Once a fixture of the East End, surviving shops now serve the people squeezed out to suburban Essex and coastal hinterlands by rising rents.

London’s pie and mash shops are not for everyone. But they never were.

In 1851, London was a divided city. The air was thick with industrial pollution, and a prevailing west wind blanketed the East End in choking smog. Social classes followed the inky breeze: The rich and privileged moved west, into clean air; the poor were not so lucky. As the working class became established in the East End, so did the food they ate: pig trotters and pies stuffed with beef, mutton, kidney, and eel. The dishes were sold on the street, straight into eager hands: eels that had been writhing in the dank depths of the Thames that morning now steaming on its banks.

In the same year, social historian Henry Mayhew wrote that “men whose lives are an alternation of starvation and surfeit, love some easily-swallowed and comfortable food, better than the most approved substantiality of a dinner table.” In a Victorian society that valued respectability and cleanliness, street food was not “approved substantiality.” While the poorest of the poor had little choice, the aspirational working classes—plumbers, traders, and merchants living on the east side—looked to a newly established, firmly middle-class dining establishment, the restaurant, for inspiration. The workers wanted their comforting grub served within four walls, too. The eel and pie house, which today is called a pie and mash shop, was what they built.

The first opened in 1844, and as photographer and historian Stuart Freedman tells me, pie and mash shops were the first de facto working-class restaurants in London. “It was aping the bourgeois idea of a restaurant,” he says. Freedman has long documented the sociology of pie and mash shops, culminating with his book The Englishman & the Eel.

