Assessing the survival of “white treasure” produced on three continents

A security officer flagged my carry-on at the security check at Paris’s Charles de Gaulle Airport. I watched as a masked and gloved attendant unzipped my bulging burgundy plastic suitcase and unearthed its suspicious contents: six small twist-tied clear plastic bags the size of tangerines filled with glistening little snow-white crystals. My heart stood still as he held a package up close to his squinted eye for inspection. Would I be forced to give them up? These were not your average sea salts—this was fleur de sel, and it would cost at least twice as much as I had paid for a tiny canister of it once I touched down back home in the United States.

Thankfully, the agent placed the bags down and, without glancing in my direction, smushed my suitcase back together with the salts still in it. They were a prized souvenir from a brief sojourn in France, where I had visited the Atlantic coast of Brittany, home to centuries-old salt marshes—a patchwork of rectangular seawater pools that rim the shoreline like gray tiles when viewed from the air. Here coarse pebbles of gray sea salt, or sel gris, discolored by the mineral-rich clay earth of that area, are raked from the bottom of the marshes several times a day from late spring to early fall. And just once a day, unless it rains, a thin, crackly layer of pure, translucent salt forms on the surface of the pools like the top of crème brulée and is carefully scooped up to be sold for hundreds of times more euros per gram than sel gris. This is fleur de sel.

Fleur de sel may strike many readers as très French—a heritage artisanal product and fine-dining menu humblebrag like foie gras, truffles, and Échiré butter. It is, for the reasons described above, a worthy luxury: a rare confluence of ocean, wind, and sun that is gently harvested by human hands. Sprinkled on sashimi, crowning a chocolate truffle, or adhered to a butter-slicked slice of bread, fleur de sel’s thin, brittle layers give way with a gentle crunch. Because it’s so precious, fleur de sel is only used as a “finishing” salt, as these attributes would be lost if it was tossed into a pot of pasta water.

But fleur de sel is not just a French tradition. The phenomenon of creating “salt flowers” on the surface of seawater pools can happen in other parts the world, and it has been appreciated on windy coastlines far from France for centuries. But what is perhaps even more phenomenal than its formation is that it can still compete in today’s markets. In the months following my trip to Brittany, I spoke with producers, importers, and fans of fleur de sel—or flor de sal—in Mexico and Taiwan, where it carries a fascinating history all its own. And where, against all odds given industrialization, globalization, and the fact that you can make salt much more easily through vastly different methods in a lab, fleur de sel is still being commercially produced. This might cause us to wonder: Is fleur de sel worth its, well, salt? What role does this type of hand-harvested sea salt serve in a category crowded with canisters of kosher, Maldon, pink Himalayan, iodized, and flavored salts of every stripe? And why is its French-made variation so well-known internationally?

France

In Guérande, a small city with a walled medieval center in western France, there is a museum dedicated to the history of sea salt production in the area. Sea salt has been harvested from the dry, windy coasts there since Roman times, and the first written records of selling salt appear around the ninth century. The network of channels that sluice seawater into oeillets, or pools where salt is collected, was established by monks in the tenth century. Remarkably, this infrastructure and the tools for it—including a large wooden rake or las, which is wielded by a studious worker called a paludier—have changed little since then.

During the city’s boom times of the 14th and 15th centuries, sea salt was exported along the Loire river inland to Paris and beyond, and salt workers enjoyed special perks like bartering rights and the ability to buy cereal without taxes. But competition from Mediterranean salt producers started to heat up, and with the building of the railway in the 19th century came a significant drop in the number of Guérandaise salt workers, because it was easier than ever for cheaper imported salts to come in.

By the early 1970s, there were only about 200 of these craftsmen left, and a proposed highway project cutting into the salt marshes along the coast would have been the last nail in the coffin for Guérande’s salt industry. Instead, the local salt workers banded together to launch a successful grassroots protest of the highway—winning hearts and sympathies all over France in the process. From that point on, they determined that if they were going to have any chance at keeping their industry and their salt-farming heritage, they must become experts at not just making salt but marketing it. They must tell its story to the world.

Leading a tour aimed at telling that story this summer was Olivier de Villelongue, managing director of the trade group Salins, who showed our group of about 20 around the salt marshes after we visited Guérande’s museum. We carefully walked along narrow sunbaked mud paths separating rectangular saltwater pools that stretched into the horizon. A heap of sel gris lay at the edge of each pool, while bigger piles of salt collected from them sunbathed on a tarp to the side to dry. For every 15 or so large mountains of sel gris, there was a small bin of fluorescent-white fleur de sel. It was afternoon, and, as we squatted low to look at the surface of the oeillet that we were standing around, a frostlike crust of fleur de sel was forming around its corners. The ephemeral nature of this salt is such that its texture changes by the hour, we were told.

