Shakshuka is a simple enough recipe to make for your family. Except when it isn’t.

On the morning of our wedding day, my soon-to-be-husband and I sent for room service: coffee and Bloody Marys, a breakfast for the rest of our lives. Room service coffee is room service coffee, so there were no surprises there. But instead of already composed Bloody Marys, we were brought an ice bucket, two small bottles of Grey Goose vodka, a pitcher of tomato juice, a bottle of Worcestershire sauce, fresh horseradish, a bottle of Tabasco, salt, pepper, lemon wedges, pimiento-stuffed olives, and towering stalks of celery.

“You make it yourself,” I was told by the man who delivered it. And so I did, pouring first the vodka and then the juice into two glasses filled with ice, next spooning out heaps of horseradish, adding drop after drop—and then one drop more—of Worcestershire, and then tapping in some Tabasco, giving both drinks a swirl with a long-stemmed spoon, and sprinkling salt and pepper at the very end so that it rested on the surface. Finally, I liberally squeezed the provided lemon wedges, then ran the inside of the rind around the glasses’ edges.

“I think you’re going to be a good cook,” my soon-to-be-husband said, throwing back the freshly made Bloody Mary, opening his throat to the thick drink and draining it in one long swallow.

“I think so, too.”

I didn’t know, though. I didn’t know because I had never really cooked anything before. I was 19. In a sense, I had never really done much of anything before, yet I had always been doing a lot for my age. But that precocity had never extended to cooking, so I needed to learn.

Prior to making those Bloody Marys, I had never made any other food for my husband. We lived in New York City, and we were young and worked odd jobs and kept strange hours. We ate out and ordered in. Food was fuel, and it was one of the few things we didn’t romanticize in what was shaping up to be a very—overly—romantic existence: We were, after all, married within six months of meeting each other, and another six months after that, I would be pregnant with our first son. It was then, really, that making food myself took on a new level of importance—took on, actually, any level of importance.

But I didn’t really know where to start. Cooking is shaped by traditions and ritual, and I didn’t have much to fall back on. My own childhood had been filled with frozen French bread pepperoni pizzas, often microwaved instead of heated in the oven, so the bread bore the texture of wet cardboard, the meat chewy as a pencil eraser. There were boxes of instant mashed potatoes, whose soap-like flakes were not always fully incorporated into the emulsifying liquid; the clumps would sit in my mouth like wads of paper used for spitballs. And there was lots of fast food; by 11 years old I had the menus for McDonald’s and Burger King memorized.

This isn’t to say I didn’t know what a properly assembled meal looked like—I did. Growing up, I’d had those, too. The only difference was they were almost always prepared in service of something else—guests coming over, a holiday feast, a birthday celebration. There was ritual attached, but almost too much; I still didn’t know how to cook on a regular Thursday night.

My husband, though, had grown up with many routines. He’d been raised in Israel, just outside Tel Aviv; his mother had cooked every meal. The food was uncomplicated and inexpensive, reflective of the cuisine her mother, who had grown up in Libya before emigrating to Israel, had cooked. My husband would speak of these dishes—of hamim, a long-simmering stew of beans, potatoes, and beef on its bone; of the infinite varieties of salads, bright lemony bowls full of cucumbers and tomatoes, onions and eggplant; of the warm breads and bowls of hummus and baba ghanoush, all drizzled with tahini, garnished by the gaudy greenness of parsley and cilantro; of the shakshuka, with its sun-golden yolks bleeding into a hot, peppery stew—and I would listen.

Shakshuka is a simple enough thing to make. You start with a cold pan, pour in a glug of olive oil, and turn up the flame underneath. Then comes fat red bell peppers cut into curvy ribbons, paper-thin slices of garlic that melt into the oil, a sprinkle of kosher salt, and enough cumin so that your kitchen smells for a moment like sheets you haven’t washed in a couple of weeks. Once the peppers and garlic have gotten soft and the cumin mellows into something subtler—something that just hints of sex instead of slapping you in the face with it—add several handfuls of chopped, ripe tomatoes (canned work, too), and bring it all to a simmer. You’ll probably want to add more salt. After maybe 10 or 12 minutes, crack some eggs on the flat of the counter and slide them gently into the sauce. Once the whites harden but the yolks are still runny, turn off the fire and shower with cilantro. Then serve.

