In a new memoir, Alice Waters recalls the heady years leading up to the opening of Chez Panisse.

Chef and activist Alice Waters will forever be tied to her Berkeley prix fixe restaurant, Chez Panisse. Chez—the earliest champion of organic farming, inventor of the goat cheese salad, a sometime drug den and activist meeting hall—somehow still operates today, flawlessly, under the weight of its reputation. The alumni list alone, wow. Judy Rodgers, Deborah Madison, Jeremiah Tower, Suzanne Goin, Samin Nosrat, David Tanis, and Dan Barber, to name a few. In her new memoir, Coming to My Senses: The Making of a Counterculture Cook, Waters goes full rewind, beginning with lunches of rhubarb jam on Pepperidge Farm brown bread growing up in Chatham, New Jersey, and continuing on through dining with the Daley sons at Chicago’s Pump Room, a final migration west to Los Angeles, and later Berkeley in 1964—with significant time in France, too.

The final chapter, Opening Night, revolves around the day of Chez’s birth, August 28, 1971. “I opened a bottle of fumé blanc, and we toasted getting through the night,” the book closes on page 299. Point is, if you are expecting the stories of sex, drugs, and Jeremiah Tower served on a razor-blade-etched silver platter, this is not that book. Perhaps that will come later. Or perhaps those stories can be left buried out back in the tomato garden.

Press materials call the work “quietly revealing,” and there’s an undeniable whispery and measured tone that serves as a bit of a foil to David Kamp’s gossipy Chez chapters in his great 2006 book, The United States of Arugula. But this is not to say Waters’s writing lacks teeth. It’s hardly a bore. (A tense story about a prevented sexual assault has the author sharing painful life details with a mater-of-fact honesty.) I found myself devouring the later chapters quickest, where Waters’s evolution from party girl to prodigious networker and businesswoman was really starting to crystalize. I’m pulling for a part II. The Chez years, the continued activism, the school-lunch initiatives, locking horns with Bourdain. This ain’t thin soup.

It was tough picking a single section to excerpt, but I landed on this memory about France. How France had been an awakening for Waters, and how for a time that passion was bottled in the form of a cooking column in the San Francisco Express Times she wrote with illustrator David Goines. Introducing Alice Waters, journalist.

—Matt Rodbard

One afternoon in June of 1967, I walked out of David’s house and every house on the block was playing the Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band album. Every house. It was warm out, and you could stand in the street and listen to the music coming from the open windows. That was what the summer of 1967 was like in Berkeley.

Things were dark at that time in the country, but the Beatles brought back hope for us—their music was a message from England that was joyful and honest and deeply inclusive. Everybody related to that music. It was bigger than a person being elected into office—it was about love. And it brought me back. That was my Summer of Love. I was officially living with David by then, in the Victorian house with the turret. We had a big old table, and we always had lots of people over for dinners—food, like music, was always a grounding force, a way to return to what felt good and right and hopeful about the world, something that brought us all together around a table where we could talk politics or play cards. I was making crème caramel and chocolate mousse all of the time those days, because everybody liked those two things and spurred me on. There were other things I was making, too, but the homeruns were the chocolate mousse and the crème caramel. I would add Cognac or Grand Marnier in place of the vanilla extract in the recipes—that was my big culinary secret. I served that mousse one time and David said, “I hope you know this has more protein in it than the average Vietnamese peasant has in a week.” To David, everything was political; to me too, but I wasn’t about to give up the chocolate mousse.

When I started having all those dinners, I can’t say that there was any consciousness of my being a “cook” yet. I was interested in eating. When I got back from France I wanted to eat like the French, and the only way I could get those flavors again was by making the dishes myself. There were no restaurants in Berkeley and San Francisco cooking that way—or if there were, I couldn’t afford them. The process of cooking was demanding of me, it was—I had a certain taste in my mind, and I really wanted to get the food there. And I couldn’t do it at first. In the beginning I could never please myself except when I went to chocolate mousse or crème caramel, and people liked those no matter what.

