The rules are simple for the legendary Chicago chef: seasonal and delicious. The rest is just gravy.

Paul Kahan really didn’t want to write a cookbook. It’s been nearly 20 years since a literary agent first approached him, right after he’d opened his first restaurant, Blackbird, and Food & Wine had named him one of its Best New Chefs. Since then, he’s opened 10 more restaurants and become, if not an old chef, a mature one. His protégés have left the nest and opened places of their own—most recently David and Anna Posey, formerly of Blackbird, now of Elske, Bon Appétit’s number-two restaurant in America. Surely Kahan had a wealth of stories and experiences to share. But still, he resisted.

“I was not into a book that was all me, me, me,” he says.

But Cosmo Goss, the executive chef at the Publican, Kahan’s third restaurant, thought a cookbook would be cool.

“I annoyed him to death,” Goss recalls. “I said, ‘We don’t have to write about you and me. Let’s write about the people who make us look good.’”

It could be argued that Kahan makes himself look good. He’s known in Chicago and beyond for serving what he describes as elegant and imaginative Midwestern cuisine—farmers’ cheese tortelli, porchetta from pork raised in Fairbury, Illinois—with enormous flavors and impeccably sourced ingredients. When he opened Big Star in 2009, he applied the same care with flavors and ingredients to Mexican street food—inventive and delicious tacos like grilled steak with a Muenster cheese sauce and charred carrots slathered in mole—and thus became the first chef in Chicago to make “fine dining” accessible to anybody who could scrape up five bucks for a taco and a shot of bourbon. He regularly donates his time and money to charitable causes. He’s won two James Beard Awards. The Publican, which he originally envisioned, when he opened it in 2008, as a place where people could eat chicken and ribs and oysters and drink good beer—all things he happens to like—has spawned a bakery, a butcher shop, and a bar, as well as a location at O’Hare: It’s a small restaurant empire of its own.

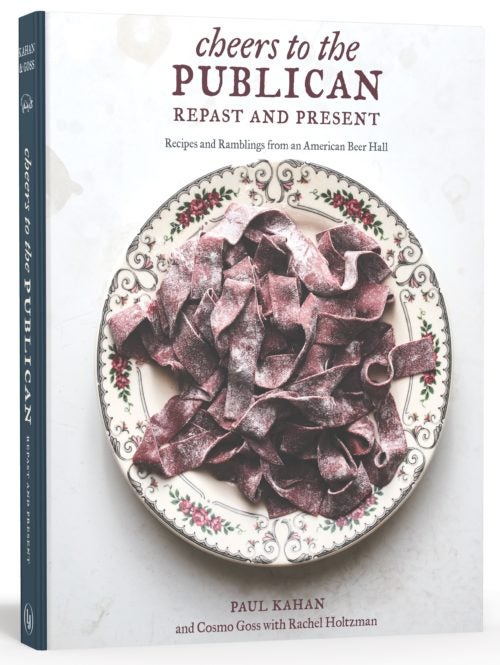

But Kahan liked the idea of paying tribute to the farmers, fishermen, suppliers, and cooks who produce and prepare the food that, as Goss puts it, makes the Publican look good. And now, two years later, Cheers to the Publican, Repast and Present, which he cowrote with Goss and Rachel Holtzman—a food writer who, he says, transformed his gibberish into something that sounded intelligent—is sitting in front of him on his kitchen counter at his home in the Albany Park neighborhood.

Paul Kahan and Cosmo Goss cooking in Kahan’s home kitchen in Chicago

It’s a warm Monday afternoon in October, and Kahan and Goss are drinking iced tea and getting ready to cook up a batch of pork country ribs with watermelon and sungold salad, with elotes on the side. The ribs are one of the mainstays of the Publican’s menu—Kahan got the original recipe from his friends Jason and Diana Monroe, who used to bring the ribs to Kahan’s annual Memorial Day barbecue blowout—and both chefs have cooked it so many times, they have no need to consult the cookbook. Technically, this is their day off, but they both spent the morning in meetings (Kahan had four, Goss had only two). As Kahan has gotten older, this has increasingly become his life.

