For decades, Americans casually threw around the term “starving Armenian” to refer to anyone who was hungry. But to Armenian-Americans, the phrase is a confusing misnomer for a culture rich with cooking traditions.

At the turn of the 20th century, long before “Kardashian” entered the vernacular, Americans knew one thing about Armenians: They were very hungry.

Mothers in kitchens across America warned their children to clean their plates and remember “the starving Armenians”—and soon the phrase began to make appearances in newspapers and magazines.

As refrigerators came into popular use in the 1920s and ’30s, General Electric ran an inelegant ad touting the storage benefits and time-saving benefits of the appliance. “Work your menus up a week in advance, then proceed to make the items that will keep and store them in your electric refrigerator until it is time for them to appear in the limelight, for confiscation by your ‘hungry Armenians.’”

The term also appeared in an 1934 op-ed in a Pennsylvania paper about the changing diets of children. “At four o’clock, we tore home like starving Armenians,” the writer laments of her own childhood in comparison to the children of the 1930s. “Into the kitchen pantry we raced.”

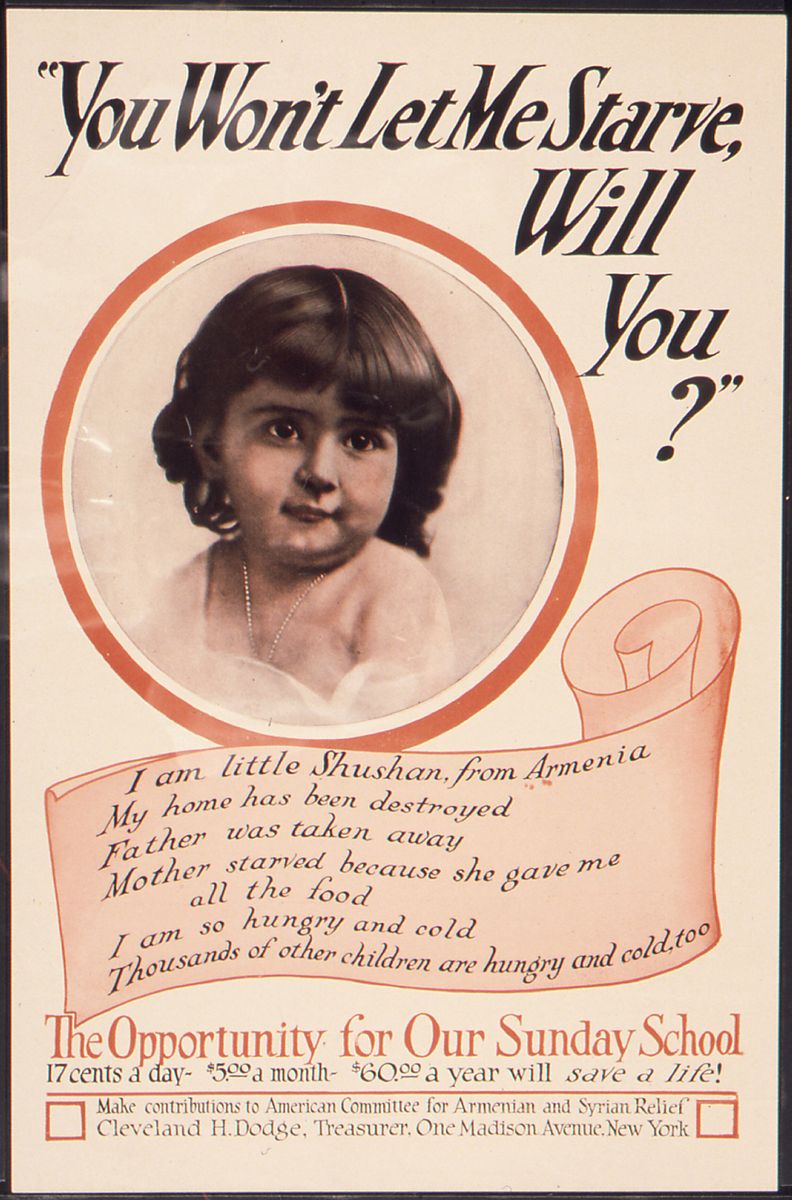

This bizarrely casual idiom began about 100 years before the current global refugee crisis, when America made its first collective display of international humanitarian aid, spearheaded by the American Committee for Armenian and Syrian Relief (now known as the Near East Foundation). Taglines like “Hunger Knows No Armistice” and “Lest We Perish” urged Americans to donate funds.

“You won’t let me starve, will you?” read a 1918 poster soliciting donations for refugee relief. It featured a cherubic young girl with dark hair and piercing brown eyes. “I am little Shushan, from Armenia. My home has been destroyed. Father was taken away. Mother has starved because she gave me all the food.”

The campaign, which has been all but forgotten today, was in response to the Armenian and Assyrian genocides of 1915, where over 1.5 million people were slaughtered in the Ottoman Empire and hundreds of thousands of children were left orphaned. Those who survived were exiled and dispersed across the world. The Near East Foundation’s fund-raising efforts saved the lives of a million refugees, sending food and other forms of aid to the “starving Armenians.”

This is how America largely came to know a population that had been indigenous to the area now known as eastern Turkey for thousands of years. When the campaign ended, the catchphrase stuck. It morphed from a call for international relief into a euphemism for hunger.