Shakshuka is a simple enough thing to make that there was a six-year period that I made it almost weekly for my husband and our two sons. It wasn’t a dish I’d grown up with, but it was one of the first dishes I learned how to cook when I got married. I wanted to cook food that my husband had grown up with in Israel and feed our children the food of his childhood. Without culinary traditions of my own, I set out to make his into ours.

So while there was no model for me when it came to cooking this food, no written recipes passed down to me from my mother-in-law, it didn’t matter. I paid attention to what my husband would say about the foods he grew up with; I paid attention to the dishes placed on tables when we’d go to his friends’ homes for Shabbat dinner. I hovered in the kitchen of the wife of my husband’s good friend, asking her what kind of fish she used in her Moroccan recipes and helping slice cucumbers and onions for salads and braid dough for challah. I could have, it’s true, sought advice online. I could have spent hours poring over Middle Eastern recipes and cookbooks, replicating dishes I found there. But I wanted there to be something organic in my cooking. I wanted it to feel like it was mine by shared experience, all the better to make it feel like it was ours.

And soon it did. I became well versed in a cooking tradition that I’d never dreamed I would call my own. I grew attuned to the different languages spoken with the hands, as they peel and dice vegetables, separate eggs, and prod the fleshy surface of fish, poaching in aromatic oil. I had never learned more than a few dozen words of Hebrew, but I felt like I’d mastered this other way of communicating, one in which I could also say “I love you,” one in which I could also show how much I cared.

