Cookbook author and dogged journalist Melissa Clark is the voice of American home cooking. And she’s here to stir the pot.

Bones, bones, I need bones!” exclaims New York Times food columnist Melissa Clark, as she skips up to the meat stand at the farmers’ market near her home in Brooklyn. “Last week I got this big thing of lard from these guys,” she recalls, giddily. “Remember that thing of lard I got?!” she asks the two young men behind the counter, whose hands are shoved into pockets, shoulders hunched against the cruel late January cold. They smile and nod, then present Clark with a plastic bag cloudy with the smeared fat from assorted bits of bone and sinew.

“These are perfect!” Clark enthuses, after examining her haul. With it, she’s planning to make her weekly batch of bone broth. “I do pork and chicken all together, and it’s really good,” she says. “I know it’s like a thing now….” She rolls her eyes but is distracted from expressing further disdain by the sight of a precious delicacy at the seafood booth. “Oh, my God, are those bay scallops??!!” Clark shrieks, then sprints—in her puffer coat and ski hat she looks like a kid running toward a puppy—to get a closer look inside the marbled white plastic tubs. A woman already in line has just ordered what remains of the delicate mollusks. “Oh…are you getting all of those?” Clark blurts out, crestfallen. The woman takes one look at Clark’s face, laughs, and offers to let her buy half. “No, no, no, it’s fine! I just wanted to see if…” Clark turns to face the fisherman and ventures, “You don’t have any more, right?” Needless to say, Clark leaves with a small pouch of the scallops. “They’re just delicious in scrambled eggs, she says,” smiling broadly as she makes her way toward a table covered in good-looking leeks.

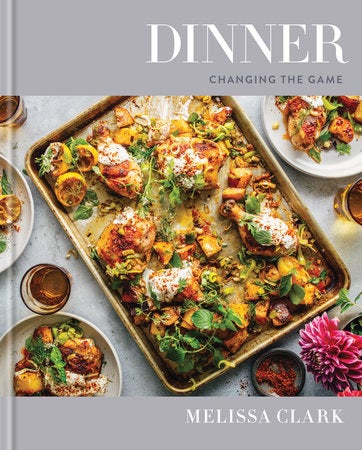

Clark has been writing about food since the mid-’90s, and these are her people—the men and women who sell her ingredients every week and the couple dozen rigorously bundled up Brooklynites she sometimes does good-natured battle with on Sundays in order to score the best black radishes and short-season sea delicacies. She’s the scribe behind an astonishing 38 cookbooks, some with the likes of Daniel Boulud and Bruce and Eric Bromberg. Her newest, a collection of single-dish, single-meal recipes, called simply Dinner, was released last month. And in it, you get a feel for the Clark of the irreverent yet expert weekly Times column A Good Appetite and the accompanying video series—both of which have turned her into a kind of niche celebrity. “I love your videos!” said a tall woman in yoga tights as she crossed the street in front of Clark earlier that morning. “Thank you!” Clark replied, with evident pleasure.

Clark’s onscreen persona is an appealing blend of casual and professional; she can afford the lack of pretention that makes her so pleasing to watch, caramelizing lemons or malting her fudge ripple ice cream, because she so thoroughly knows—and enjoys knowing—her stuff. “I always say that I’m the voice of the home cook,” she says. “I don’t want anybody to fail. That’s really important to me. Because you’ve gone out and spent all the money, and you are probably having people over, and you want it to be great! I don’t want them to be disappointed.”

Clark grew up in a household with two parents who loved food. “Julia Child disciples,” she says. “They were having gourmet dinner parties with their friends and making crazy tortes and galatines.” They were also both therapists, which in 1980s New York meant they didn’t work in August. This is how Clark found herself in Provence for the summers, falling in love with French sweets. “Sweetened condensed milk, eclairs, lemon tarts, and there was this chestnut pudding thing that you’d buy in the supermarkets called Marron Suisse,” Clark says, when I ask her about her earliest food memories. “That’s my madeleine.”

