Opinions are strong, but science (and a few strong-willed home cooks) tackle the matter.

Hi, my name is Yasmin, and I’m a raw-chicken washer. Until fairly recently, I thought this was typical kitchen protocol: A quick rinse of the cavity and appendages and a thorough dry before cooking—at least that’s what we did in my Persian household when I was growing up in Boston. But while working on my upcoming cookbook, Keeping It Simple, a British food stylist told me that recipes published in the U.K. should never have that recommendation. Turns out, the National Health Services warned people to stop washing their chicken some years back, and I’d look like a fool contradicting respected chefs like Jamie Oliver and Nigella Lawson (not to mention the NHS).

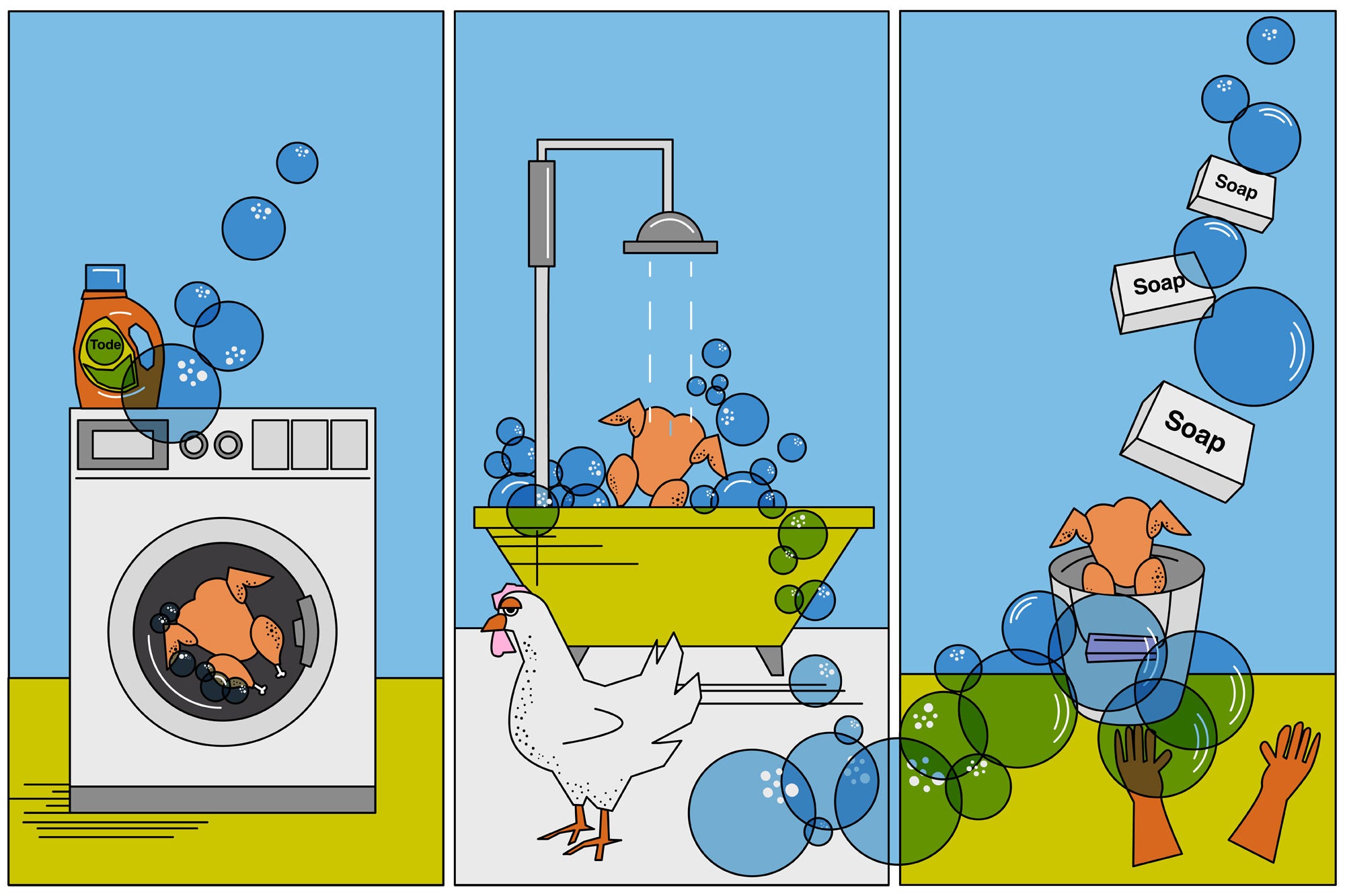

The argument against chicken washing is simple: Bacteria that causes food poisoning (like salmonella or campylobacter) from raw chicken can splatter onto your clothes and around the sink and counter, spraying any place food would come into contact with. The CDC estimates that about 1 million people per year fall sick for this reason. One would think being vigilant about washing anything that raw chicken juice came in contact with would be a solution, but apparently not.

Scientifically speaking, cooking is the most efficient way to get rid of harmful bacteria, and the excess moisture can negatively impact the cooking process. When I ask TV chef and cookbook author Ming Tsai about it, he claims harmful bacteria are killed off when chicken hits 165°F internally. Kenji Lopez-Alt, an expert on the science behind cooking and author of the The Food Lab, explains that adding water to the exterior of a piece of meat won’t help it cook, either: In fact, more energy is needed for the water to evaporate—energy that could have been used for browning or crisping it instead.

Despite warnings from the CDC, NHS, respected chefs, and valid scientific evidence that it’s not a great idea, people, like me, continue to wash. It’s like the foodborne-illness warning on restaurant menus that diners blatantly ignore every time they order oysters or a medium-rare burger. You know you might get sick, but you do it anyway. In that same vein, if washing chicken can make you sick, why do some people ignore the warnings against it and continue to wash? It has to do with the quality of the chicken and household habits.

After growing up in India, chef Romy Gill MBE of Romy’s Kitchen in Bristol recalls, “My parents used to say if there is mud or anything else that is on the food, then you wash it; otherwise you don’t.” This seems fairly intuitive: We wash things that are visibly unclean or smell. Today, Gill no longer washes her chickens, because she purchases organic, plastic-wrapped ones in the U.K.—though that plastic-wrapped chicken gives others a reason to wash.

