A whole bunch of childhood comfort foods rely on some combination of starch and cream. For home cooks, they rely on the holy trinity of butter, flour, milk. Béchamel.

Comfort food, in its many forms, nearly always carries some memory of childhood. Backpacks and pencil cases. Construction paper and Elmer’s glue. My personal comfort food of choice, baked mac and cheese, is no exception—timeless, but also straight off the children’s menu.

Part of what makes mac and cheese such an important player in the comfort food codex is that it uses the long-standing template of starch plus cream. For my father, comfort food is a buttered baked potato. For my mother, it’s a bowl of cream soup and a slice of meatloaf and a hearty portion of bread.

“Cream soup will always make me feel better,” she said in phone conversation from her home in upstate New York. “But only meatloaf will make me feel more accepting.” A detail that caused me to wonder just how much bad news in her life had been delivered over meatloaf, and also to reexamine my own childhood. (Had we eaten more meatloaf the year Grandpa died?)

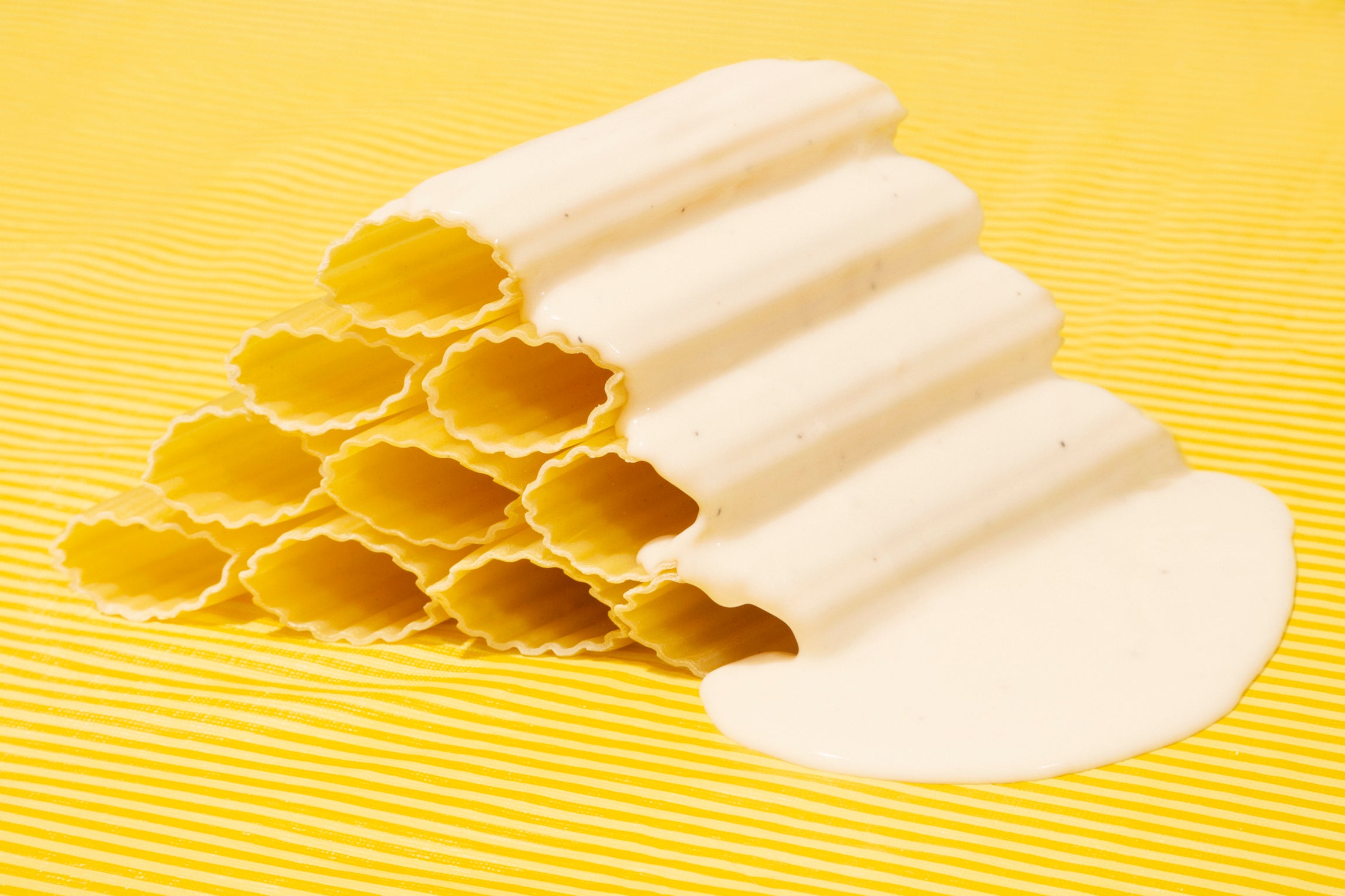

As a kid, this comfort formula was achieved through elbow mac and powdered cheese packets stirred on the stovetop. Now I get my fix with farfalle or penne, at least four cheeses, and a good béchamel sauce, liberally applied. Aside from the even more basic roux, béchamel is probably the fanciest-sounding sauce you make with what’s already in your pantry. There are all of three ingredients involved: butter, flour, milk. That’s it. The holy trinity of starch, cream, and comfort.

The sauce comes originally from Renaissance Tuscany, where it served as a basic thickener in soups and stews before Catherine De’Medici chefs brought it across the Alps. A century later, in 1651, Francois Pierre de la Varenne documented the recipe in his cookbook Le Cuisinier Francois, solidifying it as the “mother sauce” of French cuisine. (Among de la Varenne’s other achievements, he was the first to codify hollandaise, though it would be a further two centuries before any Benedict dribbled it over eggs.)

This hearty helping of historical backstory did not feature in the mac and cheese of my youth. (Back then, if pressed, I would have identified Béchamel as the capital of North Dakota.) But for me the comfort now comes as much from the preparation as it does from the actual eating: setting water to boil, grating cheese, browning flour and butter together, stirring milk, dumping a pot of frothy pasta through the strainer.

No one chooses their comfort food any more than they choose their parents. Though as with any loved one, they may have phases where they feel more or less in touch, swapping for more daring experiences, coming back when they feel vulnerable, reinterpreting the relationship. I hadn’t made mac and cheese in years when I thought to try again recently. The food may have come from my childhood, but the occasion for its revival was very adult (stood up for a date, then nearly clipped by a car while biking home in the rain.) I made it up as I went. Just put some pasta in boiling water, then drained it and added cheese. It wasn’t great, but it did the job. I was comforted.