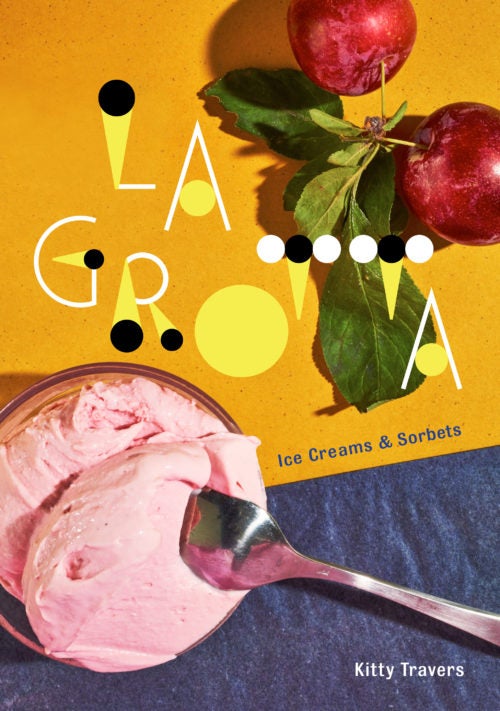

In her new cookbook, Kitty Travers gives you a taste of the London ice cream shop where she scoops flavors like pea pod, carrot seed, and guava.

One summer a few years ago, Kitty Travers received a delivery of some nectarines that were so ripe, they were close to exploding with fragrance and flavor. Her first instinct was to capture this momentary expression of perfection by turning it into ice cream, skipping the added sugar and lemon juice entirely. The resulting custard was “almost flavorless,” and Travers was, to use a British idiom, “gutted.” But she learned a valuable lesson: “Without acid and sugar, you can use the nicest fruit in the world and it won’t do anything.”

Travers has been selling inventive frozen things to a loyal cadre of London-based devotees since 2008, the year she founded her company, La Grotta Ices. On weekends, she sells her ices alongside a railway-arch fruit stand at the city’s Spa Terminus market, but she only emerges to do so in early spring once the weather is warm enough (eaten below a certain ambient temperature, ice cream doesn’t melt in the right way). She insists on making bespoke bases for specific fruits, adjusting levels of sugar and fat to best encapsulate flavor—an approach she defines as “commercially unviable, but more enjoyable.” Ice cream is fun, of course—but that doesn’t mean it can’t also be taken very, very seriously.

American ice cream lovers looking to benefit from her wisdom can rest easy: No flight to the U.K. is required. Released this month, La Grotta: Ice Creams and Sorbets is a distillation of three decades of ice-cream-making (and -eating) experience. It contains plenty of useful tips, some learned the hard way, like the time Travers had to flush away liters of lily of the valley ice cream upon realizing that it was highly poisonous. It also contains some of the zaniest flavor combinations you’ve probably encountered in an ice cream book: recipes for Pigeon Fig and Pineau des Charentes, Tomato and White Peach, or Pea Pod ice cream are the fruits of a lifetime’s obsession.

Travers scooping ice cream at La Grotta

Travers’s search for the perfect ice cream may have started by chance in Cannes nearly 20 years ago with a chance encounter with a glacière whilst waitressing, but in the ensuing decades her fascination has become all-encompassing. It was a chance inheritance from her grandmother, Mary Poppins author P.L. Travers, that started her on the path to turning this passion into a brick-and-mortar enterprise. She used the money to attend culinary school in New York; stages and jobs with the likes of Gabrielle Hamilton, Fergus Henderson, and Alice Waters followed. She left London institution St John to found her company; in its early days, everything was made at home, in two bedroom-based freezers.

