The prolific illustrator is a master of whimsy and wit, finding beauty in the mundane, and—with a new book—the drawing of cakes.

“What do you suppose a sneak is?” Maira Kalman is bent over an image from the previous day’s New York Times, which she has cut out and affixed to the fridge the way one might a yoga schedule or a wedding invitation. It shows ten portraits of 19th-century criminals. George Lockwood, with a handlebar moustache and a dazed countenance, is wanted for being a “burglar and a sneak.” John Cannon (“left eye watery; large nose,” according to period police notes) is a known hotel thief. Kalman, a prolific illustrator whose oeuvre ranges from iconic New Yorker covers to children’s literature to an illustrated edition of Michael Pollan’s Food Rules, studies the photos with delight, filing the faces away for some as-yet-unknown future use.

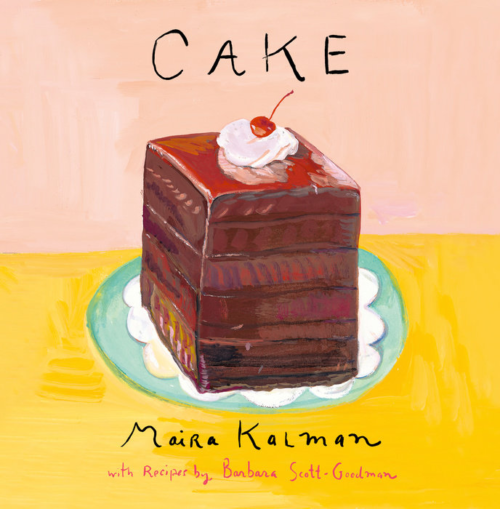

I’m sitting in Kalman’s Greenwich Village living room, eating lemon chiffon cake and examining vintage mugshots, because she has recently completed a book about cake called, simply, Cake. It arrived on my desk in January, amid the usual stream of keto dieting manuals (the diet of the moment), vegan dessert books, and collections of 30-minute Instant Pot meals. Only Cake, a compact, richly illustrated recipe volume about the size of a kitchen trivet, won me over immediately.

Take as an example a recipe for pistachio and almond pound cake. Rather than the ordinary photograph of a proud, burnished specimen, or perhaps a close-up of its even crumb, Kalman paints a man and three women seated on a leafy terrace, scowling at the viewer, arms crossed, seemingly annoyed to have been interrupted. On the table somewhere, amid coffee cups, is a small yellowish-brown smudge: the pound cake.

“When I think about pound cake I think about people who play bridge, and they have a slice of cake,” Kalman muses when I ask her about it, by way of an explanation. “Or women who go in the afternoon and smoke cigarettes and they’re not nice—they say very nasty things about themselves or other people—and that kind of cake is there.”

To understand my enthusiasm for this delightfully offbeat tableau, it helps to know that I am a very badly behaved baker. I do not level off cup measures of flour; I do not wait for butter to come to room temperature before mixing; I rarely sift when told to do so. I know that I should, but honestly I can’t bring myself to do it. Everything ends up tasting delicious despite my small acts of rebellion, and I think my lopsided cakes, my squat little banana breads with their underbaked middles, are beautiful in their own misfit sort of way.

Given all this, I find the average cake cookbook—with those exacting volume and mass measurements, exhaustive instructions, and most of all, glossy shots of precisely rendered confections—to be not just boring but oppressive. What a relief to discover one where the knobby, eccentric cakes in the pictures look like the ones I make.

Cake is Kalman’s second book-length foray into the world of food—following that collaboration with Pollan in 2011—but over the course of more than three decades, she has produced 28 volumes, from an illustrated version of Strunk & White’s The Elements of Style to a series of children’s books inspired by her beloved dog, Pete. Kalman’s style is saturated with color and pseudo-childish—think Saul Steinberg meets David Hockney—and she is masterful at capturing, with whimsy and wit, the beauty in mundane moments and things. Among the illustrations in The Principles of Uncertainty, her best-selling book about the search for meaning in life, are a pleated green skirt, a sidewalk with a bucket and shoes, and a bowl of tomato bisque.

When it comes to cake, Kalman’s interest in the food itself is not so much culinary as conceptual. Cakes accompany gatherings, conversations, times of sadness, and times of joy, she tells me. Her illustrations occupy themselves with telling these stories, many of which are autobiographical, memories from a childhood split between Tel Aviv and the Riverdale section of the Bronx. In one, a young girl in pigtails and two women gather on a terrace over cake. “If you go to visit an elderly aunt in a crisp dress (who earlier had hauled the wet laundry up to the roof to hang and dry), she will serve you cake that she made at dawn,” reads the handwritten text accompanying it. “No doubt about that. Cheesecake or honey cake or fruitcake. Then you can tell her your troubles and she will offer sage advice. Usually. But not always. She is human, after all.” The cake in the picture, a naively rendered Bundt shape, might be any of those three. What matters, Kalman seems to say, is that there is cake at all.

Kalman, as it happens, loves to eat cake but doesn’t particularly enjoy making it. Cake’s 17 recipes come not from her but courtesy of the cookbook writer Barbara Scott-Goodman. Kalman and Scott-Goodman have run in the same circles for 30 years and came up with the idea for Cake when they saw each other at a cocktail party. “Who would say no to doing a book about cake?” she says of the decision, and I understand completely.

The two made a list of their favorite cakes and asked around among friends: What cakes do you love? What cakes do you remember? What do you think is iconic? The recipes needed to be within the grasp of the average home cook. The final list, Kalman said, is meant to “describe the texture of an average life.” There is cheesecake, coffee cake with streusel, honey cake, gingerbread cake. Scott-Goodman’s recipes are brief, direct, neither fussy nor technical. One mostly stirs, dumps, and bakes.

My favorite illustration in Cake happens to be the one for Kalman’s favorite: lemon pound cake. In it, Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas sit at a banker’s desk, Stein bent over a diary, Toklas with her hands folded in her lap (Stein and Toklas are the only recognizable historical figures to appear in Cake aside from a portrait of the ballerina Anna Pavlova, floating en pointe, that accompanies Scott-Goodman’s recipe for pavlova with fresh berries). A lemon pound cake awaits, untouched. The handwritten caption reads, “Every Sunday they ate a lemon pound cake and make plans for the week.”

Kalman based the illustration on one of her favorite photos of the two women, adding the pound cake into the frame. She imagines that Toklas would have made a simple sweet like this to go along with their discussions. The scene is pure Kalman: not so much an endorsement of this cake’s particular virtues as an appreciation of life’s quiet rituals. I’ve never wanted to make a pound cake so much in my life.