For 23 years, chef Angel Jimenez has drawn barbecue pork devotees to the South Bronx. This summer, the party is heating up again.

It’s an overcast, temperate Saturday morning in the middle of May in the South Bronx. The Yankees, who play in a glittering $2 billion magnet that serves as the borough’s main attraction, are on a five-game winning streak, attempting to pull away with early control of the American League East, and they will be facing the White Sox in their stadium several hours from now. I’m ten minutes away from home plate, in a trailer at the intersection of Wales Avenue and East 152nd Street, boxed in by brutalist housing built by the city in the early ’60s. A car with an augmented sound system is parked on the corner with its doors open, blasting Latin trap and Polo G as a crew of early twentysomethings with neck and brow tattoos—some with thin facial hair seemingly drawn in fine tip marker, others in warm-weather sheisties—dance, slapbox, smoke weed, and drink on the curb in front of a bodega at 9 a.m.

Driving into the South Bronx—the portal connecting New York City to Westchester, Connecticut, and New Jersey—feels like traveling through the dense guts of a great beast. It’s a digestive tract composed of on-ramps and approaches to elevated superhighways, of bridges and tunnels, of roads to elsewhere at the expense of what has been cast as a way-station neighborhood, sending an unsubtle message from Robert Moses that there are more important places to be. But we are here, below the swarming network of weekend commuters, and Chef Angel Jimenez is prepping for a day of service at his one-of-a-kind restaurant slash weekly block party, La Piraña Lechonera.

Jimenez is in his late fifties and has a bullet-shaped head jutting between broad shoulders like a dorsal fin. He has the ringed eyes, complexion, midsection, thick arms, and coarse hands of a man who has enjoyed life’s carnal pleasures—and worked very hard to enjoy them. He’s wearing Carhartt work pants and a pava, a brimmed woven hat made with strips of palm that appear to form a halo of straw flames (or thorns) on its wearer’s head. The hats are historically connected to the uniform of the jíbaro, hard-laboring farmers who live off the land in Puerto Rico. This is not so different from the chef’s childhood. At 14, he got his first job cutting sugarcane alongside his father for $3 an hour in his native Aguadilla, a coastal city on the island’s northwest corner.

Jimenez relates this history to me with a grin, a Heineken deuce bottle in his hand and a half-smoked, clipped joint sticking out of his mouth. He’s walking me and his precocious five-year-old son, Samuel, through the preparation of rice, guineos (green bananas), and the multiple elements that compose his seafood salad (peeled shrimp, frozen containers of picked crab, and precooked octopus, all prepped and held separately) for service. “I’m doing with him what my father did with me,” he says.

Angel Jimenez in his element.

Angel both is and isn’t performative. He’s an organic, extroverted showman; his resting speed is most people’s 150 miles per hour. He’s instantly warm and familiar with strangers, loud and gregarious. Angel is what social media content farmers would refer to—and exploit—as an “authentic New York character.” I first met him last August. I was in the borough to cover the Hip Hop 50 celebration, and I stopped by La Piraña for lunch. The line was modest, but getting a plate of Piraña’s signature dish—lechon, or roast pork doused with garlic sauce—took two hours for reasons I couldn’t understand at the time.