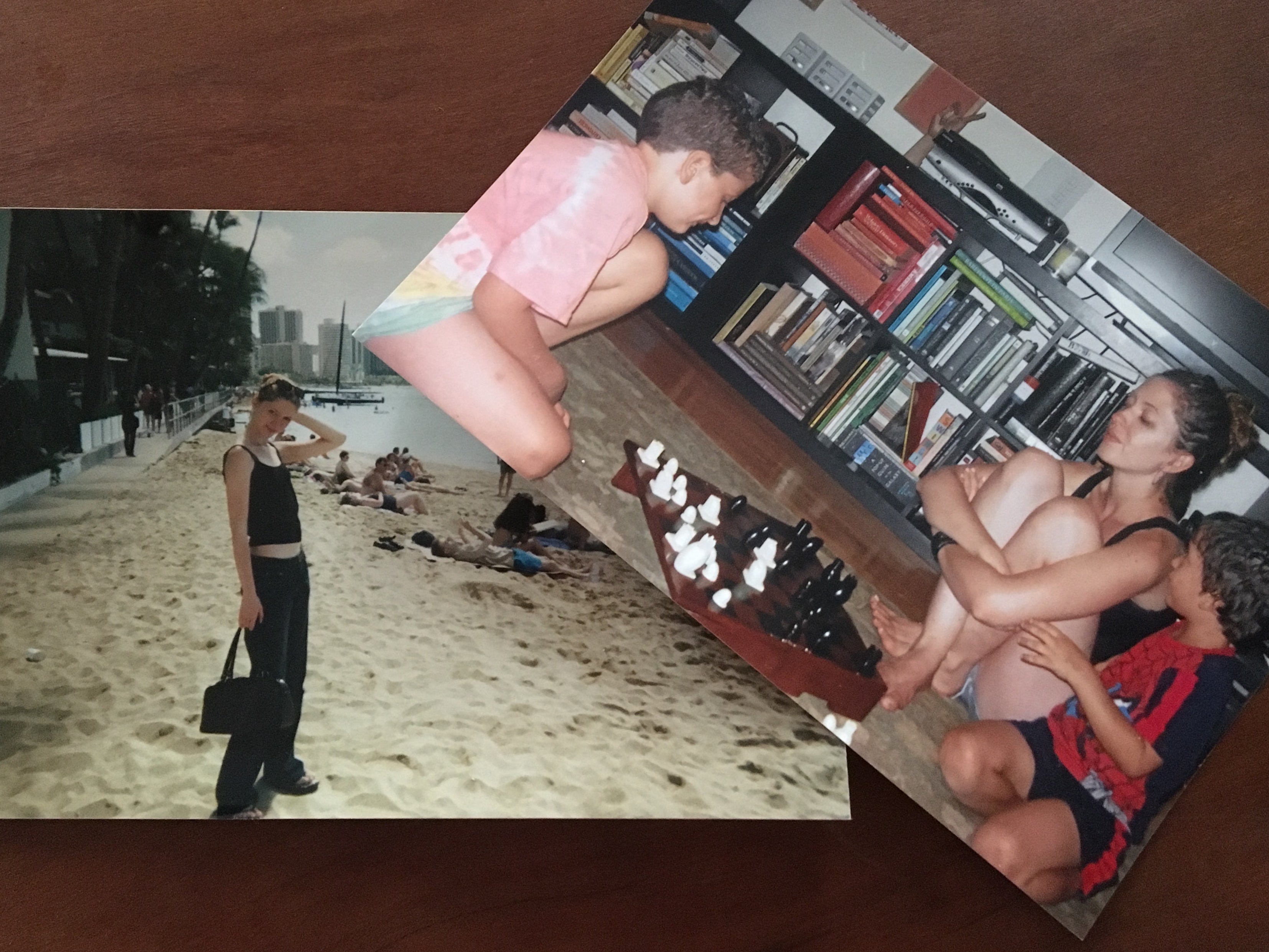

The author in Hawaii on honeymoon (left); the family playing chess.

One of the things people talk about when it comes to breakups is how difficult holidays become. Usually this is in reference to the severing of traditions, an inability to celebrate with the people who had become family, an acceptance of the fact that your children will not always be with you on these special occasions.

It wasn’t the holidays that were hard. This makes a sort of superficial sense—one good thing about marrying someone of a different religious and cultural background is that there is never any disagreement about where the kids will go on Rosh Hashanah or Christmas.

What was hard was the in-between. The routines that make up our everyday lives felt charged with a different energy. This was especially true with cooking. All the dishes that I had mastered over the years, they didn’t feel like mine anymore. They stopped making sense outside the context of my marriage. I felt like an imposter making these dishes I’d known for years. And so I turned toward other things.

I attempted to replicate dishes at restaurants I loved; I mimicked kale salads and pasta with sausage and sage. And I turned to cooking blogs, found recipes for meatballs and blueberry cakes. In bookstores, I would drift toward the cookbook section, amassing a small collection that I referenced not infrequently, until I didn’t need to flip to the appropriate pages anymore to see whether it was baking soda or baking powder that went into my sons’ favorite pancakes.

It’s been years since my divorce. My life has moved on and broadened beyond what I’d known was possible on that July day when I felt so proud of myself for making a Bloody Mary. I haven’t spent much time mourning the loss of my original cooking language. I’ve been too busy learning another.

And yet there came the day when I came upon Yotam Ottolenghi and Sami Tamimi’s popular cookbook Jerusalem leaning up against a stoop a few blocks away from my own. I picked it up and rifled through its pages, seeing variations of dishes that meant home to me, a home I thought I’d given up. I carried it with me to my new home and decided almost immediately what to make for dinner on that perfectly average Sunday.

Shakshuka is a simple enough thing to make. Or so the recipe read.

I served it to my children, and I served it to myself. We ate every last bite, swiping down the sides of the pan first with crusty bread, then with our fingers. It disappeared quickly, our simple feast, but I knew I would be making it again.