Even if you know about his most famous discovery, chances are you don’t know anything about Frank N. Meyer.

Most Americans don’t recognize the name Frank N. Meyer, but many are familiar with the fruit that bears his name. The Meyer lemon is a specialty-citrus sensation. Just ask Martha Stewart, who has more than 100 Meyer lemon–specific recipes and related content on her website. Or the U.S. Postal Service, which in January officially enshrined the fruit’s special place in American culture with the unveiling of the two-cent Meyer lemon stamp.

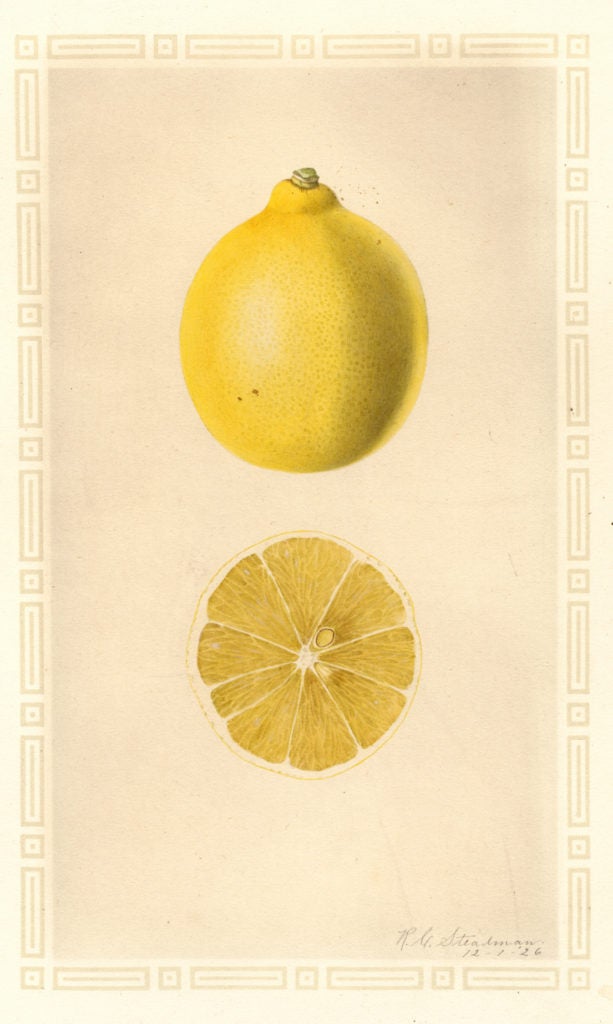

Long thought to be a simple lemon-orange hybrid, the Meyer lemon is now believed to be a cross between three of the original citrus species—citron, mandarin, and pummelo—based on a 2016 genetics study led by French scientist Franck Curk.

The unique orange-tinted lemon has a higher sugar-to-acid ratio than the average waxy yellow supermarket variety, making it especially well suited for cakes, pies, and pastries galore. “It has more sugar, it has more juice, and it has that distinctive flowery character that dessert chefs really love,” says grower Lance Walheim, whose company, California Citrus Specialties, was among the first large-scale suppliers of the Meyer lemon, beginning in the mid-1980s.

In California, where it flourishes, ripening in the Central Valley generally from November until March and even year-round along parts of the coast, the Meyer lemon is emblematic of the local foodways. That close association can arguably be traced to Berkeley’s famed Chez Panisse, where California Cuisine pioneers Alice Waters and Lindsey Shere showcased the fruit in numerous recipes and played up its local roots. “Although common in California backyards, they are just beginning to be commercialized,” Waters wrote in 1999’s Chez Panisse Cafe Cookbook. “Ask your friends or relatives in California to send you some.”

The Meyer lemon, of course, is not native to California. It came from China, specifically the tiny village of Fengtai, near Peking. That’s where Frank N. Meyer, one of the first Westerners to trek across China’s vast interior, noticed it back in 1908; the short potted plant produced a notable amount of fruit for its size. “The fruit is large, very smooth, and thin skinned, very juicy, only slightly sour, and is practically seedless,” Meyer wrote of the discovery. He also discovered that wealthy Chinese would pay as much as $10 for a single fruit-bearing tree. If that was the case, he figured, then perhaps one day wealthy Americans would do the same.