The ice cream shops that have inspired her in this endeavor are dotted around the globe: Cannes, of course, but also Salvador in Brazil, Puglia in Southern Italy, and an unprepossessing place in Ostia, the “really tacky beach outside of Rome,” where they offer a pine nut flavor with the base made with toasted pine nuts (“maybe the best ice cream I’ve ever had in my life”). She is as happy to talk about American super-premium ice cream as she is Scottish white ice cream or saffron-infused Syrian ice cream with a clotted-cream base; vacation planning now starts with the ice cream and works backward from there (“It’s such a fun way of traveling around, trying ice cream wherever you go”). Simply put, Travers is endlessly, endearingly, effusively enthusiastic about her subject of choice—a simple question about her favorite fruit can result in a lengthy digression about a trip she took last year to a town on the Lombardy-Piedmont border with an “amazing” citrus collection, complete with a convoluted history involving (deep breath) a lakeside Medici villa, a garden full of prized exotica, and unscrupulous fishermen with a penchant for transporting the occasional illicit cutting back to the mainland.

The “shed” where Travers works

A decade-plus into the business, not much has changed: The ices may be made in a slightly more salubrious South London workshop these days, but global expansion is hardly on the agenda: As competitors from the U.K. and abroad have started to make their way into the London market, La Grotta has remained determinedly small in scale. Indeed, in an age of extremely online brands, La Grotta stands out for its modest digital footprint: no website, just an Instagram page with a few thousand followers, advertising the latest batch of flavors and the handful of similarly small-scale retailers where they will be sold. Quality, not quantity, is plainly at the heart of the enterprise, from the tiny “shed” in which she works (actually a converted greengrocers) to the petite scoops served (when it’s warm enough out) at the Spa Terminus concession for £3 ($4) a pop.

A love of this sort of business model seems to have been instilled in Travers almost from birth—she remembers being cycled around on the back of her father’s bicycle to his “favorite little places… little Italian delis run by old men.” Now, as an adult, she tries to make it to Italy at least once a year.

La Grotta has Italophilia baked into its very name, and Travers is quick to place the Italian way of life in opposition to how the majority of people live in her native Britain. British supermarkets, for Travers, are the great homogenizer—the antithesis of life in Italy, with its myriad regional differences, its myriad “little small family places.” It’s no surprise, really, that this is where she has found her inspiration for La Grotta: “It couldn’t be a really successful big company because everything’s [carefully] chosen, and one week I’ll have these oranges in that taste a certain way, and they might never be like that again.”

Travers has a strikingly lucid and multisensory memory for fleeting moments like this. She describes eating a perfect peach—how it “just has that smell”; how it “stings your nose a bit with the fuzz”; the true challenge of her ice cream making is to capture the whole fruit, in all these multifarious aspects: “the memory associated with the aroma and the flavor is so strong it can take you right back to where you tried it…. Each ice cream is about that little moment.” One such moment might be a glass of blood orange juice in Catania, Sicily, so vigorously squeezed that the essential oils had formed “a cream, like a cappuccino cream on top of it” and which tasted “like ice-cold strawberries and tangy oranges—incredible.” Another, closer to home, is the dairy near where she teaches in Nottinghamshire: milk like “a dream,” milk that “tastes very different to supermarket, homogenized stuff—flavors that you don’t realize we’re losing.”

La Grotta: Ice Creams and Sorbets is the logical continuation of this desire to keep things homemade—and in contrast to any number of fancy restaurant tomes currently saturating the market, here the fact that recipes will not be prepared in a professional kitchen is a feature, not a bug. The nice thing about making it at home, Travers contends, is that you get to enjoy “the best way you can ever eat ice cream”—savoring “the freshly churned texture fresh out of the bowl.” The home cook doesn’t have to use any ingredients to stabilize the ice cream over time or keep the texture scoopable at extreme textures. “You can really control it,” says Travers.

“Control” isn’t usually a word associated with ice cream, something that by its very nature is always tending toward molten chaos. But it makes a weird kind of sense when Travers says it, because keeping things close, and personal, and handmade, is such a part of who she is. Perhaps it is why she originally wanted to become an artist. “A lot of being an artist is a reaction to something,” she explains. “You might make a painting as a reaction to something, and my reaction to plants and Italy is to make an ice cream. That’s my way of being an artist, I suppose. Going to art school, I knew I was interested in stuff like that, but this is the combination of taking what I really like and spitting it out the other end—and it happens to be edible.”

