For some, a box of Bisquick is a magical path to baking bliss. For others, it represents a corner not worth cutting. And possibly something more sinister.

As a kid I shied away from frying pans and their menacing splashes of hot Wesson oil. But I did enjoy baking with my mother—hypnotically stirring batter and dusting a rolling pin with flour. I especially liked those mornings making biscuits, when I pressed my thick-lipped orange juice glass into a slab of dough to create perfect, powdery orbs I sent into the oven to rise and bronze. But this is not how biscuits looked or tasted in the South, I learned a decade later as a student at the University of South Carolina. This is because my mother’s recipe called for Bisquick.

She stopped working after I was born and whipped up wholesome, homemade meals daily. Yet my mother appreciated products that helped cut corners, and Bisquick—a premixed mélange of flour, shortening, salt, and baking powder packaged in a sunny yellow box emblazoned with blue lettering—was one such magical fix. The versatile mix birthed not only those (clunky) biscuits but too-stiff pizza crust, weekend pancakes my mother scented with almond extract, buttery crumb cake, and on lazy evenings when we didn’t succumb to Chef Boyardee, Sloppy Joe Bake: a mess of ground beef and onions seeping out from a canopy of golden crust.

A Betty Crocker tie-in from 1954

Bisquick elicited many dishes, sometimes zany, always hearty, that embodied a suburban Americana fueled by convenience. Across the country it empowered the panicked, lazy, and weary—who could not yet turn to a canon of televised cooking shows and instructional YouTube videos for assistance—to bake. Today the recipes integrating Bisquick, splashed on the box and found in pamphlets that were eagerly awaited in otherwise bill-stuffed mailboxes, seem decidedly archaic. But the role of Bisquick in the modern-day kitchen remains a helpful one, although it is admittedly less powerful than in decades of yore. Amid a culture that fetishizes farmers’ markets and pedigreed produce, some even deem it sinister.

“We used the shit out of Bisquick growing up,” Chris Shepherd, the chef and owner of Houston’s locavore-minded Underbelly, says. “My dad can’t cook, but the one thing he made was breakfast. My room was right above the kitchen, so on Saturday mornings I’d wake up smelling biscuits, pancakes, and waffles.” Bisquick chicken and dumplings were also a staple in the Shepherd household. “There are two forms of dumplings people grow up with,” Shepherd adds. “One is more rolled out and the other is where you drop spoonfuls of dough into the broth. I still make drop biscuit dumplings with Bisquick. I love it.”

Harlem, New York–based chef Therese Nelson, founder of the site Black Culinary History, was raised in Newark, New Jersey, by a single mother who “wasn’t that great a cook” and relied upon a stream of easy-to-find products, including Bisquick, to get her through kitchen duty. She’s not such a fan. Nelson recalls eating Bisquick pancakes that were always “rubbery and almost waxy,” reminiscent of fast food and frozen versions.

A print ad from 1967

“There are certain things that are always superior to a mix, and they tend to have simple ingredients, like biscuits or pancakes, so a product like Bisquick becomes the lowest form of the potentially sublime,” she says matter-of-factly. “The pursuit of deliciousness is afoot at every level of the food chain now, so home cooks can surely make a pancake from scratch.”

There is room for whatever folks want to stock in their kitchen cabinets, Nelson points out, and “while I don’t begrudge anyone their taco pies or whatever other semi-homemade shenanigans they are using Bisquick for, I guess I wonder why you would want to cook like Sandra Lee?”

Skittish, time-strapped home cooks like Nelson’s mother are exactly who Bisquick was designed for. According to parent company General Mills, the idea for Bisquick was first hatched in 1930 when one of its executives, Carl Smith, had a hankering for biscuits aboard a Southern Pacific Railroad train en route from Portland, Oregon, to San Francisco. Having ordered them long past the dinner hour, he was astonished when piping hot biscuits arrived shortly after. Perplexed by the swift delivery, he spoke with the chef, a visionary who revealed he had mixed lard, flour, baking powder, and salt ahead of time and stored it in the icebox.

Although it is mentioned in James Gray’s 1954 book Business Without Boundary: The Story of General Mills, it is not common knowledge that this forward-thinking chef, who is never named, or given inspirational credit, was black. Further, Los Angeles-based historian Linda Civitello reveals in her recently released book The Baking Powder Wars: The Cutthroat Food Fight that Revolutionized Cooking, that just as the pioneering chef on the train was written out of Bisquick’s history, blacks were left out of Betty Crocker’s 101 Delicious Bisquick Creations from 1933 and featured solely as servants in the 1935 How to Take a Trick a Day with Bisquick. At the time, grocery stores had yet to be graced with the likes of just-add-eggs-oil-and-water devil’s food cake mixes from Betty Crocker, another iconic brand owned by food behemoth General Mills, which also owns Bisquick, so Smith talked to the company’s chief chemist and boldly ventured into premade territory.