It was his job to think about such things: Meyer worked for the U.S. government as an “agricultural explorer,” traveling across Asia in search of better food, like some early-20th-century Anthony Bourdain. The fancy lemon that bears his name is one of some 2,500 types of plants—including multiple varieties of peach, pear, plum, and persimmon, to mention only a few of the p’s—that Meyer picked up during his four long missions to the Far East, braving all kinds of harsh conditions and violence along the way.

Meyer was something of a celebrity back in his day: Major newspapers chronicled his exploits and printed dashing portraits of the full-bearded explorer sporting his trademark sheepskin coat, hunting boots, and walking stick. The Washington Post once called him “the Agriculture Department’s Christopher Columbus,” while the Los Angeles Times praised him for “doing the impossible, getting along in impossible places and with impossible people.”

But Meyer’s extraordinary life was also relatively brief: It ended tragically in 1918, when the 42-year-old explorer vanished from a ship en route to Shanghai. A fisherman later found his body floating in the Yangtze River.

One hundred years after his death, Meyer is a forgotten hero in the country he gave his life to provide with bountiful never-before-seen consumables. But his once-obscure lemon has become a cultural icon, lending its floral scent and mellow flavor to everything from gourmet desserts to beauty products. It’s perhaps a fitting legacy for Meyer, an eccentric plant lover who believed in reincarnation. But it’s also a fragile one. Despite its recent popularity, the Meyer lemon is now in danger of falling victim to its own success, much like the man who discovered it.

Frank Meyer might not be considered a Founding Father in the pantheon of American food heroes, but he played a fascinating role in the sweeping transformation of the U.S. food system and the government’s active efforts to make that happen.

Consider, for example, Meyer’s work with the soybean. The now-lucrative legume was hardly considered a crop in the explorer’s day: According to the USDA, there were fewer than a dozen varieties in cultivation when Meyer first landed in China in 1905. Over the next three years, he collected 42 new types of soybeans on his way through the Ming Tombs Valley, Manchuria, Mongolia, Korea, and Siberia. Those early specimens provided genetic material for the USDA’s first large-scale soybean program at Arlington Farm Experiment Station in Virginia, located where the Pentagon now stands. America’s booming soybean industry—a total crop valued at $41 billion in 2016—literally grew from there.

Meyer did more than just pick up some soybeans (over 100 different varieties throughout his 13-year career); he was also an early advocate for soy as a food source for humans, not just livestock. Meyer paid strict attention to how the Chinese used soybeans to make different protein-rich foods, like soy milk and tofu, which he called “bean cheese.” His photographs of large blocks of fresh-made tofu and baskets full of bean sprouts are among the earliest on record. He even sent samples of fermented tofu to his bosses back at the USDA, though his enthusiasm was tempered by low expectations. “I must admit that it will take some time for the white races to acquire the taste of the very large majority of these products,” he wrote of what is now a $4.5 billion industry in America alone. “He introduced Americans to all kinds of foods that they never heard of before and took pictures of the Chinese making those foods,” says William Shurtleff, founder and director of the California-based Soyinfo Center, who has cited Meyer’s work in numerous publications on soy and soy products. “Many of Meyer’s photographs are priceless.”

Meyer was one of a half-dozen explorers scouring the globe for new and hardier things to grow under the direction of long-serving agriculture secretary James Wilson. Their combined efforts yielded a lot of what we eat today, including avocados, figs, and mangoes. But Meyer’s unique personality, combined with the tremendous difficulty of his assignment, made him the group’s media darling and arguably the favorite of his boss, David Fairchild, head of the USDA’s Office of Foreign Seed and Plant Introduction.

“Even during his lifetime, [Meyer] was the star,” says Amanda Harris, an investigative reporter whose 2015 book, Fruits of Eden: David Fairchild and America’s Plant Explorers, chronicles the efforts of Meyer and his globe-trotting contemporaries. “When he went off on a big voyage, Fairchild made sure that The Washington Post wrote a big story about him.” In 1908, Fairchild encouraged his star explorer to meet with then president Theodore Roosevelt, who later used Meyer’s photos of deforestation in China to push for greater conservation efforts in America. “He used his pictures, and he mentioned Meyer’s name,” says Harris. “Imagine walking by yourself through China in incredibly bad conditions. Then you’re suddenly sitting around with the president of the United States sharing anecdotes—that’s a heady contrast.”

Born in the Netherlands in 1875, Frans Nicolaas Meijer was by all accounts kind of a weird dude: a loner and wanderer whose love of nature sometimes veered toward mysticism.

