In the ’80s, Skye McAlpine’s family fled the United Kingdom for Venice under death threats from the IRA, but she never knew she would still be there decades later, writing about her love of the city’s unsung home cooking.

When a bomb was found under the window of Skye McAlpine’s childhood bedroom, her parents decided it was time to leave England. McAlpine’s father, the late Lord Alistair McAlpine, was a renowned bon vivant who loved entertaining and who once gave his daughter two zebras when she asked for a hamster, but he also happened to be Margaret Thatcher’s treasurer and the deputy chairman of the Conservative Party, and as a result, he and his family were high on the hit list of the Irish Republican Army, which attempted assassinations of many top-tier members of the British government throughout the ’70s, ’80s, and ’90s.

Lord McAlpine and Romilly, Skye’s mother, moved the family to a pink palazzo they’d purchased on backwaters of Venice. The idea was it would be temporary: Skye remembers thinking, at the age of six, “Oh, gosh, fantastic, we’re going on holiday for a year.” She came to her new home with only two Italian words: gelato and ciao.

Now 34, she says, “We never left.” McAlpine, the author of the blog From My Dining Table and the new book A Table in Venice, splits her time between that same palazzo in Venice and a cozy flat in London. She strolls along the canals of Venice on summer evenings, a gelato in hand, with her five-year-old son, Aeneas, and her husband, Anthony, whom she met while studying ancient literature at Oxford and who works in finance. She makes weekly visits to Venice’s famous Rialto Market for the region’s best artichoke hearts, white asparagus, Tardivo radicchio, and, for the brief time they’re in season, zucchini flowers.

“I feel lucky because [my parents] taught me to appreciate and enjoy beautiful things,” she recalls. “They’d pause and say, ‘Gosh, doesn’t that ball of lavender look beautiful?’” Their comfort and honest pleasure in entertaining impressed her from an early age: “We never obsessed over perfectly cooked anything. For us it was always very much about who did we have lunch with, who did we have dinner with. And we always had an open-door policy at home. That’s become a huge part of how I live my life, and it has brought me so much joy.”

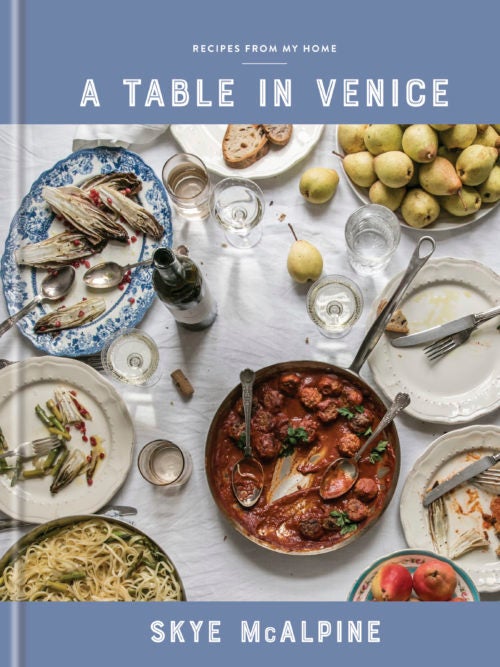

The stated goal of her book is to introduce a broader audience to “the unsung hero” that is Venetian food, and McAlpine does this with both classic and modified dishes that come from the northeast corner of the boot. There are options for breakfast (chocolate and orange ricotta cake) and lunch (chicken broth with tortellini) along with seasonal vegetables from the market (gratin of fennel), Venetian aperitivo (zucchini pizzette), and dinner (salt-baked sea bass), along with desserts (strawberry and vodka sorbet). But the overall effect is more than simply recipes: You want to cook and eat these things, but more than that, you want to embody a lifestyle in which you would—a lifestyle in which those delicate plates you inherited from your grandmother cradle homemade pastries, your friends and family gather each evening to sample what you’ve made as the sun goes down over the Venetian canals that make up your backyard, or you sip from a “spritz” as your vegetables, in season at this very moment, simmer on the stove.