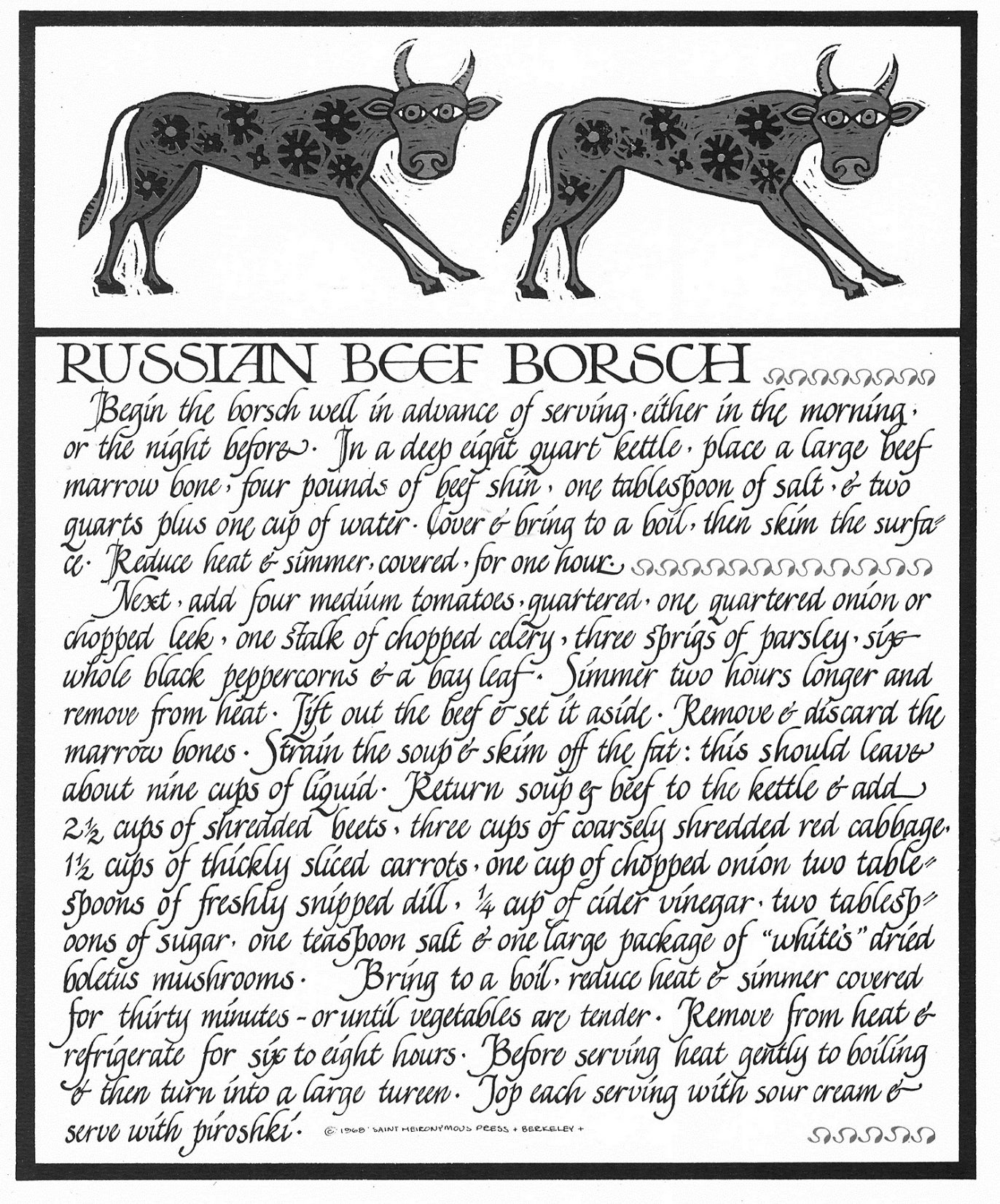

David and I came up with an idea to do a newspaper column for cooking for the San Francisco Express Times, a paper that was only around for about 9 months; I wanted all the people who worked on the Express Times to be turned onto real food. It all went back to France—I had been awakened to taste there, and I wanted everybody to be awakened the way I had been. I was so convinced I could win people over if I fed them the right food, if I got them to taste something that they’d never had before. That’s how the column “Alice’s Restaurant” was born. David agreed to calligraph it and do a block print for each recipe, and I would gather ideas for the recipes from my friends who cooked. I’d taste something a friend had made, write down the recipe, ask if I could use it for the column, make the recipe myself, see if people liked it, and then I’d include it. I don’t know that I fully gave credit where credit was due on those recipes—it’s hard with a recipe, though, because each one is so fluid, and if you change a couple things in it, it almost becomes your own. But it’s important, too, to recognize the people and the history and the traditions behind recipes, to know what they’re building upon. (That’s why I consider all the Chez Panisse cookbooks collaborations, with inspirations that come from a lot of different cooks. And I feel like once those recipes of ours are out there in the world, they belong to everybody—the more, the merrier.)