“He used to think that plants talked to him,” says Harris, who notes that Meyer had once lived in a Thoreau-inspired Utopian colony in Holland, growing vegetables for his fellow transcendentalists. Multiple histories, including Fruits of Eden and the more comprehensive 1984 biography Frank N. Meyer: Plant Hunter in Asia, make note of the explorer’s apparent belief in reincarnation, perhaps not surprising for such a close observer of vegetal life cycles. Meyer made references to past and future lives in his many letters from afar.

A former protégé of world-renowned Dutch botanist Hugo De Vries, Meyer had worked as an immigrant gardener at USDA facilities in California and Washington, D.C., before his reputation for walking excruciating distances—most notably, a 14-day, 260-mile solo trek across Mexico—earned him the assignment of a lifetime. In the 1935 memoir The World Was My Garden, David Fairchild recalled his first interview with Meyer, noting the sweaty, shabbily dressed Dutchman’s “lack of pose, his willingness to work for any reasonable sum, and his evident passion for plants.” He added that Meyer’s “eyes filled with tears” when discussing a neglected bamboo plant that had died.

With his botanical smarts and restless spirit, Meyer appeared to be the perfect candidate for a trip to China, then a sprawling land of over 3.5 million square miles of diverse terrain with at least 200 different languages (none of which Meyer could speak) and mainly primitive forms of transportation. “There were no roads; there were no maps,” says Harris, adding that rural China could be a particularly dangerous place for a white man: In the wake of the Boxer Rebellion, when violent Chinese nationalists tried to drive all foreigners out of the country, xenophobia remained strong in some places. Yet the potential for discovery was huge: The Chinese had been farming for thousands of years, cultivating all kinds of fruits and nuts, even in harsh climates.

Back then, most Western travelers to China rode around in servant-carried sedan chairs. Meyer preferred to walk, usually with very little company: a guide, an interpreter, and occasionally an assistant. For protection, he carried a loaded revolver and a bowie knife. The blade came in handy during an attempted mugging in Siberia, when Meyer stabbed one thug in the belly, sending his attackers scurrying. The incident later made the newspapers, enhancing the explorer’s mystique.

In her book, Harris notes that Meyer wore out three pairs of boots during that first mission to Asia alone, returning to America with shoulder-length hair and “fingernails curved backwards in the style of a Mandarin.” He also came back with his now-famous find: the Meyer lemon, which he originally called the wildly less marketable “dwarf lemon.” He had stumbled upon the peculiar fruit after nearly three long years combing through farms, forests, mountains, and deserts. His future legacy, by contrast, was growing in a pot in a residential doorway. Meyer appreciated its practicality, writing: “The idea is to have as many fruits as possible on the smallest possible plant.”

Of all the consumables that Meyer could be remembered for—in fact, many plant species now bear the Latin name meyeri, the explorer’s botanical signature—the Meyer lemon is an ironic pick. “He went looking for things so systematically,” says Harris, “and then the one thing that made him somewhat celebrated was kind of accidental. He just threw it in as an afterthought.” Meyer himself seemed less taken with the lemon than with other Asian fruits, like peaches and persimmons. In his only published manuscript, he devoted just two brief paragraphs to it. But shortly before Meyer’s death, his boss, David Fairchild, raved about the dwarf lemon “winning favor wherever it goes” back in the States.

Meyer was so good at his job that the USDA sent him back to Asia three more times. He remained the same rugged individualist throughout. “On the one hand, it made it easier to work alone like that,” says Harris. “On the other hand, I think it was one of the things that killed him.”

On his final trip, Meyer set out for South China with a big botanical shopping list that just kept getting bigger. In April 1917, his bosses sent an urgent request for 100 pounds of poppy seeds in order to make morphine for U.S. forces heading into World War I. “This telegram puzzles me somewhat,” Meyer replied. He reminded his bosses that poppy cultivation was a deadly offense in China, where, he noted, “farmers have been beheaded who had it in their possession” and, moreover, Chinese soldiers had previously threatened to execute him on mere suspicion of being an opium smuggler. “Only in the most out of the way mountainous places of Szechuan, Kansu, Yunnan and Hupeh one possibly could get hold of a few ounces here and there,” Meyer wrote, “but a hundred pounds! Ah, that would be something!”

An online transcript of Meyer’s correspondence during that final mission shows a man gradually succumbing to the loneliness and intense pressures of his job. On June 1, 1918, Meyer and his interpreter were traveling aboard a steamer bound for Shanghai. A crew member saw Meyer leave his cabin that night; whether he fell overboard or leaped to his death remains unclear. When American officials recovered his body, there were no signs of foul play. His face was too far gone for positive identification, but the U.S. consul recognized his clothes and his beard.

