Zoe Adjonyoh makes the case for seeking out red palm oil, smoked barracuda, and spicy West African kpakpo shito chiles.

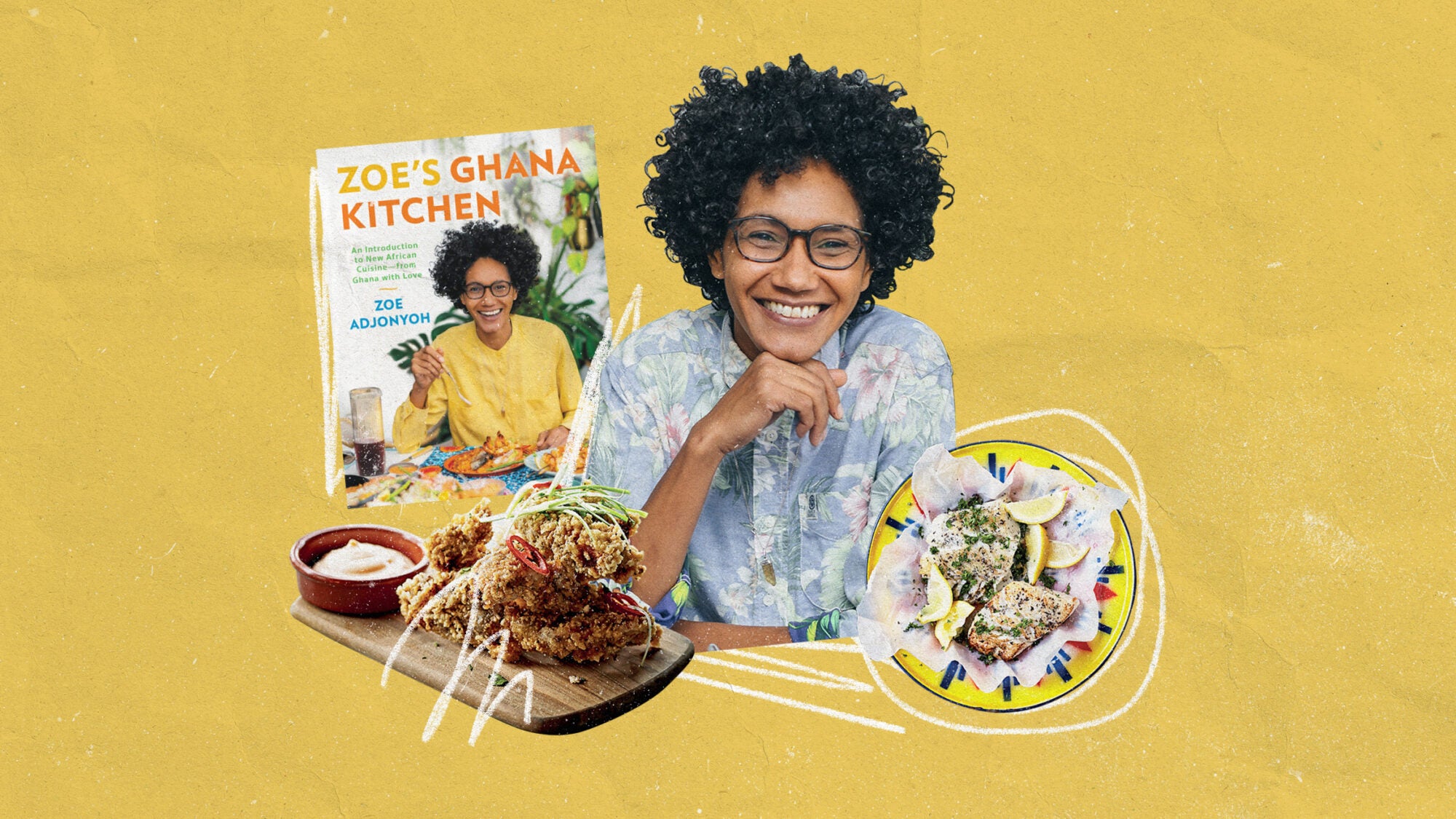

Chef and writer Zoe Adjonyoh originally published her cookbook, Zoe’s Ghana Kitchen, in 2017, bringing a flurry of jollof fried chicken, fiery shito, and okra soup into UK kitchens. A lot has changed in the four years since. Adjonyoh has moved from London (where she ran a restaurant and taught frequent cooking workshops) to New York, and the American publication of the book this fall comes at a time when there’s more global excitement about Ghanaian cuisine than ever before.