Even in the 1980s, it was a phrase that Christine Jerian Kharmandalian, a first-generation Armenian-American who comes from a family of genocide survivors, frequently heard growing up in the suburbs of Chicago. Her visits to a neighbor’s house always began with her friend’s dad turning to his wife and saying, “The starving Armenians are here! Make them a bologna sandwich.”

“I remember going home to ask my mom, ‘What does this mean?’” she says. For Kharmandalian, it was a confusing characterization. Far from buying processed slices of meat, and far from starving, her mother, both a home cook and a caterer, was preparing time-consuming delicacies from scratch, like basterma, a heavily spiced and air-cured beef Armenians were famed for in the “old country.”

What Americans didn’t know was that despite the moniker, Armenian families like Kharmandalian’s had a rich food tradition that had been cultivated for eons.

“We made everything at home,” she says. “My mom was selling homemade basterma for $15 a pound, and because Chicago was so cold, we could hang it outside, but we had to hang it high enough so the raccoons wouldn’t get to it because sometimes there would be bite marks in the beef.”

What Americans didn’t know was that despite the moniker, Armenian families like Kharmandalian’s had a rich food tradition that had been cultivated for eons and shared amongst various people of the area now known as the Middle East. And along with the thousands of survivors who came to the U.S. as some of the country’s first refugees, they brought these traditions and foodways with them.

In a new and unfamiliar country, they continued making cracked wheat and lamb meatballs called kufte with various spices, grew grape leaves in their gardens with which to make dolma, strained Armenian madzoon, or yogurt, in their homes, and rolled out fresh phyllo dough for dozens of syrup-laden pastries.

Having lost property, cultural heritage, and identity in addition to the millions who were killed, food became the most transportable cultural marker that could be made tangible with the right ingredients, as Armenians were forced to migrate across the world.

“There’s nothing that I can carry from anywhere to give me those memories,” recalls Kharmandalian. “All of those other things related to your family memories you have to leave behind, but the recipes and flavors you could take with you.”

These culinary traditions, however, did not stay contained within their homes. Instead, they spread across America, and like so many other traditions that immigrant communities have brought to the U.S., they changed the country’s landscape of food.

“Considering all the talk after the war about the ‘starving Armenians’ it seems sort of incongruous now to learn that the Armenians are considered among the no. 1 gourmets of New York’s foreign colonies,” wrote Mark Barron in the Montana Butte Standard in 1934. A 1939 column touted them as “gastronomic Armenians” and asked “whoever nicknamed them the starving Armenians?”