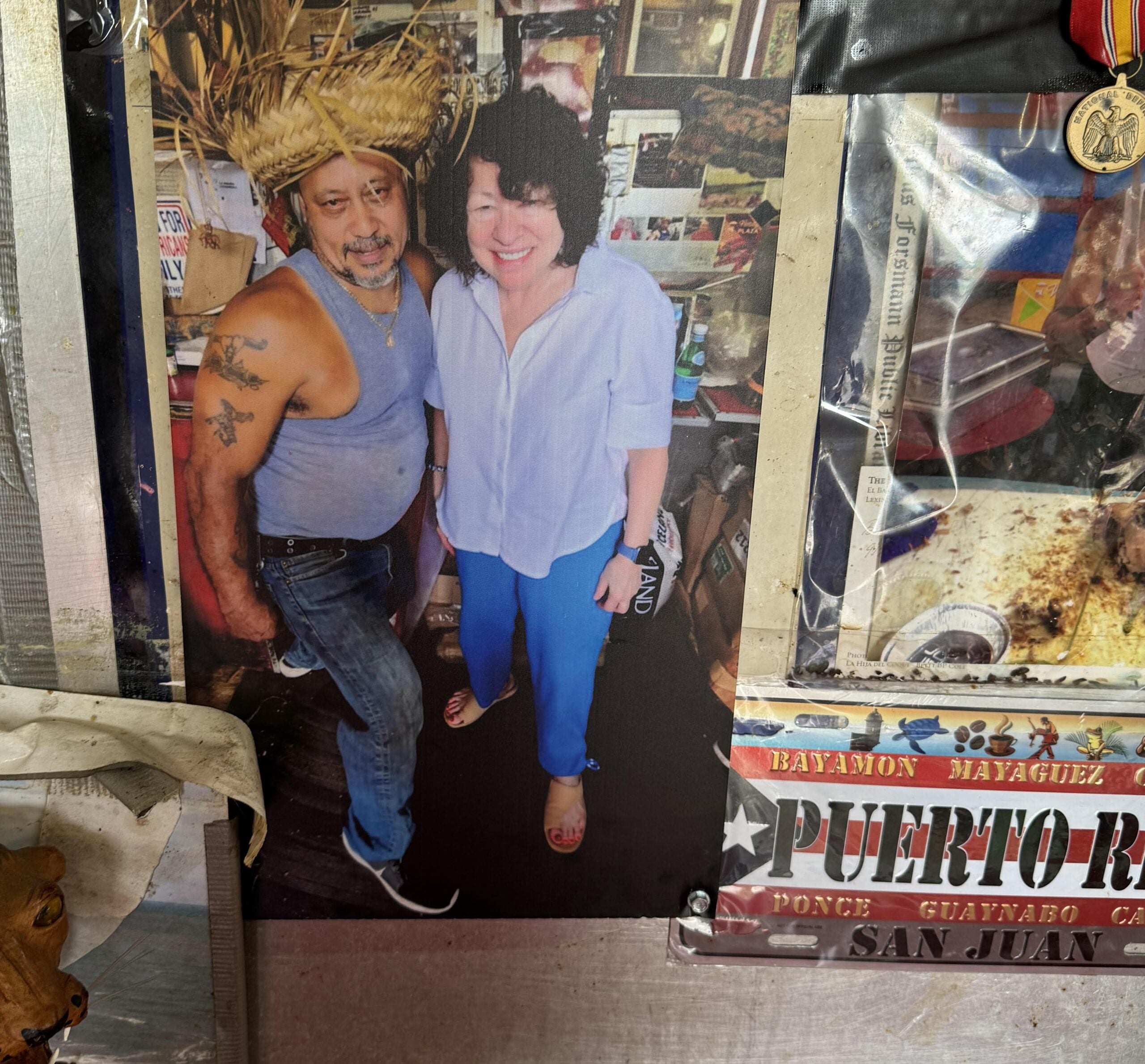

While I was waiting, Angel pulled from a Heineken and chatted up the crowd, occasionally fighting with an inebriated local woman he clearly had some history with, and offhandedly mentioned to me that earlier that day he had served a plate of lechon to Supreme Court justice Sonia Sotomayor. The story had the flavor of a guy talking elaborate shit from his station at a dominoes table on a street corner, but when I checked him on it, Angel pulled out his phone. Sure enough, there was a selfie taken that day, posed with the justice from Soundview.

When it was finally my turn to order, Angel had run out of rice, guineos, and seafood salad, leaving only the lechon. I shared it with my wife, passing the hefty clamshell back and forth in the car, eating roast pork off our laps with a plastic fork. It was somehow one of the best meals I had last year, and I haven’t been able to shake the experience since.