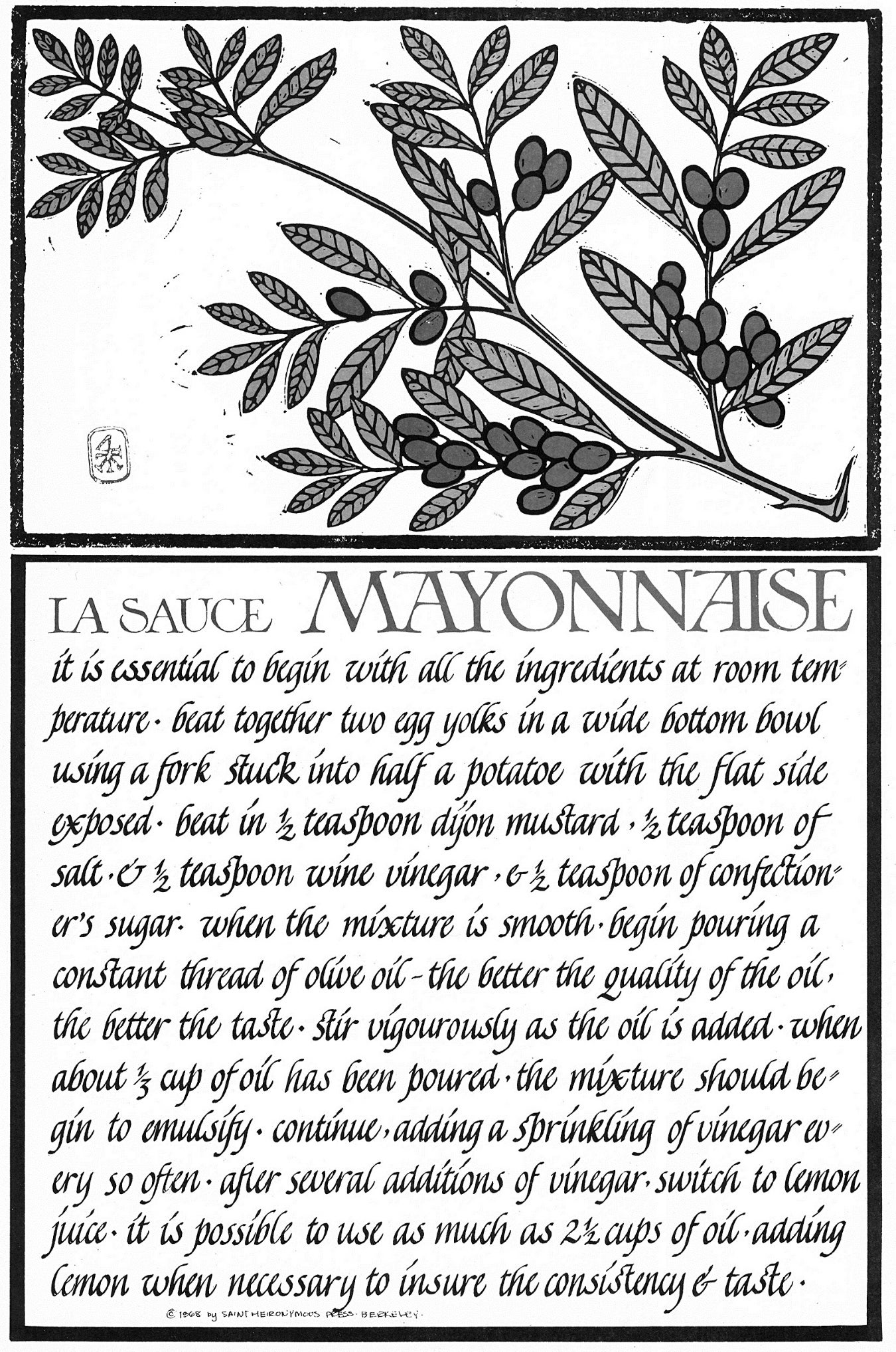

My taste had been awakened in France, but it wasn’t limited to just the French cuisine. We published recipes for everything from the most simple Moroccan carrot salad to a beef borscht from somebody’s Russian grandmother. I was obsessive about making every one of the dishes that went into that column, and obsessive about plenty of other dishes too. For boeuf bourgignon, I’d make a real beef stock with beef shank, or a salade crudité with carrots and leeks and a vinaigrette; or the very classic French dish eggs mayonnaise, which consisted of hard-cooked eggs with a loose handmade mayonnaise drizzled liberally on top. I had to make mayonnaise many times before I got it right, and I finally succeeded by sticking half a raw potato on the end of a fork and whisking the mayonnaise with that, once again, thanks to somebody’s grandmother, who had told me that that trick would make the emulsion work. Amazingly, it did. And so I wrote that exact instruction into my mayonnaise recipe for the column: Beat together two egg yolks in a wide bottom bowl using a fork stuck into a half potatoe [sic] with the flat side exposed. Because it worked for me. That’s truly how I made mayonnaise every time, at least until I got to Chez Panisse. Crazy.

A column called “Alice’s Restaurant” ran in the San Francisco Express Times, a paper that was only around for about 9 months, but left a lasting legacy.

Once I’d gotten the recipe right, David would calligraph it and illustrate it straight away, no editing, and then he’d send it in. I couldn’t control what he decided to draw at all—I just let him do whatever he wanted. For one recipe he chose to draw a castle and a medieval soldier on a horse and of course the dish, marinated tomatoes, had nothing at all to do with castles and knights! But when somebody’s such an incredible artist, as David is, there’s not much you can say. Plus, he was doing it all for free—for love. Most importantly, the illustrations were always beautiful, and people collected and adored them. A few years later, David compiled all of the Alice’s Restaurant columns into a portfolio called “Thirty Recipes Suitable For Framing,” which sold well enough to get him the money to actually buy his own printing studio.

David later did the same thing for the posters he made for Chez Panisse’s birthday every year—sometimes you couldn’t imagine what he had been thinking, because the image had seemingly nothing to do with Chez Panisse. And then, sometimes, it really did. Who knew what had been going on in his brilliant head, but the art that resulted was always unique and distinctive. His work became emblematic of Berkeley and you saw it all over.