If it seems odd that a man of letters would take his own life but not leave behind a suicide note, Harris has some thoughts. “You could read some of his last letters as suicide notes,” she says. “There’s a lot in there about ‘Why should I go on?’ Everything was going wrong for him.”

But why would the swashbuckling botanist take his own life? Well, it seemed like a lot of Meyer’s hard work was going to waste. New import restrictions, enacted amid rising anti-foreign sentiment in Washington, tied up a lot of Meyer’s seeds and cuttings in transit. A hurricane that swept through Texas wiped out many others. Lonely and weary from his wanderings, frustrated to see his hard work ruined, and disillusioned with a world at war, the explorer had a somewhat bleak outlook. In his final letter to Fairchild, Meyer wrote: “Times certainly are sad and mad and from a scientific point of view so utterly unnecessary.”

The ballad of Frank Meyer would be pretty depressing and totally lost on modern audiences if not for the unexpected rise of his namesake lemon more than a half-century later.

“Particularly here in the Bay Area, people are always very interested to hear the story of Frank Meyer, because you’re dodging Meyer lemons left and right,” says Robin Sloan, an Oakland-based author whose 2017 novel, Sourdough, includes a brief but memorable passage about Meyer and his lemon. “That’s his ticket back into public consciousness, that this random namesake has become a symbol in our food culture.“

It almost didn’t happen. Before he died, Meyer got a glimpse of the future when he saw his Chinese lemon trees thriving at an experimental USDA garden in Chico, California. Thankfully, he didn’t live long enough to see them get destroyed. In the 1940s, after the Meyer lemon tree was discovered to be a carrier of the tristeza virus, it was largely banned in order to protect other produce. It wasn’t until the 1970s, when the University of California began distributing budwood for a virus-free version, the so-called “Improved Meyer lemon,” that the fruit began to truly take root in the Golden State. “Everything now legally has to come from clean sources,” says Tracy L. Kahn, Ph.D., curator of the Citrus Variety Collection at the University of California, Riverside, who notes that the Meyer lemon has a much older Chinese name (xiangningmeng) and probably existed for thousands of years before Meyer discovered it.

Beginning in the mid-1980s, sudden culinary interest in the fruit turned it into a marketable commodity for growers like Lance Walheim. “We knew that Lindsey Shere and Alice Waters were using them at Chez Panisse,” says Walheim. “They were just picking them out of people’s backyards.” (When Shere published Chez Panisse Desserts in 1985, it included recipes for Meyer lemon meringue pie, Meyer lemon ice cream, Meyer lemon sherbet, Meyer lemon soufflé, and Meyer lemon mousse.)

Walheim’s company, California Citrus Specialties, was among the first commercial suppliers and eventually one of the state’s largest, with about 800 Meyer lemon trees. For a long time, business was booming. “We were making really good money on the Meyers as recently as five years ago,” Walheim says. More recently, though, a lot of other companies have tried to cash in on the fruit’s cult following; even big-name brands like Sunkist are now marketing Meyer lemons. As a result, the rising supply is outpacing demand. “The market is flooded, so prices have dropped,” Walheim says. “We’re at the point now where we’re considering taking some Meyer lemons out because they’re not worth it anymore.”

Mainstream commercial success has so far eluded Frank Meyer’s dwarf lemon from Peking, stifling the explorer’s own comeback in the popular imagination. “Even with their popularity, Meyers represent a small percentage of lemon sales annually, with standard varieties like Eureka dominating the category,” according to a statement from organic grocer Whole Foods Market. Last month in New York City, California-grown Meyer lemons were selling at Whole Foods locations for $2.99 per pound—50 cents less than conventional blood oranges. A posted sign described the Meyer lemons’ “honey-floral taste” but made no mention of Meyer himself.

“It’s still a very specialty, very niche market,” says Joe Berberian, sales manager at California-based Bee Sweet Citrus, Whole Foods’ chief supplier of Meyer lemons. “We always say that if you plant one tree too many, it’ll crash the market, and that’s basically what happened with Meyer lemons in California.” Berberian adds that over the past decade, prices for “the Cooking Lemon,” as it’s described on his company’s packaging, have fallen from between $22 and $25 for a typical 18-pound box to the current $10 to $12 per box.

“It’s a fantastic piece of fruit,” Berberian says. “I wish more people knew about it.”

The same could be said of Meyer himself.