How a quintessentially American condiment became a quintessentially Japanese condiment beloved in America

You couldn’t fault Toichiro Nakashima for thinking that mayonnaise was a key ingredient, if not the defining one, of American cuisine when he visited the United States for eight months in 1915.

Crack open an American cookbook from the early 20th century, and there are likely multiple recipes for mayonnaise-enriched coleslaw and deviled eggs; the burgeoning lunchrooms of American urban centers served sandwiches with chicken salad, tuna salad, lobster salad, ham salad—calling something “salad” simply meant it was bound by mayonnaise; and Waldorf salad, otherwise a jumble of fruits and nuts if not for mayo, was served on the finest restaurants’ silver, including at its namesake, the tony Waldorf-Astoria hotel in New York City.

Nakashima, then a young intern for Japan’s Ministry of Agriculture and Commerce in Washington state, encountered mayonnaise for the first time mixed with canned salmon and finely chopped onion as well as in potato salad. He returned to Japan with a new infatuation—and with business in mind.

In 1925, Nakashima introduced Kewpie brand mayonnaise to the Japanese market, with a recipe he painstakingly crafted utilizing only egg yolks for extra richness, vegetable oil, rice vinegar, and MSG, a recently developed household seasoning, for umami. For the brand’s trademark, he purchased the Japanese rights to a doe-eyed doll known as Kewpie, based off a 1909 cartoon by the American illustrator Rose O’Neill, which was just becoming popular in Japan.

While some customers initially mistook the product for hair oil, it—and mayonnaise more broadly, by extension—soon became entrenched in Japanese cuisine. In 1958, Kewpie Corporation phased out glass containers for lightweight, squeezable plastic bottles with red caps, and the now iconic packaging has changed little since then. It’s found in virtually every household in Japan, it’s mixed into every Japanese potato salad and convenience store sando, and it tangoes with dancing bonito flakes and Bull-Dog sauce on every plate of okonomiyaki and takoyaki served from Hokkaido to Okinawa. It’s now sold in 79 countries and regions worldwide, including the United States, its spiritual birthplace, where it sold four million bottles in 2024.

One hundred years after its founding, Kewpie is synonymous with Japanese-style mayo worldwide. And in the United States, it’s become idolized among food writers, indispensable among chefs, and symbolic of a certain Asian American pride.

“It’s very rich; the color is very buttery-yellow; it’s savory, vinegary—it’s just an intense mayo on all fronts,” says Elyse Inamine, a New York City–based journalist and author. Last summer, she got a call from her agent to gauge her interest in working on a cookbook about Kewpie mayonnaise.

“I was like, ‘Oh my gosh, I have to work on this—I always have a bottle in my fridge,’” she recalls.

The book, For the Love of Kewpie: A Cookbook and Celebration, written by Inamine and chef Jessie YuChen in collaboration with the Kewpie Corporation, will be released this October from Workman Publishing Company. It includes detailed chapters on Kewpie’s evolution throughout the 20th century, a mini biography of Nakashima, interviews with Kewpie employees, and unexpected recipes that utilize Kewpie as a binder in dishes like carbonara or meatballs, as a marinade for fried chicken, and as a coating to prevent clumping in fried rice.

YuChen, a New York–based chef and writer of Taiwanese heritage who developed the recipes for the cookbook, says, “I learned a lot about how versatile Kewpie can be. We even have a dessert chapter,” where the creamy condiment provides a savory edge in a chocolate cake and adds loft to fluffy Japanese pancakes.

