The San Francisco chef wants you to pickle more vegetables, coddle many eggs, and embrace the beauty of barley flour.

On the very first page of Tartine All Day, right at the top of the third paragraph, Elisabeth Prueitt admits something that most cookbook authors don’t. “There’s no way around it,” Prueitt writes. “Cooking is work.” It’s a refreshing admission and a relief for anyone who has ever been led to believe that throwing together a meal for four on a Monday night is the stuff of effortless joy. “There are so many cookbooks out there that are like, ‘Cooking’s so easy, everybody should be doing it,’” Prueitt says. “If that was the case, there wouldn’t be any cookbooks.”

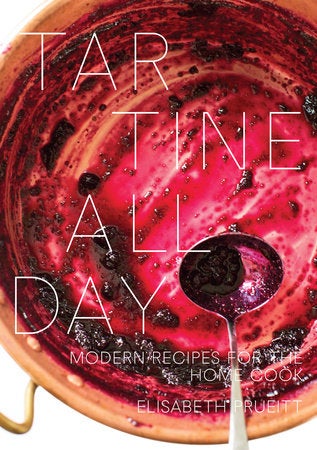

Prueitt has given San Francisco morning buns to wake the dead and croissants with greater mood-enhancing powers than Zoloft. But this, her second cookbook, is stocked with recipes that don’t adhere to her public identity as a pastry chef and seem destined to refashion her as a champion for the kind of thoroughly modern home cook who fears neither fermentation nor alternative grains. There’s cornbread in Tartine All Day, but it’s made with millet flour and masa harina, and a sauerkraut recipe that calls for a five-day fermentation. Pickled vegetables abound, as do baked goods made with teff, oat, rice, and barley flours. There is almost no wheat to be found in the book, but its absence stems not from the gluten-free zeitgeist but an epic irony: Prueitt, one of the country’s best pastry chefs, is gluten-intolerant. For some pastry chefs, this would necessitate a career change. But for Prueitt, it simply became an excuse to do what she does best. “I like finding new ways of doing things,” she says. “I’ll think of the classic thing, but how to change that thing.”

Since 2002, Prueitt has been best known as the co-owner, with her husband, the bread baker Chad Robertson, of Tartine, a tiny San Francisco bakery of outsize acclaim. Last fall, the couple opened Tartine Manufactory, a 5,000-square-foot bakery, restaurant, pastry shop, and ice cream counter that almost instantly became a sort of Lourdes for the food-obsessed. Many of its visitors were surprised to realize that Prueitt’s hand extended beyond the Manufactory’s pastry display case: She oversees the breakfast menu, which is stocked with savory dishes like coddled eggs with trout roe, and also advises on the Manufactory’s roster of soups, sandwiches, and salads in shades of green, yellow, purple, and orange.

Some of those salads appear in Tartine All Day, which, as its title suggests, caters to the home cook’s needs from morning until night, with a bumper crop of recipes that manage to be both imaginative and deeply practical at the same time. See, for example, Prueitt’s Vietnamese-style caramel pork ribs: Where most recipes call for sugar, hers calls for apple cider, which lends spicy depth to the dish’s sweetness. Prueitt began working on the book after Tartine’s planned (and highly publicized) merger with Blue Bottle Coffee fell through in late 2015; as a way to cope with her disappointment, she had started cooking at home “to change gears,” she says, and realized that the food she was making for her family, and developing for the Manufactory, could lend itself to a cookbook project. It was her first since the 2006 Tartine, which she cowrote with Robertson. “I’d been wanting to write another book,” she says. Tartine All Day gave her an excuse to expand her repertoire. “I get into ruts like everyone else,” she says, but developing recipes gave her what she calls “a burst of inspiration every day.”

Whereas Tartine is a joy ride through the pastry canon (croissants! brioche bread pudding! chiffon cake! rose geranium cream!), Tartine All Day is more of a thoughtful stroll alongside someone who understands the realities facing the average (albeit determined) home cook—or “the limitations of time,” Prueitt writes, that “can reduce the family meal to a slapdash event on most days.” The book is written from the perspective of a working mother, something Prueitt wasn’t when she wrote Tartine (Archer, her daughter with Robertson, is now nine); hers is a plainspoken but empathetic voice that echoes the messages found in other recent cookbooks written by successful women who are recalibrating the rules of dinner: Melissa Clark’s Dinner: Changing the Game, Food52’s A New Way to Dinner, Anya Fernald’s Home Cooked: Essential Recipes for a New Way to Cook, and Colu Henry’s Back Pocket Pasta all preach the gospel of inventive but pragmatic meals whose relative ease is blended with a message of empowerment.