Ingredients

- 375 grams fresh apricots

- 150 grams sugar

- 170 milliliters whole milk

- 170 milliliters double cream

- 3 egg yolks

- 1 teaspoon honey (optional)

A few years ago, late at night in bed and high on Italian eBay, I bought several thousand pounds’ worth of 1960s Italian ice cream machinery from a used-catering-equipment salesman in northern Italy. I hired a van and undertook an insane 24-hour drive to Turin and back to bring the two-ton machines back to the U.K. Once home, they sat, unfixable, in storage for approximately six years, quietly leaking thick black oil and defunct coolant over my garage floor until I sold them for scrap metal last summer.

The upside to this story was that en route home we stopped at a market in Lyon, where I took advantage of every bit of negative space in the van and bought a stall’s entire stock of very ripe apricots to bring back with me. It made enough ice cream for that whole summer, it was extraordinarily good — the delicious but slightly poisonous marzipan flavor of the noyau, or kernels, acting as a bitter reminder to avoid late-night eBay purchases.

- To prepare the ice cream: Slice the apricots in half and remove the stones; keep these to one side. Cook the apricot halves very lightly just until the fruit collapses. If using a microwave, place the fruit in a heatproof bowl with a tablespoon of water. Cover the bowl with cling film and cook on high for 2-3 minutes until tender. Otherwise simmer the apricot halves gently in a nonreactive pan, just until they are cooked through and piping hot (do not boil). Cool in a sink of iced water, then cover and chill in the fridge.

- Place a clean tea towel on a hard surface, then line the apricot stones up along the middle of the towel. Fold the tea towel in half over the apricot stones to cover them and then firmly crack each stone with a rolling pin (the tea towel prevents bits of the shell from flying all over the kitchen.) Try to hit hard enough to crack the shell, but not so energetically that you completely obliterate it—you want to be able to rescue the kernels from inside the shell afterward.

- Pick the tiny kernel from each shell, then grind them in a mortar and pestle with 20 g of the sugar.

- Heat the milk, cream, and the ground kernel mix in a pan, stirring often with a whisk or silicone spatula to prevent it catching. As soon as the milk is hot and steaming, whisk the yolks with the remaining sugar and honey (if using) until combined.

- Pour the hot liquid over the yolk mix in a thin stream, whisking constantly as you do so, then return all the mix to the pan. Cook gently over a low heat, stirring all the time, until the mix reaches 82°C. As soon as your digital thermometer says 82°C, remove the pan from the heat and set it in a sink full of iced water to cool—you can speed up the process by stirring it every so often. Once entirely cold, pour the custard into a clean container, cover, and chill in the fridge.

- To make the ice cream: The following day, use a spatula to scrape the chilled apricots into the custard, then blend together with a stick blender until very smooth—blitz for at least 2 minutes, or until there are only small flecks of apricot skin visible in the mix. Using a small ladle, push the apricot custard through a fine-mesh sieve or chinois into a clean container, squeezing hard to extract as much smooth custard mix as possible. Discard the bits of skin and kernel.

- Pour the custard into an ice cream machine and churn according to the machine's instructions, usually about 20-25 minutes, or until frozen and the texture of whipped cream.

- Transfer the ice cream to a suitable lidded container. Top with a piece of waxed paper to limit exposure to air, cover, and freeze until ready to serve.

Ingredients

- 400 grams very fresh peas in their pods

- 400 milliliters whole milk

- 150 milliliters double cream

- small pinch of sea salt

- 4 egg yolks

- 130 grams sugar

In 2009, I was asked to make an ice cream to sell at the Art Car Boot Fair in London’s Bethnal Green. The theme that year was “recession special.” There were a lot of “credit crunchy” kind of flavors going on among cake bakers, but I wanted to try to make a cheap milk ice out of pea pods (pods are popping with sweet fresh flavor but are usually thrown away, and that seems a shame). I billed it as 100p ice cream and sold scoops for a pound a pop. It went down a storm, and I still make it now in the summer—albeit a slightly more costly custard version. It’s delightful served with fresh strawberries or Garriguette Strawberry ice cream on the side, plus a sprinkle of sea salt flakes.