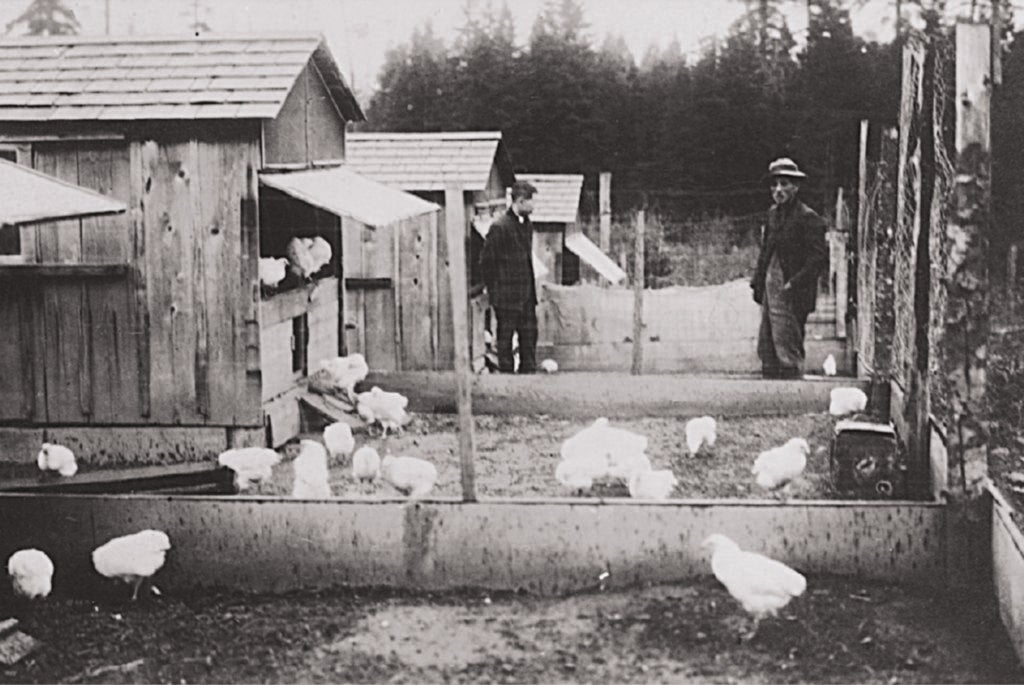

Kewpie is and has been unique in the mayonnaise market in a few ways—from a culinary standpoint, perhaps its most distinguishing feature is its use of only egg yolks. Most American mayonnaises are made with whole eggs, and they have a more pallid color as a result. Each 450-gram bottle of Kewpie mayo contains about four egg yolks. Recognizing the importance of high-quality eggs for its product, Nakashima established an egg farm just for Kewpie mayo in the 1930s. When faced with the question of what to do with the unneeded egg whites—which Nakashima called “a grave issue”—the company began selling them to cosmetic and pharmaceutical businesses, ensuring the byproduct wouldn’t go to waste.

Kewpie Corporation also started making its own vinegars, initially collaborating with Japanese rice vinegar breweries and eventually launching its own offshoot brand, called Kewpie Jyozo Co., in 1962 to make apple and malt vinegars. Ironically, though Nakashima was looking to nail a “Western” flavor profile with his vinegar, many say that Kewpie mayo has a bolder, more vinegary flavor than most American mayonnaises, which is balanced by the use of MSG, or monosodium glutamate. (It should be noted that there are slightly different formulations of Kewpie mayo made for markets around the world, including a US-produced version, launched in 2016, that does not contain MSG and that some find to be inferior; however, the original Japanese-made version with MSG is also widely available in the United States—this Japanese Kewpie mayo is the one referred to throughout this article.)

Kewpie was initially sold in glass jars.

Also notable is its packaging: Kewpie’s soft, squeezable bottle keeps out oxygen even as the majority of the mayo is dispensed, rather than sucking air back in (as anyone who’s emptied half a bottle knows, it slumps over rather than standing upright), thus preserving the freshness of the mayo. The default nozzle works great for squiggling neat stripes, and tucked inside each red cap is an additional star-shaped nozzle that can be switched out in order to pipe pretty bursts of Kewpie, à la cupcake frosting.

Inamine says that the more she researched Kewpie’s history and ethos for the book—how Nakashima fostered a culture of collaboration and innovation, how the company prevailed in the face of challenges over the decades like a five-year hiatus following World War II and domestic competitors—the more she admired it, which isn’t something that always happens when peeling back the layers of major food brands.

As a Japanese American, Inamine grew up in what she calls a very Westernized household in Valencia, California, and her family didn’t have a place for Kewpie mayo on the refrigerator door like she does in her own home today. Inamine estimates it was sometime in the 2010s when the product became a constant presence in her life, after it blew up among US-based chefs. But through her work on the cookbook, her parents have become huge fans of Kewpie mayo, and her mom even cried while visiting the Kewpie museum in Japan earlier this year.

“Groceries are very intimate—they’re something that we bring into our homes and feed our loved ones with, and I think people don’t even realize how sentimental they feel about grocery products until they’re removed from their context,” says Stephanie Shih, a Brooklyn-based artist.

Shih created a clay sculpture of a Kewpie mayo bottle in 2021, as part of a series of works featuring Asian pantry goods that she began working on in 2018. She didn’t anticipate the outpouring of emotion her work would elicit from viewers; soon people were sharing unsolicited memories with her about their father on his deathbed, spurred by a sculpture of a tin of fried dace.