“If you don’t harvest fleur de sel quickly enough, the shape changes, and it becomes heavier and less expensive,” said de Villelongue. The role of a salt worker is to anticipate this moment, when fleur de sel harvesting is “ripe,” and to understand the rhythms of the marshes, intuit the weather, and maintain the pools with exacting precision. Paludiers often apprentice for years before harvesting salt on their own.

De Villelongue plucked a glistening shard from the surface of the pool and held it up to the sun. Each individual crystal of fleur de sel may look like a flower, hence its name “salt flower,” but it’s actually shaped like a hollow pyramid, he explained. This was no mere flaky sea salt but naturally formed, jagged-edged, pyramidal sea salt. By contrast, Maldon and other brands of “flaky” sea salt are made from seawater that’s been transferred to a lab, where they undergo proprietary processing. It’s often a trade secret as to how that’s done, and I’m told that there are myriad ways of doing it, resulting in crystals that don’t require a precise method of scooping from a pool or drying in the sun.

But does the difficulty of making a product make it somehow better? I wondered. Surely it would be all too easy to succumb to the romantic image of paludiers wearing mariner-striped sweaters gently assessing the water conditions for the perfect moment to reap white gold. Does any of this affect the taste or culinary usefulness of the salt in the end?

I placed a single fleur de sel crystal on my tongue and let it slowly dissolve. Moments later, a trickle of sharp ocean salinity creeping down my throat, as if teasing my tastebuds.

Mexico

Héctor Arias Solorzano didn’t know why the food tasted so bad whenever he traveled outside his hometown of Colima, Mexico. He spent a few years studying abroad in the United States and working for periods in Europe as a civil engineer before deciding to perform a taste test on tomato slices. He had a hunch. On one slice, he sprinkled some flor de sal that was harvested locally from the salt marshes of Cuyutlán Lagoon, about an hour’s drive west on the Central Pacific Coast, just as he’d grown up seasoning the food at his table every day. On the other slice, he sprinkled a small amount of “table salt,” or uniform granules of heavily refined and often iodized salt from a large canister like you’d find in any supermarket. The first tomato slice’s flavor intensified, almost as if it had bloomed beneath the crystals of flor de sal. On the second slice, “It just tasted salty, like a salty tomato,” recalled Solorzano in a recent phone call.

Because of its light and airy structure, flor de sal is less salty than a pinch of a heavier grain of sea salt, or closely packed fine salt. Studies have also found that the trace minerals present in unprocessed sea salts from around the world can impact taste—with iron imparting slightly metallic notes, magnesium and calcium a more astringent flavor, and more. These minerals also contribute to the nutritional value of the salt, and the exact mineral composition varies from region to region, resulting in unique tasting salt—saltoir?—wherever it’s harvested.

This striking revelation led Solorzano to better appreciate the pure sea salt produced in his region. Two years ago, he founded Marullo, an online retailer of sea salt and flor de sal from Cuyutlán Lagoon. Flor de sal is widely enjoyed and is not prohibitively expensive locally, he says (a one-pound bag of flor de sal from Marullo sells for about $259, about twice as much as the company’s regular sea salt). But it is a regional specialty, and not even all Mexicans even know about this “white treasure” from Colima, says Solorzano. That’s why he wants to share it with as many people as possible.

