitake risotto, or Hokkaido squash velouté with a touch of vanilla.

“You always start from basic French cooking, which you have to master perfectly,” she says. “Then you add a bit of yourself. French cuisine is welcoming in the sense that you can add ingredients from elsewhere once you understand the basic techniques.”

Montagne did not originally come to Paris to be a chef. She meant to study French at the Sorbonne for one year only, but Paris and its sights, smells, and tastes captivated her. “Everything was new,” she says with animation. “I was euphoric with joy.” (Another attraction of Paris, she admits, was meeting her Vietnamese-French husband, Olivier; they were recently divorced but remain on good terms.)

A primary-school teacher in her native Brazil, and an executive assistant once she came to Paris, Montagne often entertained her new Parisian friends, cooking classic French dishes, such as boeuf bourguignon and chicken Marengo, that she taught herself by reading cookbooks or researching online. “All my friends told me, ‘Alessandra, what you made is delicious. Why don’t you become a chef?’” In 2008, at the age of 30, she decided to enter cooking school.

“I felt happy and afraid at the same time,” Montagne remembers. “But it was wonderful because it was what I wanted to do.”

As part of her training, she had an influential apprenticeship with Michelin-starred chef William Ledeuil at Ze Kitchen Galerie, known for its inventive incorporation of Asian flavors.

Ledeuil remembers Montagne as an enthusiastic, warmhearted young woman “who absolutely wanted to learn something.” Asked whether he has ever been to Tempero, he says with a laugh, “Every time I try to go, it’s booked.”

Montagne continued her training with a short stint at Yam’Tcha, the acclaimed French-Chinese restaurant on the rue Saint-Honoré presided over by Adeline Grattard. She sought out Grattard not only to learn culinary techniques but specifically because she was a woman. Both chefs had young daughters at the time. Grattard’s daughter was two, while Montagne’s was four.

“As a woman, I wanted to know how she managed to have a family life,” Montagne remembers. “And she managed to do everything brilliantly. She went to get her daughter [from school] at 4:30, she gave her a snack.… I said to myself, ‘It’s possible, in fact.’”

With her husband, Olivier, Montagne launched Tempero in 2012, at the site of a former Chinese restaurant, not far from where she lived. The restaurant has since attracted applause from the influential Michelin and Gault & Millau guides. This year, she was filmed for an episode of Planète Chef, a documentary series on foreign chefs in France—inspired by Netflix’s A Chef’s Table—to be broadcast next year in France. Yet perhaps more important to Montagne, Tempero’s combination of fresh ingredients, inventive cooking, and reasonable prices found immediate success with the residents of her quartier—and she has the full reservation book to prove it, as Ledeuil discovered. (She plans to open a second restaurant this year.)

“I love sharing, giving something to other people,” Montagne says of being a restaurateur. “It’s ephemeral because a meal is consumed quickly, but I feel like I’m doing something good for others.”

Adding to the rich culinary conversation in Paris, by showing how French cuisine can be revitalized with new inspirations, is her way of paying it forward. When asked about the future of French cooking, Montagne says, “It’s always changing—and changing in the right direction.”