“There were a limited number of products that were being imported to the United States in the ’80s and ’90s for Asian immigrants, so we all knew the exact same brands and had memories of those brands,” she says of the impetus for her series.

Nishifu Farm, Kewpie’s egg farm in Tokyo circa 1934.

Growing up in New Jersey among children of immigrants from many Asian countries, Shih was exposed to many of these foods lurking in cupboards, like Maggi seasoning and Ovaltine. Shih was particularly interested in Kewpie’s story of East-West influences that didn’t follow a straight line: “Just the use of a Kewpie doll is so fascinating—how this American cartoon comes to symbolize this Japanese version of a French food.”

Although her Kewpie bottle sculpture sold immediately after it was included in a solo exhibition in Miami, Shih says she frequently receives requests to make more in the same style.

Kewpie mayo has become a nostalgic favorite even when it’s not technically being used. Vegan baker Annie Wang has been retooling classic Asian pastries at Little Moon Bakehouse in Oakland, California, since 2017, and she makes her own Kewpie-inspired vegan mayonnaise to top a corn hot dog bun. “I thought it would make the pastries more well-rounded and more true to their origins if I were to make a vegan version of Kewpie mayo,” she says, adding that the vegan mayonnaises she’s found in American grocery aisles didn’t have the bold and tangy flavor she was looking for. And although Kewpie Corporation does make a vegan mayo today, Wang enjoys the control that comes with developing her own recipe, which uses oat milk and olive oil, given her customers’ various dietary restrictions.

“It’s my default mayo,” says Yasmin Fahr, a cookbook author and recipe developer currently based in Menorca, Spain—an island that is incidentally the birthplace of mayonnaise, according to local legend.

“There’s a respect for Kewpie.”

When creating recipes, Fahr says she is looking to use a minimal number of ingredients, but she requires that each of them carry a lot of weight in a dish. The richness and full flavor of Kewpie mayo, she says, makes it feel like more than a mayonnaise and rather “an integral part of whatever it becomes,” she says.

In her cookbook recipes and the recipes she’s published online—such as Paprika Chicken and Potatoes for NYT Cooking—Fahr typically writes “preferably Kewpie brand” when listing mayonnaise as an ingredient. Did editors ever think that was weird, or try to push back? Absolutely not, Fahr responds with a laugh. “I think most of my editors understood and were like, ‘Oh, this is wonderful,’” she recalls. “There’s a respect for Kewpie.”

Emi Boscamp, a senior food editor at Today.com, says that she’s seen Kewpie mayo quickly transform from a pantry item that was primarily essential within her Japanese American community into a widespread cultural phenomenon during her lifetime. She grew up eating egg salad and tuna salad sandwiches made with Kewpie mayo that her family bought from the Mitsuwa Marketplace in Edgewater, New Jersey. “Now most of my friends who cook have it,” says Boscamp. She’s seen people slather it on their Thanksgiving turkey like a stick of softened butter and stir it into instant ramen soup as a “creamy” hack.

None of these uses are particularly Japanese—but then again, neither was egg salad or potato salad before Kewpie mayo came along in 1925. When the brand founded a branch in the United States in 1982, it was, in many ways, a “full-circle moment” for the company, writes Inamine in For the Love of Kewpie. A quintessentially American condiment was recreated as a quintessentially Japanese condiment, then distributed and beloved in America. Over the last year, the brand has been busy celebrating its centennial through various campaigns in Japan—including a sweepstakes to send lucky customers on a four-night trip to the island of Menorca—and in the United States, where it gave away 100 bundles of swag and gift cards galore. And, of course, there’s the book.

Where will the next 100 years take the company and its flagship product? Executives at Kewpie Corporation who responded to my questions through email pointed to an organic mayonnaise, which was recently released at Sprouts Farmers Market locations in the United States. This, along with a line of salad dressings that launched in 2014 and the aforementioned MSG-free and vegan mayonnaises, represent a relatively new category for the hundred-year-old business: products developed specifically for the US market, from a well-known Japanese brand. Will they be embraced the way Kewpie’s original mayonnaise has been? Only time will tell.

Photos excerpted from For the Love of Kewpie by Kewpie Corporation, Elyse Inamine and Jessie YuChen (Workman Publishing). Copyright © 2025. Photograph courtesy of the Kewpie Corporation.