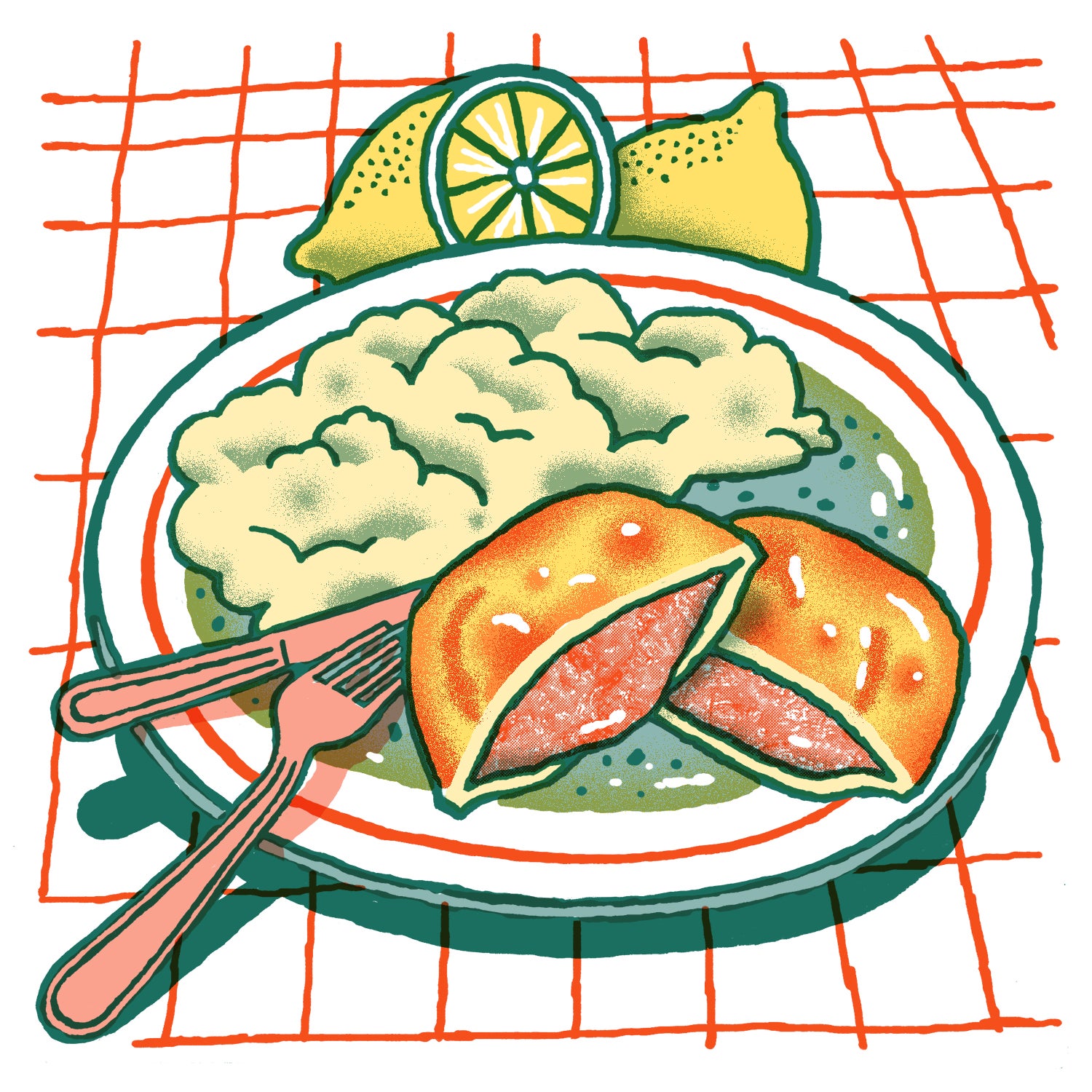

These places served hot, cheap, and sustaining food: eels stewed or jellied, mincemeat pies, plain boiled mashed potatoes and “liquor.” The latter is not what you’d think, with no alcohol in sight, but an oozy boil of eel juice and parsley, thickened with flour—a pallid green sauce with briny depth. As Freedman emphasizes, these early restaurants were sparkling establishments: White tiles winked, and sawdust was sprinkled on the floor to stop patrons slipping on spat-out eel bones.

Over time, three families took control of the pie, mash, and eel market: the Manzes, the Cookes, and the Kellys. Joe Cooke was allegedly the first to pair pie and mash with the liquor in 1862, and it remains the archetypal plate to this day. Each of the dynasties still has at least one shop in the city, but history has been unkind. In the 1940s, World War II bombings devastated the East End; 1980s housing policy and gentrification were equally ruinous. Surviving shops now serve the people squeezed out to suburban Essex and coastal hinterlands by rising rents; London proper has very few. Eel prices rise and stocks fall. Bones rarely hit the floor anymore.

Freedman is unequivocal when he states that you can’t reinterpret pie and mash for modern times. “It is what it is,” he says firmly. “It’s a very simple pie, a very simple mash.” His thoughts are echoed by Joe Cooke, owner of F Cooke in Hoxton, East London: “It hasn’t altered. It won’t alter.” Such lived history leaves rules and realities unwritten. Freedman compares ordering pie and mash to entering a betting shop. “If you’ve never placed a bet, it’s quite an intimidating thing to do: What are the rules?” The rules are as follows: It’s a “shop.” Never a “restaurant.” Mash has no butter. Gravy is forbidden. Ask for either, and in Cooke’s words, “You are gone.” Pie and mash is served with a fork and spoon. Request a knife and it’s not unlikely that you’ll be told to fuck off.

Becoming fluent in this unwritten vernacular requires a relative or friend to teach the ways. Rules are passed down within communities and families, learned as a child on the way to a football match or on the way back from the shops with Mum and Dad. Victorian sellers would even communicate in back slang to outwit customers; Cooke admits that this continues today. Vernacular builds a strong community with forbidding walls.

The significance of vernacular in food was explored in an American context by the Sporkful podcast in the four-part series “Who Is This Restaurant For?” Critic and writer Todd Kliman argued that “very often…restaurants are exclusionary spaces” and further explains his point of view in an article on Southern hospitality for The Oxford American: “Welcome is an almost mythic conceit, one bound up with the very ways the region chooses to think of itself…. But if we choose to see the South as it really is, and as it once was—and if we are honest in admitting that in many ways what is is not so very different from what was—then we find ourselves with a messier, more authentic picture.”

Request a knife and it’s not unlikely that you’ll be told to fuck off.