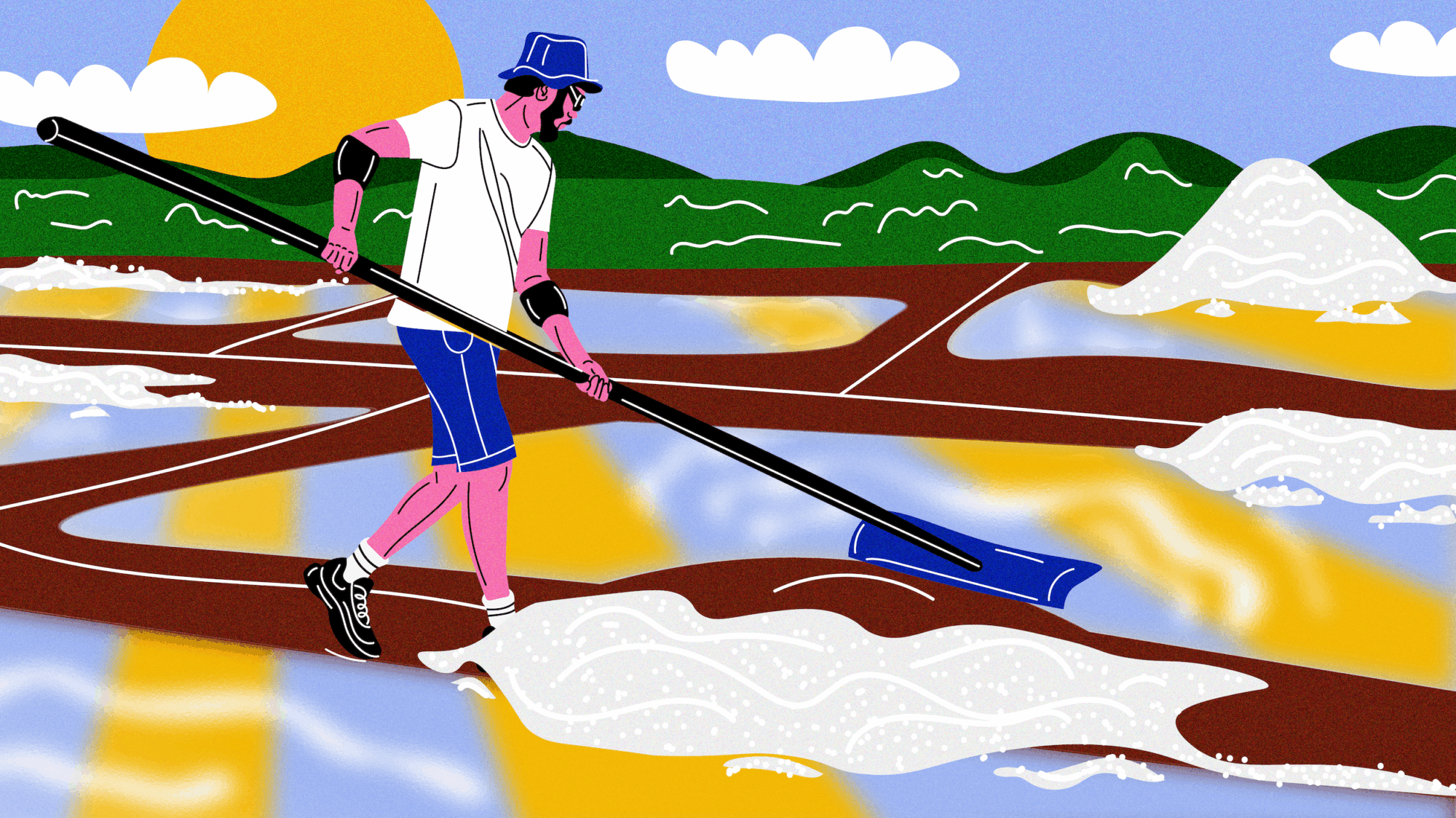

A salt field in Colima, Mexico. Photo courtesy of Marullo.

Sea salt has been harvested in the Cuyutlán Lagoon since pre-Columbian times. Many believe its production goes back two thousand years or more. Salt was, of course, critical to food preservation before refrigeration; there is evidence of its use in ancient religious ceremonies as well as an Aztec goddess, Huixtocihuatl, devoted to salt. Sea salt may have traveled from Cuyutlán to the ancient capital of Tenochtitlan long before the Spanish arrived in the region. The artisanal methods are similar to those practiced in Guérande, and salt workers, or salineros, often pass these skills down in their families for generations.

In 1925, these workers formed a cooperative, the Sociedad Cooperativa de Salineros de Colima, to preserve traditional methods of extracting salt. It’s a group of 300 that collectively sets the rules members must follow to ensure the quality of their product and maintain the environment. They’ve also ensured that outside corporations haven’t come in to take over and exploit the lagoon. This is how the integrity of Colima’s sea salt has been retained throughout the last century.

“It’s amazing that in this whole world that’s constantly changing, with AI and technology, we still use the same machinery in the lagoon, like small pumps and rakes by hand,” says Solorzano. “It’s a way to connect with our past.”

There are a couple other places in Mexico where hand-harvested sea salt including flor de sal is still produced—and one of them is the Yucatán Peninsula. Chef Maycoll Calderón first opened his restaurant, Cuna, in Merida, about 45 minutes from Celestún, on the Gulf of Mexicoo. There salt marshes are tinted pink from the presence of a flavorless algae called Dunaliella salina. Unrelated to the presence of pink algae, a huge flock of flamingos resides near these salt marshes, Calderón explained to me in a recent phone call.

The restaurateur behind Mexico City’s Huset and, as of October, Cuna in New York City says that he would prefer to use only flor de sal from Mexico in every dish if money were no object. But in his kitchens, kosher salt is used for cooking, while flor de sal is a compulsory finishing touch for dishes like ceviches, tostadas, and a roasted sea bass with ginger-infused rice and pickled mango.

“It has more minerality, and flavor-wise, I think it’s richer,” says Calderón of flor de sal.

And he believes that one of the biggest draws of using flor de sal is its health benefits.