“Like any other persecuted minority that immigrated to this country, we brought with us our food and traditions—but as Armenians, regardless of wealth or social standing, food, along with our hospitality, is the introduction to our culture,” says Seta Dakessian, an Armenian-American chef and owner of Seta’s Cafe in Belmont, Massachusetts. “It was the safest way for people to accept us, and because of this, we were able to bring our rich traditions and culture to the U.S., slowly educating people and diminishing the thought ‘starving Armenians.’”

George Mardikian of Omar Khayyam’s restaurant, circa 1938 (photo courtesy of the San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library)

Through the likes of genocide survivor George Mardikian’s famous Omar Khayyam’s restaurant in San Francisco, who pioneered the introduction of Middle Eastern food like shish kebab to the public as early as the 1930s, American diners got a taste of “exotic” and “foreign” Near East delicacies, like seasoned lentil soup, baked eggplant, lavash, paklava, and rose-petal jam.

In California’s San Joaquin Valley, Armenians were essential in the cultivation of the agricultural industry, growing grapes, inventing new varieties of melon, and creating the foundations of the fig industry in America—a fruit that had been previously fed just to pigs. On the other side of the country, in Andover, Massachusetts, Armenian immigrants Rose and Sarkis Colombossian founded Colombo Yogurt in 1929. Based on traditional Armenian cooking methods, it was the first commercially produced yogurt in the U.S. It was one of several Armenian-inspired foods that were produced in the U.S.: The famous “San Francisco” treat, Rice-A-Roni, was based on an Armenian pilaf recipe given to the wife of one of the founders of the Golden Grain Macaroni Company by Armenian genocide survivor Pailadzo Captanian.

A book of recipes assembled by the Detroit Women’s Chapter of the Armenian General Benevolent Union in 1949

Soon, the recipes that had been orally passed down for generations were published in cookbooks, one of the most popular being Treasured Armenian Recipes, published in 1949 by the Detroit Women’s Chapter of the Armenian General Benevolent Union, a prominent Armenian nonprofit organization.

Because Detroit was a major landing place for survivors, it made sense for the most widely distributed cookbook to emerge out of the city, which attracted immigrants, refugees, and black migrants from the South thanks to abundant work in factories fueled by Henry Ford’s $5 workday. Settling largely on the city’s southwest side, Armenians opened grocery stores and coffee houses where they would serve the thick, pungent coffee drunk across the Middle East.

“Our preoccupation with food is probably directly connected to our past, when people starved to death,” says Yerchanig Joy Callan, a former Armenian-American restaurateur and culinary educator who was born and raised in Detroit. “You don’t consciously think about it, but you do carry your past. For us, as a small group, we care about our past a lot.” Though she’s been a member of the Women’s Guild of St. John’s Armenian Church in Southfield, Michigan, since 1999, for the last 5 years, Callan has been an essential organizer for the four month-long bake sales done by the guild in preparation for a much anticipated and popular annual festival held there.

Like Callan, Seta Dakessian, a descendent of genocide survivors who were adept in working with dough (her grandfather came from one of two families who owned a bakery in the Armenian quarter of Jerusalem), is attempting to preserve these culinary traditions. At Seta’s Cafe, she offers simple but hearty fare—the same foods she grew up with: stuffed grape leaves called yalanchi dolma, lentil and bulgur pilaf, and open-faced meat pies made with ground beef and spices called lahmejun.

A special item that makes a seasonal appearance is choreg, a sweet bread often made during Easter whose key ingredient is an aromatic spice called mahlab, the ground-up pit of sour cherries. More than any other food item, choreg is the most enduring icon of Armenian culinary cuisine—and by extension identity—in America. “It’s a common denominator,” says Dakessian. For many, the intoxicating smell of the mahlab brings recollections of parents and grandparents mixing. It survives as both a connection to past hunger and as a living, palpable sign that the future is full.