Most Americans don’t live this way, and when reading McAlpine’s cookbook, I find myself wondering why. Why do I rush through meals, focused on sustaining myself and not the enjoyment inherent in the act of sustenance? Why does my concept of “healthy eating” tend to mean a kind of deprivation, choking down tasteless things that are “good for me”? Why don’t we all stop for lunch instead of eating it at our desks between emails? McAlpine touts the beauty of a bowl of lemons on a table, that “secularity of celebrating the everyday,” as the essence of Italian cooking, and it’s the promise of making life a little bit more beautiful, and so simply—just putting the lemons in the bowl—that draws me in, the same way it must with McAlpine’s 140,000-some Instagram followers and the many fans of her blog, which she started four years ago. What she’s offering isn’t just instructions for what to cook, it’s how to have a more sustaining, vibrant, delicious existence. Just look at her photographs and you’re halfway there.

When McAlpine started her blog, her son, Aeneas, was just one year old. Before he was born, she’d been pursuing her PhD—“specifically, Latin love poetry”—and took a year off for maternity leave, which led to an important realization: She just wasn’t passionate enough about her studies to make it her life. A friend suggested she write about something she knew really well, and her mind turned to food. “From there, I grew in confidence and started developing more of an interest in researching the recipes or the histories behind them,” she says.

She views her outsider/insider status (as a Brit in Venice) as a gift; after all, a cookbook author is a translator of food and habits and methods and culture, and being not quite English and not quite Italian gives her the liberty and perspective to interpret and convey the best of both worlds. When she began to map out A Table in Venice, she turned to old Venetian cookbooks written entirely in dialect, translating the recipes and adapting them to honor what she sees as the essence of her adopted home—while also making the dishes practical enough to cook if you don’t have access to Rialto Market.

This is something of a divergence from the traditional Italian opinion on the subject, but it works. “The Italians have a very strong view that there is a right and a wrong way of cooking something, and usually the right way is how their mother cooked it,” she tells me. “I felt like I couldn’t write the most authentic or authoritative recipe for artichoke hearts—I could only write what I really enjoyed. I did play around with the recipes, and when I found myself cooking something a couple of times for friends or family, I was like, ‘Okay, now it’s ready. Now we can put it in the book.’”

Along with the story of her life through food, McAlpine wanted to tell the story of “real-life Venice as I experience it.” The capital of northern Italy’s Veneto region, the city gets some 20 million tourists a year but has a population of just about 50,000 residents. “It’s so easy to come to Venice and think of it as a bit of a Disneyland, to wander around the center and maybe not eat terribly well and not have a particularly fantastic time,” she explains. “And to me what’s really exciting about the city isn’t just the amazing buildings and the cushy kind of canal views. It’s the improbability of it, that it’s an incredibly full, historic city built on top of water, which doesn’t make sense at all. Yet it lives and fully functions, and we live there and do normal things, like going to school or working a job.”

The slower pace in Venice restores her, giving her time to write, and ponder, and most importantly to cook. This is the story of her cookbook, too—that we should be gentle with ourselves, wherever we may reside, giving ourselves time to enjoy what’s beautiful in our midst: our friends, our families, our cooking, a fresh fruit. “It’s so easy for us to fall out of touch with this, either because we’re telling ourselves that we need to do something really complicated and showy, and then we end up doing nothing, or because we’re all incredibly busy.” She points out with the wisdom of a blogger that though digital life can provide a welcome sense of community, it can also take away from our time together. Which means it’s that much more important to take pleasure in what we’ve made and the world around us.

And when McAlpine writes of entertaining, of throwing together bigoli in salsa, a pasta with a creamy onion and anchovy sauce, or even just scrambled eggs on toast because she has nothing else in the house for supper, you not only believe that she really does live this way, effortlessly glamorous and well-fed in beautiful simplicity, but there’s also a certain pang as you wish you were there to share it with her. From that, you’re channeling not just her recipes, but her worldview. “Wouldn’t life be better if we all lived in a world or culture where we could pause and have lunch and enjoy that? I think it would,” she says.