Jimenez has the ringed eyes, complexion, midsection, thick arms, and coarse hands of a man who has enjoyed life’s carnal pleasures.

The late historian Cruz Miguel Ortíz Cuadra writes that whole roasted pork has been a staple of Puerto Rican cuisine since the early days of Spanish colonization five centuries ago. The first pigs in the Antilles were brought to the island by Christopher Columbus in 1493 as part of his second voyage. The pig, resilient, cheap, and plentiful, with a feral breed running wild in the island’s mountains and reproducing organically, became the protein of the masses, raised and hunted by laborers and bosses alike. Slaughtering and preparing pigs, butchering their meat, and making blood sausage and cracklins all took on a communal aspect. A pig roast was standard fare at celebrations and weddings, a foodstuff that denoted good fortune and good times—a tradition carried on by Piraña.

Angel’s first love was the ocean. He was a born swimmer and a determined fisherman in his beach town, Aguadilla, which is where he got the nickname “Piraña,” for the infamous freshwater omnivore. He learned how to roast pork from his parents, but, just as important, they taught him that selling food could be a lucrative side hustle. When his father wasn’t cutting sugarcane, he’d set up a grill on the beach and barbecue chuletas and freshly caught tuna for locals and tourists. Angel has never worked in a restaurant in any professional capacity, but he is a consummate New York City street entrepreneur, a live-in super in his building up the street from La Piraña who also works as a union HVAC technician five days a week, primarily servicing the condensers in Hunts Point that power the teeming Bronx market’s cold spaces.

And, during the warm weather months for the last 23 years, on Saturdays and Sundays, he sells roast pork out of a trailer he bought off a friend and modified himself to serve as a makeshift kitchen. He claims it’s a financial necessity. “I got nine kids, chulo,” he tells me (the chef calls everyone “chulo,” and everyone who I met that he knew before that Saturday calls him “chulo” as well), in addition to five grandkids, or, as he refers to them, “nine kids plus tax.” And while I’m sure he needs the money and the restaurant is a welcome, regular shot in the arm for his checking account, I suspect that added income isn’t the sole, or even the greatest, motivating factor behind his dabbling in the food service industry.

Supreme Court justice Sonia Sotomayor has made Piraña visits.

Every Friday during baseball season, Angel picks up four or five 120- to 150-pound whole pigs from Hunts Point, depending on how busy he expects the weekend to be. He rubs them down with a seasoning blend that was the only part of the process he insisted on keeping to himself (but you can find videos of it online) and butchers each pig into three or six pieces (the front quarters, ribs, and hind quarters, either splayed or halved).

Around 4 a.m. on Saturday and Sunday mornings, six to twelve chunks of pig on four sheet pans go into an old double-decker Blodgett bread oven on the sidewalk a half block down the street from the trailer that looks like it survived an atomic blast and could survive another one. Angel bought the oven used from a shop on the Bowery twenty years ago for a thousand dollars. The pig roasts in the oven at 300 degrees Fahrenheit for eight and a half to fourteen hours, undisturbed aside from occasional visits from Angel to drain the pooling rendered fat off the pans into a five-gallon plastic utility bucket. He begins selling plates at 12:30 p.m., and by 5 or 6 in the afternoon each day, both pigs will be gone.

Barbecue is a depreciating asset, one of those “lose a third of its value when you drive it off the lot” situations. It’s one of several foodstuffs that demand urgency. There are some popular barbecue palaces in New York that our natives have dismissed as “mid,” that they forfeited to hordes of TikTok food tourists years ago. They’d be shocked if they could be at some of these establishments when the brisket first emerges from the smoker, covered in glistening bark, the hunk of cow belly quivering, juices flowing in rivulets erotically down the muscle face when first sliced in half.

A pig roast was standard fare at celebrations and weddings, a foodstuff that denoted good fortune and good times—a tradition carried on by Piraña.