“When you have one restaurant,” he says, “you’re in the kitchen every day. But now I’m almost 55, and I don’t have the time and energy I used to. My role has changed. Now I see myself as a mentor to young chefs like Cosmo.”

Goss, a 30-year-old California native, moved to Chicago seven years ago in order to work with Kahan. Next year, along with Erling Wu-Bower, another Publican alum, who is now working at the company’s Italian restaurant Nico Osteria, he’ll be opening his own restaurant, Pacific Standard Time, which he describes as “California hearth cuisine.” (This means they’ll be cooking everything in brick ovens.) One Off Hospitality Group will be a partner in Pacific Standard Time; nobody, says Kahan, could bear to break up the family.

“Family,” by the way, is a word that appears quite a bit in Cheers to the Publican—17 times, to be exact. Many of the photos in the book were shot and styled in this kitchen and in Kahan’s backyard, where there’s a raised-bed garden and a tool shed with excellent light that pleased the photographers, Taylor Peden and Jen Munkvold. The rest were taken during trips to the East and West coasts to visit various suppliers, most memorably to a spit of land on the beach outside Duxbury, Massachusetts, where the team cooked for Skip Bennett, their oyster supplier, outside in the rain. Like any family member, Goss is well acquainted with the inner workings of Kahan’s kitchen, including the six-burner Viking stove and the interior of the Sub-Zero refrigerator, which is so massive it probably qualifies as a piece of furniture. (Goss has an identical fridge in his own home.) When Kahan and his wife, Mary, renovated the kitchen a few years ago, they gave it a room of its own, a sun porch overlooking the backyard.

While Goss preps the salad and fields phone calls, Kahan goes outside to grill the ribs on the Weber kettle grill, trailed by his dog, Gabe, a fluffy white Samoyed. (Gabe makes a cameo appearance in Cheers to the Publican, staring longingly at a tray of ribs.) The secret, he says, is to dip them in the marinade every few minutes.

“It really caramelizes the ribs,” Kahan explains. “The book says to dip three times, but when I make it, I dip as many times as I can. You can’t overcook these, unless you leave them on for 45 minutes or something. The char is the best part.”

Kahan is a firm believer in char. He also likes salt and vinegar and fat. But mostly he believes flavor comes from using the best and freshest ingredients. “When I first started cooking [in the ’90s],” he says, “everyone was farm to table, but they just said it. I saw maybe two chefs at the farmers’ market.” In those days, Kahan, who’d grown up in his parents’ delicatessen and smokehouse in Chicago’s Rogers Park neighborhood, was in the middle of a 15-year stint at Erwin Drechsler’s restaurants, Metropolis and Erwin; he carried on the friendships he made in the farmers’ markets when he opened Blackbird.

Cooks on their way to the Publican kitchen. Photo: Peden + Munk

In recent years, though, Kahan noticed that it’s become much easier to get fresh meat and produce, even in the middle of winter, thanks to more farmers experimenting with hoop houses. He’s found a source for shrimp in, of all places, southern Indiana, thanks to Purdue University’s experiments with aquaculture. Even home cooks can order more difficult-to-find ingredients, like the espelette pepper that’s a Publican pantry staple, online. “It’s a good thing for Chicago,” he says. “Now there are a ton of independent restaurants.”

Kahan admires the energy of these younger chefs and restaurateurs. As for himself, he’s feeling a little tired. He misses his cabin in northern Wisconsin. “Youth is where ideas come from,” he muses. “Maybe you’re born with a bucket of creativity, and then you use it all up. You need new energy and new ideas to stay relevant and grow. People like Cosmo will be leading the way. I want to die in the Northwoods. Do you have to die in your restaurant to stay relevant?”