“Processing takes the minerality and nutrition out of the salt, and many times they use chemicals that aren’t good for your body,” says Calderón. “When I visit someone’s house, I always tell them, ‘You should be using sea salt or flor de sal.’”

Taiwan

Another reason to appreciate traditionally harvested, unprocessed sea salt is that the methods of extracting it are entirely sustainable, using renewable energy from the wind and sun and human hands.

“You see that passive solar technology shared around the world with fleur de sel,” says Lisa Cheng Smith, cofounder of Yun Hai, a New York–based importer of Taiwanese pantry goods, over the phone.

Cheng Smith was struck by the legacy of these primitive technologies that still live on in Taiwan in an era fueled by resource-intensive hydrocarbons. A mountainous island surrounded by water, sea salt has been harvested on Taiwan for millennia, and there is evidence of its production on Kinmen island dating back to the tenth century. Salt marshes, or fields for evaporating sea salt including salt flowers, are believed to have been established along the southwest coast of Taiwan during the era of Koxinga, a Ming dynasty general who formed an independent state in Taiwan in the 1600s after expelling Dutch traders. (“Betcha ten bucks he didn’t call fleur de sel by the French name,” Cheng Smith wrote in a newsletter about Taiwan’s sea salt industry.)

Today in Taiwan, you can visit the vestiges of salt-producing regions, such as the Xiyuan Salt Field in Kinmen and the Qigu Salt Mountain outside of Tainan City, which have styled themselves as tourist attractions devoted to the history of a bygone time, as market pressures had forced most to close by the 21st century. However, in 2006, a group of citizens in Budai, in Chiayi County, decided to bring their abandoned salt fields back to life rather than just documenting their history. They received a federal grant, interviewed local retired salt workers, and spent six grueling years returning the Zhounan Salt Field back to its former glory. This salt is now used at local fine dining restaurants such as Taïrroir in Taipei and is sold in the United States through Yun Hai.

A worker skims fleur de sel at Zhou Nan salt fields in Chiayi, Taiwan. Photo courtesy of Budai Cultural Association.

What’s unique about Taiwan’s salt marshes is that the bottoms of the collecting pools—Taiwan’s oeillels—are lined with shards of broken pottery rather than bare clay or dirt, which radiate heat and help the salt evaporate faster. (Upcycling can’t hurt either.) In Taiwan, says Cheng Smith, salt flowers are typically skimmed from the surface of the pools once a day on spring and summer mornings, if conditions allow them to crystallize briefly before sinking to the bottom.

“You miss that window, and it’s not fleur de sel anymore,” says Cheng Smith.

In winter, when cooler temperatures require more time for salt to evaporate in the pools, the salt develops in a more “orderly fashion,” as she describes it, resulting in more uniformly shaped crystals—whereas summer salt flowers are formed more quickly and “chaotically,” resulting in more air in the crystals.

“You get this crispness and textural sensation without as much salinity.… It kind of helps bring out the sweetness in the salt in the same way as when you’re drinking wine with oxygen; it affects the flavor, you know?”

Cheng Smith loves to sprinkle fleur de sel into everyday meals like a bowl of fried rice with cabbage, or a dried daikon radish omelet for an unexpected pop of crunchiness and salinity.

Zhounan fleur de sel retails for $12.50 for a 40-gram canister at Yun Hai, the most expensive in a collection of sea salts from the producer. Yes, it’s still called “fleur de sel” in English because that’s the name by which most shoppers at the e-commerce site know this natural product best. The Chinese characters for “salt flower” appear next to the product on the webpage.

After they survived the security check and made it safely home in my carry-on, I distributed the sachets of fleur de sel to my friends and family, saving one for myself. Summer tomato season came and went, and at times it felt like an overabundance of riches to have peak in-season produce to pair with my newly acquired salt flowers—and my newly crystallized salt knowledge. A bed of cold noodles with ground pork and cucumber. A grilled eggplant slice. A wedge of cantaloupe. A bowl of steamed eggs. As I ate, it was hard to tell if I was tasting salt flowers or ruminating on their history. Their healthfulness. Their purity. Their improbability.

Not all coveted artisanal foods around the world have withstood the test of time. Perhaps the survival of salt flower production today speaks as much to our appetite for story as for a mineral-rich, lower-sodium, crackly-textured finishing salt. Among the online listings for fleur de sel or flor de sal, I didn’t see any without at least a paragraph of backstory in their product description.

With that information, that story, we can sprinkle fleur de sel on a tomato slice and feel a connection to the past. We can feel secure in knowing that the product we’re tasting is the same thing we’ve read about because it is so rare and because so few are still making it—unlike the way that tomato was probably grown, or the way a chicken was raised, or an egg.

Without a story, these pools of saltwater and its delicate bounty might have vanished long ago. Thankfully, a handful of producers are still telling it and selling it. And it continues to be written.