After I came back from France, I realized that maybe I was tasting things differently than other people. There was a cookware store and bookshop in Berkeley called The Kitchen that I loved to visit; it was run by Gene Opton, a woman with strawberry blond hair and braids who wore these odd little peasant blouses and dirndl smocks, like something out of Heidi. It was Gene who gave me the English food writer Elizabeth David’s cookbook and it was a ray of sunshine. She was another Francophile who had been transformed after a visit to France; I identified with her walking through the French markets, discovering the flavors of steamed mussels, reveling in the mâche salad. It was so lucky that I learned to cook from her; she was able to write about food in this great freeform, elegant prose. Her recipes are in paragraph form, without specific measurements: “put in a handful of this,” or “add a pinch of salt.” Or she would say something like, “Get a beautiful butter lettuce, and dress it lightly”—that would be her whole recipe. Which meant you had to actually think about the cooking: Is this what she wants me to do? Maybe she wanted me to do it this other way? You were provoked to think about it and rely on your own senses more. I would have my own little conversations with Elizabeth David every day while reading her book.

Something can be lost in the writing down of a recipe. People can be so focused on measuring things that they’re not tasting as they go along, and at the end of it, they don’t feel the confidence to leave that form and cook without a recipe. That’s why I like great cookbook writers like Elizabeth David, Richard Olney, Diana Kennedy and Madhur Jaffrey, who can describe the raw materials in such a beautiful way, and then encourage you to go out to the farmers’ market and experience it all for yourself. That’s where the real learning happens. The famous French chef Alain Ducasse says that 85% of cooking is shopping; it may even be more than that, it might be 90%. But that’s not, of course, going to the supermarket—it’s going to the farmers’ market, or out in your backyard, finding what’s ripe and beautiful and alive and in season. This is my favorite recipe: go get some figs in August, put them on a plate, and eat them.

No, my favorite recipe is: go cut some mint from the garden, boil water, and pour it over the mint. Wait. And then drink. That’s my favorite recipe.

