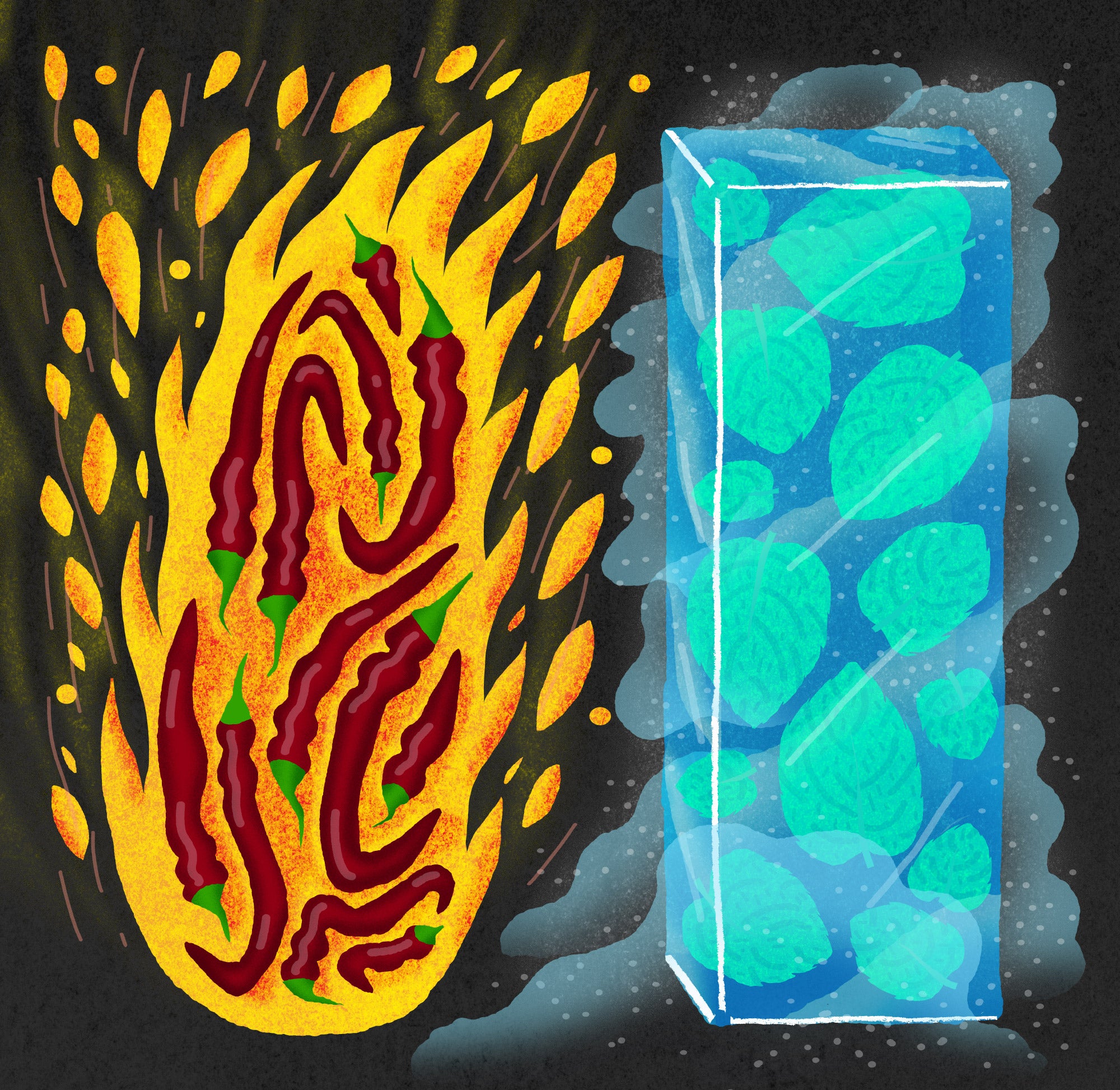

Why do some foods taste hot and some taste cold, even when they’re all the same temperature?

In dishes ranging from Calabrian pasta to Thai ground-pork salads, the heat of chiles is often offset by cooling herbs, like mint and cilantro. The combination of hot peppers and mint is found around the world, but why does it work so well? It turns out that chemicals in both of these plants have similar effects on the human body, even if they might seem to be opposites. So how do spicy and minty foods provoke a feeling of a change in temperature, even without a noticeably unusual temperature of their own? Spicy food burns, and mint chills, but of course neither food actually does either of those things in a physiological sense. It is a perfect example of how weird and stupid our brains are that room-temperature foods can somehow create a feeling of a changing temperature inside our mouths. They can even trigger physiological reactions: swelling, sweating, a runny nose. It is completely ridiculous.

