Japanese yōshoku loaves, a product of the lean postwar Occupation Era, has ignited a nation’s obsession with toast.

The Japanese are big on toast. I first discover this, empty plate in hand, groggy with jet lag, while waiting for one of those Rube Goldbergian conveyor toasters to deliver, at an excruciating pace, a single slice of honey-hued bread—in the process causing a polite pileup as other guests wait their turn at the first and oldest breakfast buffet in the country. Since 1890, the kitchen staff at Tokyo’s Imperial Hotel has artfully arranged encyclopedic displays of both Western and Japanese dishes at its Viking Sal restaurant—the seemingly incongruous name channels the bounty of smorgasbord—including cherry Danish, fluffy pancakes, bacon and sausage links, potato salad, smoked salmon, salty pickles, roasted seaweed, miso soup, “hot spring” eggs, rice porridge, dried plums, and for those of us whose appetites are not fully adjusted to the time zone, a dessert station that would make a Parisian pâtissier weep.

And I skip past all of that for plain toast.

Japan has a long history of adapting and elevating imported food traditions: the term yōshoku refers to any Western-style dish that has been assimilated for the local palate. Bread has been consumed in some form or another since the 16th century, after the first Portuguese and Dutch trading ships landed at Nagasaki. (In Japanese, bread is called “pan,” a variation of the Portuguese word pão.) When Japan subsequently closed its borders a century later and attempted to purge foreign influences, eating bread fell out of vogue until the outbreak of the first Opium War (1839–1842). At that time, and out of pure necessity, a high-ranking samurai employed a basic hard-baked loaf as field rations for his troops, but unsurprisingly it was as appetizing as British Navy hard tack.

Bread regained general popularity in 1874 with the creation of anpan, a natural rice yeast roll filled with sweet adzuki bean paste, by pioneering baker Yasube Kimura. (Kimuraya bakery still sells anpan at its original location in Tokyo’s Ginza district.) Other yeast buns followed, including melon pan, with a meringue-like topping, and cream pan, invented by Nakamurya baker Aizo Soma, inspired by cream puffs or choux à la crème in 1904.

But the squishy white sandwich loaves beloved of American GIs has proven to be the most unlikely cross-cultural phenomenon. Instituted during the lean postwar Occupation Era—when commercial bread baked with imported wheat and powdered milk became a cheap dietary substitute—a generation of Japanese children ate school lunches featuring slices of the standard square loaf they renamed shokupan, literally “food bread,” and a dome-shaped Pullman loaf, or igirisu-pan. Both have a fine crumb interior, with crusts somewhere between muffin top and croissant in texture. These yōshoku loaves have become an object of obsession, and because the Japanese can take any obsession to the extreme, humble toast is a lovely expression of their fascination with an industrialized food we often take for granted.

At Centre the Bakery in Ginza, customers can choose between many toasters to use.

Yukari Sakamoto, author of Food Sake Tokyo, explains the craze: “For the first time in our history, sales of rice are down. More people are eating bread.” And while white bread is still preferred, crustier baguettes have also become common. “The French are here now,” says Sakamoto. “Maison Kayser, Pierre Herme, l’Atelier du Robuchon have boulangerie outposts.”

