Chefs, influencers, and booming demand from the dining public are recasting an often-maligned flavor.

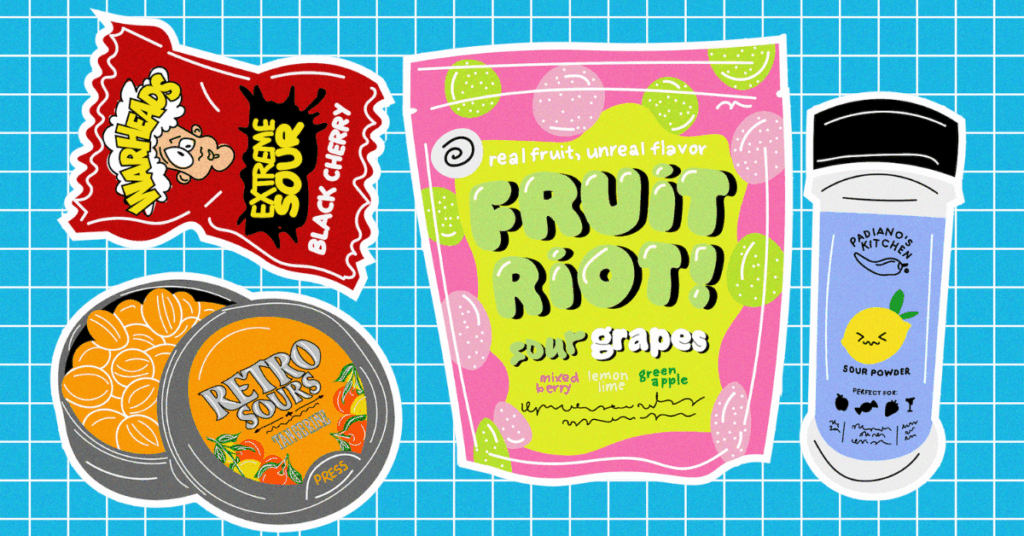

On February 4, 2024, the content creator Christina Kirkman posted a TikTok video of herself in the passenger seat of her car, eating frozen grapes coated in citric acid from a new snack brand called Fruit Riot!, which had launched a few months earlier in the United States. “Holy shit. They weren’t kidding, they’re really sour,” Kirkman says in the video that launched a thousand similar videos on the internet of people eating—nay, grimacing—their way through pouches of uber-sour frozen fruit. “Nature’s candy, now even candy-er” is one of the brand’s taglines.

From sour grapes to dill pickle–flavored chips and every puckering moment in between, people can’t seem to get enough of this very real, very bracing trend in food. And while a tendency toward tartness has been brewing for years, the recent impact of social media and its ability to both collapse and expand our horizons has supercharged an insatiable and at times extreme appetite for all things sour.

Sourness is the taste associated with acidity, which is measured using a pH scale. Anything with a pH below 7 is considered acidic. The lower the pH, the more intense the sourness. Sour Patch Kids are said to have a pH level around 2.5, close to that of vinegar, while peanut butter has a pH of roughly 6. If you’ve ever seen those timeless memes of a baby nibbling at a wedge of lemon (~2–3 pH), you’ve seen the visceral power of pH—the pucker, the recoil, the sense that there is pleasure but also pain. So why do we willingly subject ourselves to this?

There are some interesting hypotheses in the scientific world as to why humans eat sour foods, but there’s surprisingly little consensus. “It’s more complex than we think and probably one of the understudied tastes,” says Julien Delarue, an associate professor of sensory and consumer science at UC Davis. Sugar signals energy-rich carbohydrates, while bitterness once warned of poison. But as recently as 2022, a research paper titled “The Evolution of Sour Taste” underscored just how little we know about why sour foods exist in our diets. The paper’s authors concluded that acidity might indicate a lack of harmful bacteria, making food safe to eat. Or maybe it’s a signal of vitamin C, also known as ascorbic acid, an essential nutrient that our bodies can’t produce.

Regardless of the prehistoric why, the question of how we eat sour foods opens up a much more interesting discussion, at least from a gastronomic perspective. From unripe mangoes to sourdough bread to Thai fermented sausages, the world of sour is a wide, wild place, and it has been for as long as intrepid eaters have braved a little bite in their fruit or seen bubbling, festering foods as “delicacies rather than decomposition,” as the vinegar whisperer Sandor Katz writes in his seminal book The Art of Fermentation.

Sourness also triggers the unique but purposeful physiological response of salivation, which protects our teeth from the acidity of sour foods. In addition to maintaining good pH levels in our mouths and stomachs, saliva helps with digestion. Maybe this is why, in both traditional Chinese medicine and Ayurvedic practices, sour foods are necessary for a balanced diet. “Culturally, food is medicine,” says Vijay Kumar, the executive chef of the South Indian restaurant Semma in New York City. Kumar is from Tamil Nadu, where tamarind provides nearly all of the cuisine’s characteristic sourness, seen in dishes like the brothy tonic called rasam. “Growing up, we didn’t really go to doctors,” Kumar says. “When we had a cold, my grandmother used to make rasam with tamarind and black pepper,” he adds.