I spent hours and hours poring over my Larousse Gastronomique, which my parents gave me for Christmas 1966. The Larousse Gastronomique is an alphabetical reference tool, a formidable encyclopedia of French food, and I would lose myself in the maps of all the types of classic copper pots: sauté, frying pan, petit casserole, oval casserole for chicken en cocote, stew pan, large stock pot, pan for steaming potatoes, braising pan, two sided copper pan for making Pommes Anna. Every pan had a specific shape and a specific purpose, and I loved that I had all that information at my fingertips. Whenever people were over and asking me questions about food, I’d run to this book and look things up to pretend like I knew what I was talking about. I loved reading the descriptions of sauces, or examining the amazing little engravings, like an etching of a live woodcock, this tiny, delicious game bird—who would have known what it looked like? I was fascinated by the process of French cooking, but the book showed, too, that food was about more than just cooking—it was about geography, history, agriculture, tradition, art, anthropology, nature. It was something very sophisticated, and deep; It was about culture, and I had a huge curiosity about it. I still do.

After I came back from France, I realized that maybe I was tasting things differently than other people.

I started going to the new Williams-Sonoma store on Sutter Street in San Francisco. I was very interested in the kinds of rarefied cooking tools they had, things I had never seen before like melon ballers and lemon zesters. And they were the only things in the store I could afford to buy! Aesthetically, that store was fantastic. They had real French linens, and brown terrines with lids designed to look like the animal that was meant to be cooked inside: A green-headed mallard molded and painted for a duck terrine, a quail atop a quail terrine. And probably a little tiny one for a woodcock.

The supermarkets of the mid- to late ’60s were all about frozen foods and canned goods—the exact opposite of the French markets, and I figured out pretty swiftly that they were to be avoided, if at all possible. Instead, I went to the Berkeley co-ops where we bought things in bulk or I traveled to smaller specialty shops for particular foods. For charcuterie, Sara and I would go to Marcel et Henri in San Francisco, an old French place at Pacific and Polk Streets where we would get pâtés and saucissons. I also went a lot to the old Italian delicatessens in Oakland, like Genova Delicatessen, where we got olive oil, big long loaves of fresh Italian bread, olives that weren’t the tired green ones stuffed with pimientos, and hunks of Parmesan cheese that the deli workers would cut off of their big wheels. I got to know all those guys from Italy behind the counter, older men around 45 or 50 years old. When I approached the counter it always sort of felt like: “Here she comes!” I was so interested in what they had, and I was full of questions for them. They’d give me little samples to taste: “You like those olives? Try these too! Here, have these breadsticks!” It was a mutual flirtation, on both sides. It always smelled good in the deli, too—we’d pick up sandwiches before we left, the sorts where they’d layer in all the different cured Italian meats and a little pickled giardiniera.

Monterey Market was the best place in Berkeley for vegetables—but even so, there wasn’t a lot of variety. The produce I was buying at the time was limited to potatoes, carrots and parsley, or heads of romaine lettuce that I would pull apart, keeping and eating only the tender hearts. I could occasionally find small onions that would pass muster, and sometimes I’d buy Kentucky Wonder green beans, throw out the big ones, and pretend I had haricot verts. I was obsessed with the French haricot verts, the little skinny ones that they had in France. It was a texture thing for me—a green bean salad married so much better when you were using the little slender beans that took the dressing so well. It wasn’t until the mid-’70s when a French friend of mine went to the Chino ranch outside of San Diego and sent me back a big box of them that I finally had real haricots verts in the United States—I couldn’t believe it.

At the co-op on Shattuck Avenue, up the street from our house, we’d get things like rice or raisins or nuts, because the co-op was the least expensive place to get staples in bulk. You had to become a member—you’d buy a card for a nominal fee to get in, and that gave you access to shop there. My mother later bought me an investment plan through the co-op; health food believer that she was, she loved that co-op. The co-op was organic, it did have that going for it, but the produce always felt overgrown and wilted, no presentation like you’d find in a French shop, just piled haphazardly in a dusty bin. It didn’t excite me to cook with those vegetables: tired lettuce, limp carrots. And the store smelled a little bad—sort of like vitamin powder and bad incense.

Reprinted from Coming to My Senses. Copyright © 2017 by Alice Waters. Published by Clarkson Potter/Publishers, an imprint of Penguin Random House, LLC. Illustrations by David Goines.