That messier picture is that of the pie and mash shop in London, 2018. Within the four walls, past and present barely differ; outside, the way London chooses to think of itself couldn’t be more removed from 1851. These are embattled, complicated, living political spaces, serving a largely elderly, working-class community. Many shops offer substantial discounts for over-65s; even at full price, one pie and one mash rarely tops £4 ($5.50). Freedman is quick to point out another crucial distinction: “Pie and mash shops are different beasts to cafés and restaurants—it’s fuel, it’s quick,” he says. Patrons are in and out within 20 minutes, taking time out from a shopping trip or making a pitstop on the way to a football game. These shops are not built for lingering. A one-star Google review for F Cooke says, “If you can afford food, then do not enter, if you can’t, then eat to your heart’s content.” In its ignorant snoot, the statement unwillingly gets to the meat of pie and mash.

So the shops are still serving hot, cheap, sustaining food, but as London’s restaurant culture has grown exponentially, pie and mash has been pushed to the margins. The aspiration that built them in the 1850s has been eroded over time in favor of the restaurant rhetoric that they made their own: Pie and mash shops are not restaurants, and so restaurant culture leaves them and their unwritten rules behind. If there’s a particularly biting irony, it’s the evolution of street food. Today, the street-food market is a palimpsest of the city’s dining scene, cherry-picking a shrunken globe of cuisines. In the 1850s, it was a fueling station. You can still pick up a pie at many London markets, but they will bear little relation to those found at F Cooke or M.Manze.

One aspect of contemporary food culture has taken nourishing root, and it’s the delivery market. M.Manze and F Cooke both offer mail-order pie, mash, and liquor; A. Cooke’s in West London, closed in 2015, lives on as a delivery business. Customers that have emigrated to Canada, Australia, and the United States email in with childhood memories. Facebook’s algorithm informs me that F Cooke customers talk about “parsley liquor and memory lane.”

But A. Cooke’s guest book tells another story. “Don’t take more of our landmarks away,” wrote a Gladys. This wistful tribalism inevitably has a negative underbelly, and the Internet spreads it wide: “Better than another curry shop” is a common abhorrence; pie and mash is one metonym for Brexit, us-versus-them, “we want our country back.” This is a sadder irony: Pie and mash, says Freedman, is “an empire of immigration.”

M.Manze is Michele Manze, who arrived from Italy in 1878 at three years old. His first shop opened in 1902. F Cooke was first opened in 1862 by Joe Cooke, who came from Wicklow, Ireland. This British institution’s history is more cosmopolitan than it first appears, but it remains fiercely contested. Any Londoner would love to tell you that the city’s food culture is inclusive, that it irons out creases between communities. At pie and mash shops, the creases push through cracks in pastry.

Pie and mash’s slow marginalization can also be put down to a tyrannical, paralyzing illogic of authenticity and myth-making that says things must be this way. Pie and mash’s willful steadfastness is both its lifeblood and its death knell. Regulars cherish and protect the unchanging rules: In the wider world, they are pasteurized into mythic, “authentic,” historical conceit. Their myths — whether or not you have mash, how the liquor is made, whether eels are stewed or jellied — are self-perpetuating but also an invention of distance.

Turning a living space into a curious collection of esoteric items tells its story with an airbrush, the messy truth concealed. This is how the vast majority of food media conceives of pie and mash: a historical curio ripe for a trivia angle or a tourist video. While talking about pie and mash shops as the last culinary representation of Victorian London might not be strictly untrue, and the historical bent most certainly brings in tourist business, it’s a double-edged sword. Such an attitude minimizes how vital the shops are for their patrons today, erasing the people who will stop in to see friends or neighbors, the regulars, the locals. The world at large perceives the shops as heritage items, not the community spaces that they are. It paints a past more important than the future.

It’s a past that weighs heavily to this day. It says a lot that the blue plaque — an accolade awarded to buildings of historical significance — is the pie and mash shop’s highest officially bestowed honor. It says even more that the shops are proud to display these plaques. That they keep them alive, in spite of muting that particular vernacular, etched invisibly in the tiling, scattered in the sawdust on the floor, and bubbling beneath the flaky pastry lid. The vernacular that speaks of contested identity, of class history, and of eels writhing in a pot.