This halo of healthfulness is a meaningful connection to the past, but the growing mainstream popularity of these culturally specific sour foods might be rooted in something far more modern: the flavor-curious diner. “Gen Z is more likely than any other generation to want adventurous flavors, such as sour and bitter along with savory and spicy,” states a 2025 trend report from the Food Institute.

For these flavor seekers, restaurants and even the local grocery store have become a wonderland of possibilities, aided by the endless scroll of social media illuminating the global range of sour foods, from tamarind to pomegranate molasses to chamoy, a tangy pickled fruit condiment from Mexico. “When I discover a new sour ingredient, it feels both familiar and exciting,” says Yasmin Shahida, who posts videos of herself dining out under the account @traveleatnyc. “Restaurants, for me, are one of the most powerful ways of experiencing culture in its most sensory form.”

This infatuation with sourness is having a real impact on consumption: The Nation’s Restaurant News (NRN) reports that yuzu has seen a 29% increase on restaurant menus since 2020. In 2024, South Korean exports of kimchi reached a record high.

There’s a connection to be made between fermented foods like kimchi, probiotics, and the rise of wellness culture, but what’s more persuasive, to me at least, is that sour flavors are more essential than ever because they add vibrance to anything in their reach. “Sourness brings contrast, balance, variety, zing—pleasure,” writes Mark Diacono in his cookbook Sour: The Magical Element That Will Transform Your Cooking.

Perhaps no one knows how to maintain a steady buzz of acidity better than a chef. “Sour can be in a cocktail, a main course, a dessert, a snack—it’s everywhere,” says Rob Rubba, the executive chef of the vegan tasting menu restaurant Oyster Oyster in Washington, DC. Rubba uses a diverse assortment of underripe fruits and ferments in his cooking, like a recent marigold vinegar experiment that worked unexpectedly well. “It has this stringent yuzu vinegar [flavor] that is really fun and funky,” he says. Not only do chefs lean on natural acids, but ingredients like powdered citric acids are also used to achieve vivid, perky flavors, like a dusting of malic acid on a noticeably tart apple cider donut at Smithereens in New York City. “That’s the fun part,” says Rubba. “Making it feel alive.”

All this talk about chefs tinkering with flavor might have you questioning reality, a familiar concern in the age of AI. But our bodies keep score, and our mouths feel what’s real.

Speaking of bodies, the literal mouthwatering response to the mere suggestion of sourness might also explain why the internet has become a hotbed of videos of people enduring the repelling/compelling taste of sour foods like pickles and, especially, candy. “You can visually see the strong taste response, which makes it more engaging,” says Charles Spence, a professor of experimental psychology at Oxford University. Spence goes on to describe the simulation as an “empathetic physiological response,” like next-level ASMR.

From sour grapes to dill pickle–flavored chips and every puckering moment in between, people can’t seem to get enough of this very real, very bracing trend in food.

The collision of sour candy with the online medium has certainly inspired a new generation of candymakers. Caleb Phelps is the cofounder of SourBoys, a Texas-based confection company that sells gummies on a one-to-five scale of sourness (blue raspberry strips, which are slightly more sour than Sour Skittles at level four, are a top seller). Phelps is a professional YouTuber, but he started a sour candy brand because he felt it had the right aesthetics for high engagement. “I don’t know how it tastes, but I know I want to eat it,” says Phelps, describing the feeling of watching people eating sour candies online.

Companies like SourBoys can also be seen as derivatives of extreme chili pepper fandom, where customers brave increasingly spicy levels of hot sauce to test their threshold for pain. Spence, the Oxford professor, points out that these are the literal opposite of comfort foods. Or maybe it’s all just part of a shift toward extreme flavors, where everything is becoming bolder, spicier, more intense. And because most sour candies get their shock factor from powdered citric or malic acids, it’s relatively easy to scale those ingredients and amp up the sourness without much of an adverse effect. (Dentists might disagree, though, as foods with a pH of around 4 can start to wear away your enamel.)

Ultimately, as more of our lives revolve around digital spaces, the trend of living vicariously through sour foods, both online and off, is still highly relevant—for now. “Food is a fashion business,” says Christopher Anderson of the online retailer Modernist Pantry, which sells culinary-grade acids (he confirmed that sales of acids have increased over the years, in part driven by the rise of gummy edibles). Phelps likened it to the popularity of bacon 20 years ago.

Meanwhile, food companies are cashing in. Warheads, an OG super-sour candy brand from the 1990s, recently collaborated with Fruit Riot! to make a watermelon-flavored line of frozen grapes, which has the added bonus of seeming kind of healthy. To lure nostalgic millennials, a company called Iconic Candy bought Altoids Sours and then relaunched it as Retro Sours earlier this year. In the beverage sphere, the flavored syrup brand Monin declared yuzu the flavor of 2025. And finally, the viral online snack company Padiano’s Kitchen sells straight sour powder, for the fiends who want to tart their hearts out—video promos show founder Paden Ferguson pouring it over everything from carrots to popcorn.

And we, the customers, are buying it. In one particularly relatable video, as Ferguson pours his mix of citric, malic, tartaric, and ascorbic acid powders over a chocolate chip pancake, a comment from a fan named Rebecca Brown hovers in the corner of the screen: “Stopppp 😩 take all my money,” it reads. As the powder free-falls like snow on the screen, I feel a familiar prickly, mouthwatering desire take hold.