Scientifically speaking, cooking is the most efficient way to get rid of harmful bacteria, and the excess moisture can negatively impact the cooking process.

It does seem natural to want to get rid of that murky, pinkish liquid that collects inside the plastic, snaking its way around the meat—even if it isn’t technically killing off bacteria. “Chicken in packages sometimes looks icky. The urge is to wash it,” says author Marion Nestle, a nutrition and food studies professor at NYU. After a recent warning from the CDC, pro-washers defended their practice on Twitter. One skeptical user, @MissAuty_baby, voiced, “So we’re supposed to just ‘cook off’ all that gunk from it sitting in a maxi pad for god knows how long?” And though he acknowledges that this is not acceptable to health officials, chef Jonathan Waxman believes in a hot-water rinse. To him, removing all the plasticized liquid helps to make for a pure chicken flavor, since he grew up raising chickens.

Chef Virgilio Martinez of the restaurant Central in Lima echoes a similar sentiment regarding where the chicken is sourced from. He usually knows who is growing the animals, so he feels that “there is a taste, soul, and texture” and avoids washing them. But if the chicken has been stored somewhere and absorbed a nonchicken taste, he rinses it to lose that. How the chicken was raised in terms of feed and living space can make a difference in how it tastes, especially when you’re talking about factory chickens living in tight quarters that are often plied with hormones to speed their growth and antibiotics to limit the spread of disease.

Martinez grew up watching his mother rinse chicken in cold water, but he attributes the practice to an old-fashioned mindset of needing to wash everything. Similarly, chef George Mendes of Aldea in New York says his mother did the same, and now he does it “simply out of habit,” but he always blots it dry before searing or roasting.

Whether washing chicken stems from a strong conviction from old habits or an urge to clean up any packaging-related issues, there isn’t a right or wrong answer—as long as you clean up after yourself. Lopez-Alt says he remembered thinking it was strange the first time he saw someone washing chicken in college, but “the same the person who washed the chicken thought it was strange that I didn’t. I remember her walking into the kitchen and asking me, ‘Aren’t you going to wash that?’”