Food has always been Clark’s gateway to the world. “You can tell history through any lens, and food is mine; food is my metaphor,” she explains over dulce de leche lattes at her neighborhood café. “Even when I wasn’t writing about food, I was writing about food. My college thesis was on food in Don Quijote, you know? I mean, Sancho Panza eats a lot of onions. What does that mean?” This was at Barnard, where Clark studied English and history.

By this point in life Clark knew two things for sure: She wanted to write, and she wanted to eat. But it did take her a few years to figure out how to translate her uniquely multichanneled take on the world into coherent copy. First, she put herself through the MFA program at Columbia. “I worked full time at the university as a secretary at the institute for research on women and gender—that’s the only way to go because it’s so expensive,” she recalls. “But it solidified my identity as a writer, which is a pretty valuable thing because that’s a big part of the battle: Am I really a legitimate writer? What am I? Am I a fool?” Then she joined the ranks of the freelancer, “trying to write for Time Out New York, the usual” and worked in the front-of-house at restaurants.

Melissa Clark’s globe-spinning spice drawer

One of her early gigs involved bossing Mariah Carey around. “I was a hostess at this place on the Upper West Side, and Mariah Carey was my coat check girl,” Clark recalls. “As the hostess I was sort of in charge of the coat check girl. I mean, not really, but I had a little more status. So anyway, Mariah would sit there with her headphones on, singing, and I’d be like: ‘Mariah, can you get this man’s coat!!??’ ‘Mariah, can you get the phone?!?’” She takes a sip of her latte and laughs. “I barely knew her—I mean, it’s not like we were on great terms. She was not a good coat check girl.”

Clark got by as a dogged freelancer, and in 1998 she was offered the chance to apply for the holy grail for any young aspiring writer: a staff gig at The New York Times. “It was a full-time job as a news assistant, but it was one of those jobs that may or may not get you anywhere,” Clark muses about the hypothetical career path. “They could have put me on the science desk, and I wouldn’t have been writing, I would have been researching fossils. Actually, that would’ve been cool, so that’s not a good example, but—say they put me on the sports desk!? And now I am the assistant to the guy that writes about golf.” Clark turned down the opportunity, but started freelancing regularly for the paper. In 2007 she formally got her own column, but it wasn’t until 2012 that “they put a ring on it,” as she likes to say, and made her a full-time staffer. When I ask Clark where she got the gumption to decline a chance to apply for a Times staff job, she shrugs. “Well, because I wouldn’t be writing,” she says. “I wanted to be day-to-day writing, you know? It’s what I do.”

Five minutes with Clark will tell you she would not be well suited to a behind-the-scenes post; she thrives on interaction, which is unusual for a writer. “I take feedback really seriously,” she says. “I’m always trying to shape it and make the recipe better.” It’s why she loves the columnist beat: The medium puts her in a state of perma-dialogue with her readers and viewers, from whom she regularly solicits comments and suggestions. “What’s great is at the Times of course it’s now all online, and so I can constantly tweak,” she enthuses. Most writers would see this life of interminable editing as a kind of living hell, but not Clark. “Every time I make a recipe, I never make it again, because I’m always trying to improve upon it,” she says.

Clark, mid shakshuka

Clark is in life as she appears onscreen, lively and effusive, assertive but warm, like a cool elementary school teacher. But Clark also packs a born-and-bred New Yorker’s grit, determination, and persistence. At the green market she’d been chatting with her pickle guy, as she does every Sunday, when he asked if she had any “dynamite kimchi recipes.” He was considering adding it to his pickle repertoire. This was catnip for Clark. “I do! I do! I do!” she exclaimed. “I have a kimchi radish pickle! It’s soooo good! It’s just pickled kimchi radishes—a little anchovy, some chile flake, and then you let it ferment a couple of days on the counter. Are you going to start making kimchi? Please! Please!”

Clark offered to be “such a happy guinea pig” for any recipes he wanted to test out, then ordered kosher dills for her husband and a container of new pickles for her daughter. As she gathered her assorted shopping bags and began to make her way home, Clark turned and said: “So, I’ll see you with the kimchi next week!” The pickle guy laughed. “I don’t know if I’ll be that fast!” Clark smiled and gave him a long look—a homework assignment had been given—then repeated herself, more slowly this time. “So,” she said. “I will see you with the kimchi next week.”