What these people don’t understand is that the crush of New York City real estate, the pressure of low-yield barbecue’s ever-slimming margins as meat prices continue to rise exponentially, and the ambition of these restaurants’ owners—who long ago decided a compromise was necessary—force the meeting of demand, which doesn’t allow for you to experience this product in its platonic form. Many of the city’s barbecue joints overproduce for every contingency to ensure they never sell out (no pun intended).

The brisket I described is just one hunk in a fleet coming out of an industrial smoker, which cools on sheet trays, is wrapped in plastic, and is left to sit, often for days in a large walk-in fridge, until the laws of FIFO (First In, First Out, a necessity of restaurant asset management) allow for its number to be called, at which point it is reheated in a combi oven, then left to sit in a steam table, the flesh exposed, for hours, drying out. When the meat finally gets to the guest, they are right to sniff it, douse it in a sauce to reanimate it with moisture and flavor, and deem it “just fine.”

This is what makes La Piraña special. It’s New York City’s greatest smokeless barbecue restaurant, and it’s in the same league as the mythical Texas temples that open at an appointed time and sell slowly to a line throughout the day, delivering the freshest possible product at its moment of inception, then closing for the day whenever they run out. The essay you are reading is only adding to a rich history of fine journalism dedicated to La Piraña over the years, and as a result, Angel will never suffer from a shortage of demand.

He could invest in equipment that would allow him to produce more food every weekend. He could hire a staff and expand his hours. I asked him if he’d ever been approached by the usual coterie of investor types looking to capitalize on his success, as nearly every piece ever written about Angel suggests his ambition is to one day open a restaurant. “Sure. But I don’t want partners. Partners mean problems,” he admits, as he dumps steaming rice into a deep hotel pan before “service.” He seems uninterested in the expectations and oversight that come with a structured business and entirely comfortable running his restaurant on his schedule, his way. It is antithetical to any modern coherent reading of capitalism in New York City’s restaurant industry.

The door stays open on La Piraña’s trailer, and every 10 to 15 minutes, a steady chorus of neighbors pop their heads in to say hello, play with Samuel, and sneak a taste of the seafood salad. Angel composes a sample for me in a translucent seven-ounce cup. It’s not a symphony but a cacophony, an orchestral stab of flavors and textures. The braised shredded crab coats everything. The firm chew of shrimp competes with the softer chew of the octopus, which competes with the even softer chew of the whole olives from a jarred salad. There’s the crunch of the raw onion and peppers. And there’s the current of tri-heat provided by a dousing of Red Devil pepper sauce, chopped chipotle peppers, and the garlic sauce (whole raw garlic cloves blended with vegetable oil), all backed by the sturdy baseline of a synthetic umami-rich broth, studded with chicken bouillon and sazón that reminds you of something you’d sip to ease a swollen throat on a sick day when you were a kid. Forgive the cliché, but it’s a dish, in its balance of chaos and comfort, that explains a chef.

As Angel prepares these elements and the rice, we make small talk, and his stance at his station is loose, shifting his weight back and forth, pacing in place to the music in his head. He works on autopilot, entirely by feeling, with no timers for any of the multiple pots he has going at any time. Every element in the trailer can be utilized. An empty, thin cardboard sazón package can be a cutting board; an empty tin of chipotles can be a measuring cup. He stops to sharpen an ancient knife with a long, flat steel file and occasionally thinks to wipe down surfaces with his all-purpose kitchen rag. It’s of a piece with the space: the broken-down produce boxes that serve as floor mats in the kitchen; the old, stomped-out, grease-sodden square of frayed carpet on the customer-facing side of a homemade counter; some odd plastic animal decorations Samuel utilizes as toys; the walls papered in a scrapbook collage of old-press, pixelated pictures clearly printed off of a phone camera and cards quoting bible verses, commemorating the lives of deceased friends and family members. His restaurant tells a random and cohesive story in the same way your apartment does.