There were experiments and challenges—how to keep shortening fresh for months on end, for instance—and Bisquick was born a year later, a Depression-era salve for exhausted housewives offering promise in the slogan “Makes Anybody a Perfect Biscuit Maker.” Once its presence in other baked treats, including shortcakes and muffins, was deemed successful, that tagline evolved into “A World of Baking in a Box.” By the 1960s, a new-and-improved recipe featured more shortening and sugar.

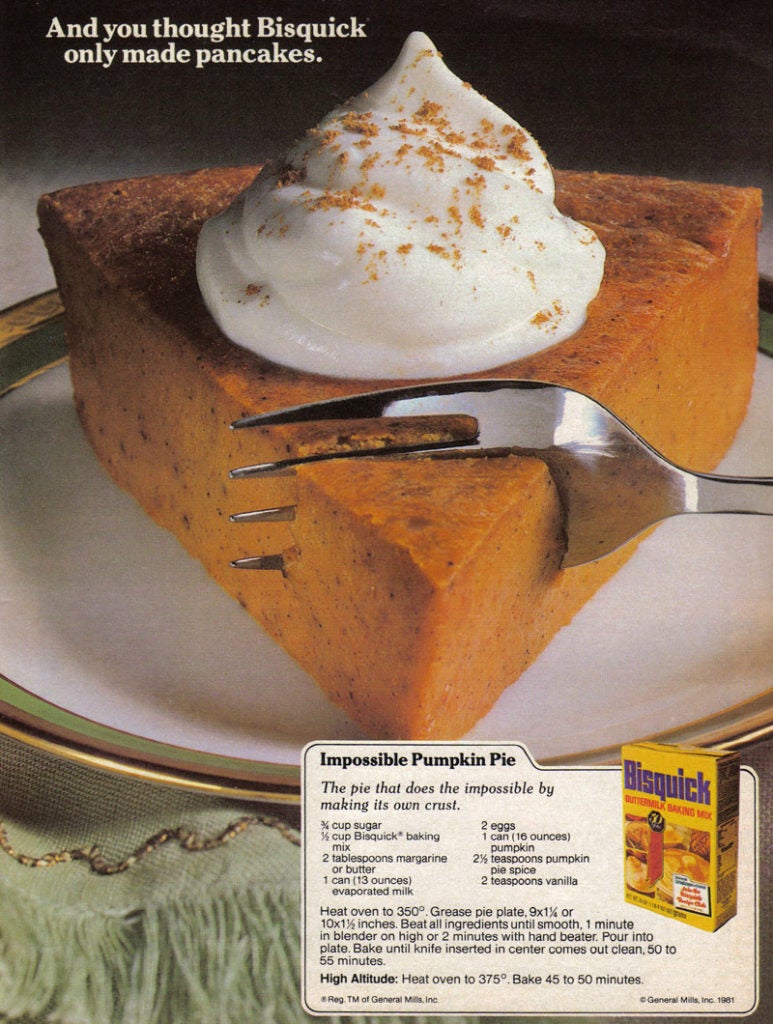

Burrito pot pie and zucchini-crusted buffalo chicken nuggets, among the myriad Bisquick meals found in the Betty Crocker recipe trove, might be messy, retro indulgences in a world besotted with, say, crackling boules of olive bread and from-the-farm plum tarts, but Martha Hall Foose, a Mississippi-based cookbook author, believes that “as long as there is homework, after-school activities, and seniors wanting some easy independence, there is a place for Bisquick.”

Perhaps out of nostalgia for the Impossible Cheeseburger Pie her babysitter used to prepare, Foose keeps Bisquick in her pantry “for a speedy cobbler.” There’s no shame in reaching for Bisquick, she says, when it gets families amped for baking: “If somebody makes anything and gets a feeling of accomplishment and has a positive experience, that keeps them moving in the right direction.”

A print ad from 1981

Nashville chef Rob Newton doesn’t use Bisquick, “but I’m not mad at it,” he says with a laugh. He remembers, during his Arkansas childhood, his mother turning to it for spontaneous batches of “quickie biscuits” and suspects that a number of people do likewise on the sly. Essentially, Bisquick has utilitarian appeal, he says, in that it reduces the number of ingredients you have to have around. “I think it is good when you consider it helps people still cook at home,” he says, agreeing with Foose. But the real downside to Bisquick, in his view, is that you have less control over the leavening and fat and flour ratios with the mix’s fixed amounts.

Raised in Fairfield, Connecticut, Anne Quatrano, the chef and owner of Star Provisions and Bacchanalia in Atlanta, says Bisquick always seemed to be in the cupboard. “My mother never cooked, but she would make a few items—waffles, chicken and dumplings—with the help of that mix,” she recalls. Today, Quatrano doesn’t see the point of Bisquick when there is an abundance of straightforward from-scratch recipes calling for minimal ingredients. “I believe it had a place 50 years ago, when it was novel,” she points out. “But when I ran to the supermarket yesterday I saw two shelves full of Bisquick, so I guess someone’s using it?” Like Shepherd, maybe they just can’t resist the allure of yesteryear’s drop biscuit dumplings.

Photo by Jake Cohen. This story has been updated with additional information regarding Bisquick’s history and recipe origins.