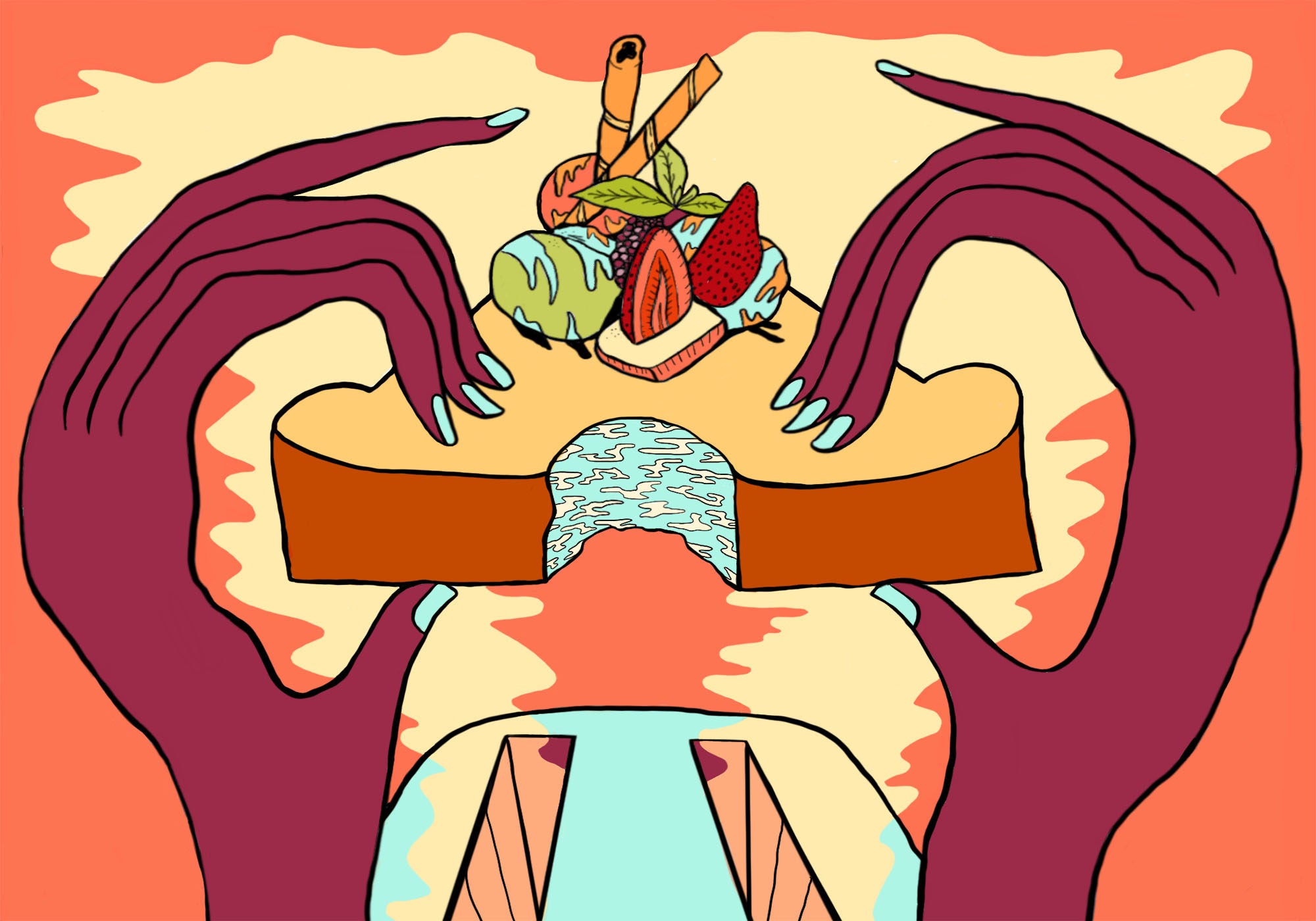

Sakamoto starts her day with a “morning set” at her favorite kisaten, or coffee shop. “One cup of coffee, it’s not bottomless; one really thick slice of toast called atsugiri with butter or margarine; and usually a hard boiled egg. For 400 yen [about $3.50], that’s cheaper than a cup of coffee at Starbucks.” Atsugiri is typically two to three inches thicker than a standard slice of Wonder bread. Even more extravagant: butter-fried Shibuya honey toast, a bread-bowl dessert popular with Japanese teenagers. “It’s almost half a loaf!” says Sakamoto. “The crusts are left on, and they toast it up, cut slices into it, drizzle with lots of honey, ice cream, cookies, sprinkles, whipped cream, and fruit.”

Purists, however, seek out bakeries known for the skill of their staff and their dedication to a particular strain of wheat from either Europe, America, or Japan. (The Imperial Hotel’s head baker, Hideyuki Kurokawa, has been rising at 3 a.m. for 22 years to produce the morning loaves—over 100 varieties.) “The Japanese appreciation for yakitate (hot out of the oven) bread is best observed at department store food halls—Ikebukuro Tobu, Shinjuku Isetan, Ginza Matsuya—where the baking schedule is posted so customers can line up for a fresh loaf,” says Sakamoto.

The line snaking out of Centre the Bakery in central Ginza attests to the appeal of hot bread. Over 2,000 loaves are sold here daily. The adjacent café specializes in toast. A shelf of deluxe toasters from high-end home appliance brands DeLonghi, Dualit, and Russell Hobbs line one wall of the dining room, where regulars choose their favorite machine and a waitress plugs it in at the table for a DIY toasting experience. (I choose the bulbous two-slot Rowlett Esprit, an old-fashioned model manufactured in Britain.)

Toast sets include three types of bread, each with a distinctive texture and flavor, as well as pats of butter from owner Takahiro Nishikawa’s dairy farm in Hokkaido. He also holds the Viron flour franchise for Japan and studied breadmaking in France. “I was born in a bakery in Kobe,” he says. “So I fully understand the essence of bread.”

I pull a slice of shokupan out of the toaster and take a bite.

It’s like eating a cloud.