The way our mouths and brains respond to certain foods—chiles, mint, eucalyptus extract, mustard, horseradish, alcohol—might seem mysterious. But your tongue has hundreds of nerve endings per square inch, and on those nerve endings are a variety of sensor proteins. “They respond to environmental stimuli and tell the nerve ending what to do,” explains Paul Wise, Ph.D., a scientist who studies chemical irritation at Philadelphia’s Monell Center, an entire institution dedicated to understanding taste and smell.

These proteins are basically locked gates, programmed to swing open and communicate certain sensations to the brain if presented with a certain key. Those keys can be anything: flavor, texture, shape, temperature. Some of those proteins are programmed to open up if they come in contact with capsaicin, the primary chemical in chili peppers that produces their spiciness. So if capsaicin bumps into that protein, the protein will unlock and let positive ions into the cell it’s guarding. When those positive ions are present in the cell, that triggers a series of reactions that sends an impulse to the brain telling it—and us—how to respond.

The first protein gate you have to meet is a member of the “transient receptor potential” family, usually abbreviated as “Trp” and pronounced “trip.” The specific protein within that family is called TrpV1, and it’s responsible for detecting and responding to changes in body temperature. For actual changes in temperature, it responds to heat sources above 42 degrees Celsius, about 107.6 degrees Fahrenheit. This protein isn’t responsible for letting your brain know when you’re snuggled in a nice warm blanket; there are other Trp proteins for that. Rather, it’s a panic protein, responsible for setting off alarm bells when you’re going to burn yourself. Its main method of alerting the brain is by sending out impulses to tell your brain to make the body feel pain. So when you eat a chile, the capsaicin in that chile bonks into the TrpV1 gate, unlocks it, and your body begins a process to alert the brain that something broiling hot is happening in the mouth.

Chiles aren’t the only compounds to trigger TrpV1; black peppercorns do as well, despite being wholly unrelated to chile peppers. Same with ethanol, which is why liquor burns when you drink it.

Another Trp, TrpM8, senses coolness. Unlike TrpV1, it’s not a panic protein, just one designed to let the brain know when some temperature change is happening—nothing crazy, no freezing temperatures, just a moderate coolness. That’s the protein that gets activated when you eat a Junior Mint. There’s also another bit of weirdness: Wise told me that at only three times the minimum concentration needed to trigger a feeling of coolness, menthol actually stimulates other receptors, like TrpA1. That’s the protein that mistakenly interprets foods like mustard, wasabi, and horseradish as “hot.” In other words, mint can be so cold it’s hot.

We don’t know exactly why our proteins work like this, or, maybe more accurately, why these plants work like this. Usually, plants want animals to eat their fruits; that way, we can poop out the seeds, allowing a new generation of plants to prosper. So why would the chile pepper evolve so that it actively irritates us?

Evolutionarily, it seems that chiles are doing their best to discourage us humans from eating them, which has had mixed results.

One theory is that chile peppers prefer birds to mammals when it comes to forecasting their seeds. Where omnivorous or herbivorous mammals chew, birds don’t; instead they swallow foods whole. When mammals, like humans, chew chiles, this weird TrpV1 issue irritates us and tricks us into a feeling of heat. Birds also, probably not coincidentally, are not sensitive to capsaicin the same way we are. So maybe the chile pepper is saying, “Hey, I don’t want you, boorish human or squirrel, to eat my fruits, because you’ll destroy the seeds.” It figured out a way to discourage some eaters and not others.

As for why mint has a cooling effect, one explanation is that, while humans don’t find mint’s coolness painful, other animals might; deer, for example, seem to steer clear of mint, which would protect the mint plant from having its delicate leaves devoured. The same strategy works for other herbs, like basil and sage.

Evolutionarily, it seems that chiles are doing their best to discourage us humans from eating them, which has had mixed results: We love eating them, so in that sense the capsaicin protection hasn’t worked all that well, but on the other hand, we love them so much that we’ve bred hundreds of different varieties and contributed to their biological success. There is something uniquely human about this; one theory holds that humans alone get thrills from skating close to the edge without actually being in danger, as with rollercoasters. Deer do not seem to have the same thrill-seeking behaviors, despite their penchant for jumping in front of cars.

But peppers can still be uncomfortably hot, so many cultures use herbs to cool things down. In Calabria, one of the only regions in Italy that uses chiles, torn mint is a frequent accompaniment to pasta tossed with olive oil, tomatoes, and cured chiles. Spicy noodle soups in Vietnam are often served with heaping spoonfuls of chile paste and piles of fresh herbs, like mint, basil, and cilantro. Spicy foods might not put us in any real danger, but if some part of our brains think they will, a sprinkling of herbs can quell the heat enough to keep eating.

Photo by Antonis Achilleos