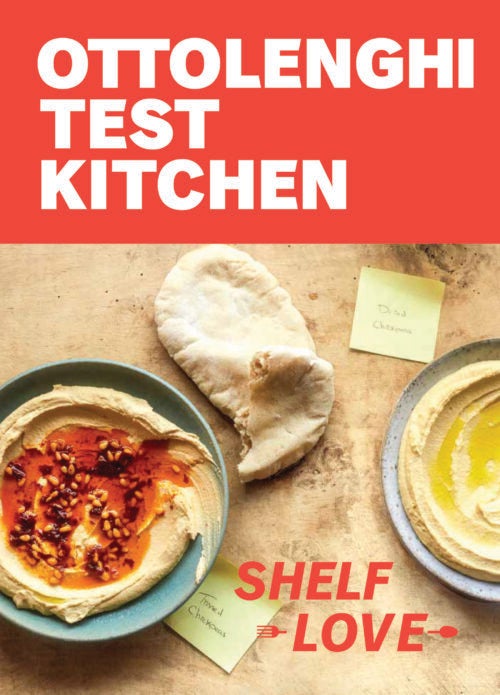

The first in a series of new cookbooks by Noor Murad and Yotam Ottolenghi reveals a few secrets about how the hummus gets made (among other pantry hits).

There are many bold ideas in the debut cookbook from the test kitchen team for Yotam Ottolenghi, the London chef with a collection of restaurants, recipe columns, packaged goods, and cookbooks. The book—Ottolenghi Test Kitchen: Shelf Love: Recipes to Unlock the Secrets of Your Pantry, Fridge, and Freezer—was dreamed up during the pandemic, and it’s filled with tips on how to Ottolenghify the frozen and the canned, the bagged and the boxed.

But the book’s biggest takeaway is that the world’s next culinary superstar is likely to be Noor Murad, Shelf Love’s primary author and the lead in the Ottolenghi test kitchen, now cleverly nicknamed the OTK. Like Ottolenghi himself—the Big Y to the OTK—Murad is gifted at bridging the gap between the flavors produced by professional kitchens and the home cook. In our recent interview, the chef talks about her hummus, her job, and how “Ottolenghi” became a verb.

My editor told me, “You have to ask, ‘How did you decide on just one hummus recipe?’” So now that I’ve read the recipe, I have some thoughts on why you chose just one, but I’ll ask you first.

Because it’s the pure one. It’s the recipe, which all recipes should be based off. It was during the first lockdown, and we were doing a lot of things on Instagram. Everyone was on social media, and that was how we kind of connected with people—by cooking. Someone asked me, “Oh, can you share a hummus recipe?” And I was like, “Yeah, you know, why not? I have time.” [Laughs at the pandemic irony of “I have time.”] Then I went through all these tips, like, “Okay, you have to do this. No olive oil. And you have to use ice. Peel the chickpeas, get rid of those skins.” And people were like, “WHHAAAT?” The funniest part is that so many people actually did that, and they’re like, “Oh my God, we can’t go back now. This is how hummus should be.”

Were those tips that you developed in the testing part of your life, or are they things you gleaned from relatives or while making hummus growing up?

I’m from Bahrain, and I grew up in the Middle East, so Middle Eastern food is not foreign to me. I just thought these were basic things that most people knew. I was like, “Yeah, of course you have to do that.” So sharing it was just pulling from what I knew and sharing that knowledge with people, which is kind of what we do at the test kitchen. We all have different backgrounds, and we’re a very international team, and we work very independently—even though we work as a group, we work independently. Everyone kind of sees through a recipe from start to finish on their own and then gets constructive feedback from people. Hummus was my contribution—I was like, “Let’s get hummus right.”

I was reading the introduction. Do you really call Yotam the “Big Y”? Like, that’s his name when he walks in the room?

Yeah, Big Y. We used to never call him that to his face. And then when I was writing the introduction, he read it, and he was like—he has very calm temperament, you know?—he was like, “Big Y. Oh, cool.”

That’s pretty funny. Now do you call him that in person?

No, I call him Yotam.

You also mentioned that, even when you were all pandemic-bound at home, you realized you could turn anything into Ottolenghi style. I was curious if you can define that. Can you put that into words?

I think, definitely, “Ottolenghi” has become a verb now: How do we Ottolenghify it? In the test kitchen, generally, any idea that we have, or anyone has, most of those ideas have been done. Sometimes it’s not such an original idea—you’re making a chicken soup, you’re making a pie. It’s been done. But we always have this conversation, at some point, where we’re like, “Okay, well, how do we Ottolenghify it? What’s the twist here? What makes it Ottolenghi?” And that can be an ingredient, a spice. It could be the way it’s plated. It could be a vegetarian take on something that isn’t. I think the cool thing about working with the team is that all of us have come from the restaurants or the delis, so we’re well-versed in that Ottolenghi language, that language of knowing what makes the dish Ottolenghi.

So you use it as a verb all the time—that’s what you say to each other?

Yeah. We say, “How do we Ottolenghi it?” Which, I mean, I don’t know how Yotam feels about that, but even he’s like, “Yeah, how do we make it Ottolenghi?”

THREE EXCITING RECIPES FROM SHELF LOVE

SWEET POTATO SHAKSHUKA

“A far cry from a classic shakshuka, yes, but we’ve found that sweet potatoes provide just the right amount of moisture and heft to serve as a base for these eggs. Serve this vibrant dish as a weekend brunch; it sure looks the part.”

ZA’ATAR SALMON AND TAHINI

“If you haven’t yet paired fish with tahini, then you’re in for a real treat. This version combines tahini with herbaceous za’atar and sour sumac, our ever familiar but much treasured test kitchen staples. We strongly recommend using creamy, nutty tahini that’s sourced from countries within the Levant. Eat this shortly after cooking, as cooked tahini doesn’t sit or reheat very well.”

STICKY MISO BANANAS WITH LIME AND TOASTED RICE (above)

“This dessert ticks all our flavor boxes—sweet, salty, tangy, and umami—and all our texture boxes—sticky, crunchy, and creamy. The bananas you use should have almost completely yellow skin, with only the tiniest bit of brown spotting.”