- To prepare the ice cream: Wash the peas in their pods and then pod them, reserving the pods. Blanch the fresh podded peas in boiling water for 30 seconds and then refresh them in iced water to preserve their color; drain and put them in the fridge, covered.

- Heat the milk, cream and salt together, stirring occasionally. As soon as the liquid reaches simmering point, add the pea pods and simmer them for 3 minutes. Remove the pan from the heat and blitz the pods and liquid with a stick blender for a minute. Strain the mixture through a sieve, squeezing hard on the pods to extract as much flavor from them as possible. Discard the blitzed pea pods.

- Wash the pan and pour the fragrant milk-and-cream mixture back into it. Bring to a simmer. Stir often using a whisk or silicone spatula to prevent it catching. Once the liquid is hot and steaming, whisk the egg yolks and the sugar together in a separate bowl until combined.

- Pour the hot liquid over the yolks in a thin stream, whisking continuously. Return all the mix to the pan and cook over a low heat until it reaches 82°C. Stir constantly to avoid curdling the eggs, and keep a close eye on it so as not to let it boil. As soon as your digital thermometer says 82°C, place the pan into a sink of ice water to cool. Speed up the cooling process by stirring the mix every so often. Once the custard is at room temperature, scrape it into a clean container, cover with cling film, and chill in the fridge overnight.

- To make the ice cream: The following day, add the blanched peas to the custard and liquefy with a stick blender for 2 minutes, or until it turns froggy green. Use a small ladle to push the mixture through a fine-mesh sieve to ensure it is perfectly smooth.

- Pour the custard into an ice cream machine. Churn according to the machine's instructions, usually about 20-25 minutes, or until frozen and the texture of whipped cream.

- Scrape the ice cream into a suitable lidded container. Top with a piece of waxed paper to limit exposure to air, cover, and freeze until ready to serve. Eat within a week.

Ingredients

- 1 vanilla pod

- 350 milliliters whole milk

- 170 milliliters double cream

- pinch of sea salt

- 5 egg yolks

- 45 grams sugar

- 40 grams light brown muscovado sugar

- 20 grams malt extract

- 30 grams black malt

Black malt is the name given to roasted grains of malted barley—traditionally the grain used in the brewing industry to make porter (and, as a consequence, easily available online for the home brewing crew). Steeped overnight in an egg custard base, it produces a creamy, biscuit-colored ice cream with rich complex toasted coffee and nut flavors, which are enhanced by thick malt syrup and vanilla bean. It’s a real spoon-licker. Serve with Banana, Brown Sugar & Rum ice cream, if you like.

- To prepare the ice cream: Split the vanilla pod lengthways and scrape out the seeds, adding both the seeds and pod to a nonreactive pan along with the milk, cream, and salt. Bring the mixture to a simmer, stirring often, using a whisk or silicone spatula to prevent it catching. Once the liquid is hot and steaming, whisk the egg yolks, sugars, and malt extract together in a separate bowl until combined.

- Pour the hot liquid over the egg mix in a thin stream, whisking continuously. Return all the mix to the pan and cook over a low heat until it reaches 82°C. Stir constantly to avoid curdling the eggs and keep a close eye on it so as not to let it boil. As soon as your digital thermometer says 82°C, remove from the heat and stir the grains of black malt into the custard. Place the pan in a sink full of ice water to cool, stirring the mix occasionally to speed up the cooling process. Once cold, cover with plastic wrap and chill in the fridge.

- To make the ice cream: The following day, use a small ladle to push the custard through a fine-mesh sieve or chinois. Squeeze hard to extract as much toffee-colored custard from the malt as possible. Discard the malt and keep the vanilla pod to rinse and dry later, then liquefy the custard with a stick blender for a minute until smooth.

- Pour the custard into an ice cream machine and churn according to the machine's instructions, about 20-25 minutes, or until frozen and the texture of whipped cream.

- Transfer the churned ice cream to a clean, lidded container. Top with a piece of waxed paper to limit exposure to air, cover, and freeze until ready to serve.