Prueitt’s recipes aren’t easy in the meal-in-a-minute sense (the caramel pork ribs, for example, are baked for three hours, while a recipe for kuku sabzi, a Persian omelet, involves chopping a bushel of fresh herbs), but they do possess an earthy, technique-driven simplicity. Take Prueitt’s potato gratin: On first glance, it’s the same orgiastic union of starch and fat as any other potato gratin. But look closer and it contains the instruction to simmer the potatoes with milk and cream before baking the gratin in the oven; the step, Prueitt explains, catalyzes the cooking process and ensures even baking. The book is riddled with such useful, if not understated, tips, and little tweaks that transform a dish from the expected into the pleasantly idiosyncratic. A salmon salad gets a snap of brine from bread-and-butter pickles, while an eggplant Parmesan gratin forgoes breadcrumbs in favor of quinoa, and a riff on tabbouleh replaces bulgur with Job’s tears, a versatile grain native to Southeast Asia. In the dessert and breakfast sections, things get really interesting: Because none of the pastries use wheat, you’ll find banana bread made with almond and oat flours and carrot cake that owes its moist, springy crumb to teff flour.

That cake, not incidentally, is a fantastic rebuke to the notion that a gluten-free cake is a sad cake. It’s also a testament to the many hours of experimentation Prueitt has undertaken in service of better baking with alternative flours. “A lot of gluten-free recipes are simple white starches,” Prueitt says. “To me, that’s really frustrating. If you’re just taking out the wheat, you’re missing a lot of nutrition.” Tartine All Day’s lack of wheat, she adds, is “a reason the book made so much sense now.”

No one who has tasted Tartine’s pastries would guess they were created by someone who couldn’t actually eat them, but then, few of Tartine’s customers know anything about Prueitt. It’s Robertson who has always been in the spotlight, with his game-changing loaves of country bread and brooding-artisan-surfer persona. “It’s this interesting thing,” says cookbook author Samin Nosrat, who has been friends with Prueitt and Robertson for years. “He has this international reputation as this obsessed master, but Liz is absolutely no less obsessive. She’s a force of nature.”

Prueitt, who grew up in Park Slope, Brooklyn, and studied acting and photojournalism before enrolling at the Culinary Institute of America, was actually the face of Tartine back when it was just a farmers’ market stall. “My job was to do the selling and to bring our products to the stores,” she says. “Chad never wanted anything to do with that. But I always enjoyed it, interacting with guests and customers.” But in 2007, their daughter, Archer, was born prematurely, and the couple learned she had cerebral palsy. Prueitt stepped away from Tartine for the next several years to take care of Archer and in the process founded a nonprofit organization to fund a summer camp for kids with disabilities.

“It speaks to her obsessiveness and incredible vision that she could step away for so many years and [the bakery] would still hum along perfectly,” says Nosrat. “You got a sense of Liz’s presence almost by her absence. It’s that same thing with Alice [Waters], too: She’s not in Chez Panisse most days, but it’s absolutely Alice’s place.”

If you really want to bask in Prueitt’s culinary aura, you’d do well to visit her Instagram page. To scroll through her photos is to know spontaneous, mind-bending hunger: This is a landscape of matcha ice cream pies, warm whiskey-soaked prunes, brioche breakfast buns stuffed with soft-cooked eggs and bacon, and the aforementioned potato gratin, its crust a lacquered brown. When Prueitt was writing Tartine All Day, Instagram was a springboard for ideas; the site, she explains, “is sort of where I enjoy having an audience, and sometimes that would just inspire me to make and create. I like the performance aspect of it.”

She has no qualms about posting recipes to share with her 33,000 followers; instead, she finds it gratifying, an extension of her own appreciation “when creative people are open about what they’re doing and how they’re doing it,” Prueitt says. A recent recipe she posted for gluten-free chocolate almond cake, which is also in the book, earned 917 likes. On Instagram, it appears as a cluster of classic chocolate cupcakes, all topped with whipped cream. You wouldn’t necessarily guess those cupcakes have a secret to tell. But then, the same could be said for most of the recipes in Tartine All Day. “That’s kind of the comment I’ve been getting,” Prueitt says. “They’re recognizable, but there’s that Liz touch of something that’s different.”