We sat down to talk about the ever-evolving food scene in Ghana’s capital, Accra; some of the make-or-break ingredients in Ghana’s most essential dishes; and why there are certain dishes that you should eat either spicy or not at all.

You originally published Zoe’s Ghana Kitchen in the UK in 2017. What made this year a great time to republish it in the United States?

The publisher felt, and I agree, that there is a huge market in the States for people in the diaspora connecting with their roots and ancestry. It’s a moment in time when there’s been more of a breakthrough for West African cuisine. There’s definitely been an upswing in people reconnecting with their culture—cooks and chefs in particular—and using their ancestry as a way to communicate their creativity.

What’s changed in terms of the actual food scene in Ghana? What’s happening in the restaurant scene, and what’s new and exciting?

There are lots of exciting things happening. There’s a lot of new dining concepts in Accra. Ghana had the Year of Return a couple years ago. It was a big callout throughout the diaspora to come back to Ghana. That brought a lot of money and investment and wealth, but there were also an increasing number of people, who were probably second-generation Ghanaians, who’d gone back to open businesses there. It’s that synchronicity of timing. Chefs like Selassie Atadika, Nana Araba, Kess Eshun, Fatmata Binta, Eric Adjepong, have all been gaining profile in their respective planes, and that’s inspiring to a lot of young cooks and chefs.

When I went back to Ghana in 2018, after the book came out, I was really surprised that I had fans in Ghana. People knew who I was, they were really big fans of the book, and they were cooking from it and starting businesses inspired by it. I’m not sure if this is a good or a bad thing, but fusion cooking is everything right now in Accra. When you go to any of the local eateries, everyone wants to do fusion food—celebrating Ghana but presenting it in a more Western style. I’m not entirely sure that even counts as fusion.

The most common question in the world is, “Is it spicy?”

It’s so cool to see what a role seafood plays in the book. Are there particular types of fish or seafood that are important to Ghanaian cuisine that are tough to find in the UK?

Tilapia is huge in America, but it wasn’t so in the UK, and it was very much something you found in African grocery stores or Indian grocery stores. I think that’s becoming a little bit more available and mainstream now.

One fish that I’m not even a huge fan of, but that’s very common, is perch. It’s a bit like catfish. They’re not my favorite fish, but those would be the ones that were harder to find because they’re more localized.

Maybe barracuda. But a lot of the time, the seafood would be smoked and dried. It’s eaten fresh on the coast, but for preservation purposes, most fish is immediately smoked and dried, so it’s easy to then export it. So you can get all of the herring and barracuda in New York, and in lots of places in America.

You write in the introduction about trying to balance tradition with a sense of experimentation with Ghanaian ingredients and flavors. Are there any dishes in the book that felt too sacred to riff on, where you felt like you had to keep your own personal interpretation pretty close to home?

I think, when I wrote that, I was trying to reference the importance of being able to have a relationship with whatever is traditional. There are certainly dishes, like okra soup—you can’t really mess about with that too much. Things like pepper soup or light soup, there’s a definite profile that you have to keep.

The most common question in the world is, “Is it spicy?” And it’s like, well, what do you mean when you’re asking that? Are you asking if it’s hot? Because “spicy” means many, many things. I’ve always thought that heat is a seasoning, so when you’re using anything that’s a hot spice, you should use it to your taste. Except, there are certain dishes that are hot dishes, and they need to come hot. And if you don’t like hot food, don’t mess with it, don’t cook it.

Even something like red red. People say they can’t get ahold of red palm oil (I think they’re just not trying very hard). I will give permission to deviate from using red palm oil if people want to. But then it’s like, you’re not really making red red anymore. You have permission to bury the recipe, and you’ll have a delicious bean stew, but it’s not going to be red red anymore.

TWO EXCITING RECIPES FROM ZOE’S GHANA KITCHEN

Pan-Roasted Cod Seasoned with Hibiscus

Fruity hibiscus salt pairs with nutty grains of paradise in this quick, stovetop cod recipe.

Jollof Fried Chicken

A street food staple that packs a punch from a jollof spice mix full of ginger, paprika, cinnamon, and crayfish powder.