The line begins to form around 11 a.m. A middle-aged Latina woman in street clothes and an NYPD windbreaker is one of the first guests, and she’s brought a coworker, a tall white man who is a first-time customer. She looks over her shoulder, down the trailer steps and back at the forming line, and marvels, “Look at the diversity,” referring to the seemingly hand-chosen-by-central-casting New York collection of people who clearly live up the street and don’t feel like cooking today. And also seeded with Polish tourists staying in Columbus Circle, wrinkled Filipino downtown affluent artist types, and young white and Black would-be food influencers who traveled from Astoria referencing their Infatuation apps. Angel’s longtime friend and neighbor Will Valentine, a neatly attired Puerto Rican immigrant who clearly enjoys Angel’s food, is next to me, filming it all on a live feed for around 250 viewers at any given time on his 50,000-follower TikTok account, which doubles as the restaurant’s unofficial social media presence.

Angel asks all the obvious first-timers how they heard about the restaurant. They all say the New York Times, referring to Pete Wells recently naming La Piraña the fifth-best restaurant in the city. “New York Times has me at number five right now. The people over me? Number four? To eat there, you need 300 bucks,” he says, referring to what is arguably the crown jewel of Rita Sodi and Jody Williams’s Greenwich Village haute empire, Via Carota. “My food costs $20 or $30. You can’t eat better for less than that in New York.” And he’s right. (Several days after my visit, La Piraña was moved down to sixth place, displaced by Blanca, the impossible-to-get-into, several-hundred-dollars-a-head tasting menu spot in Bushwick, only serving to reinforce his point.)

Angel uses his phone to play a blaring soundtrack of brass-heavy salsa songs about love and lust and heartbreak and passion through a speaker and trudges up the street to grab the first tray of pork. He can gauge the doneness by sight, so with a glance at 12:40 p.m., he knows we’re ready. The first tray is the ribs, as the middle section is the thinnest, most tender meat that cooks the fastest, and it’s Angel’s favorite. From the top of the oven, he cuts me a hunk, and I understand why. The cuero, or lacquered skin, is a lard pie crust, starting with a shatteringly crisp exterior an inch thick, getting softer and richer with each layer of derma. You can only enjoy a few indulgent bites as you feel your heart rate slowing, but if you’re into that genre of excess, it’s transcendent.

The flesh beneath is steaming out of the oven, glossed with fat and pig liquor, shredded without any shredding necessary, in a liminal state between solid and liquid. It wants a starch to soak, perhaps some carbonite fried yellow rice with canned pigeon peas out of Angel’s battered rondeau, or some boiled guineo, or some slices of bread painted with drawn garlic butter and caramelized in a sandwich press, but it’s an intense rush in its pure form, eaten out of my palm as I stand at an angle to protect my clothes from raining grease on a Bronx sidewalk.

Angel comes down the street from the oven carrying a steaming third of two pigs on a sheet pan. He stops at the foot of the trailer steps so that the many camera phones—on what has become a Supreme capsule drop line—can eat first, a cross between displaying a cut of beef before grilling it at a steakhouse and lowering the lights as your family wheels out a cake with lit candles on your birthday. After Samuel gets the first plate, which Angel insists on dousing with Red Devil and garlic sauce to educate, train, and challenge his palate, the customers begin filing in and placing their orders.

The following is a partial list attempting to explain why it takes so long to get food at La Piraña:

- Ordering, which can take a while, trying to both hear and make yourself heard over the blasting salsa, then hoping the order is translated to what is plated in your clamshell, which, when it doesn’t, may need to be discarded and replated.

- Service, which is Angel whacking at the slab of roasted pig through the cement layer of chicharrón and bone with a machete, pork detritus quite literally flying in the air like he’s a drunk Swedish Chef from the Muppets, serving the requisite gleaming, striated pork nugget sample along with laughably enormous portions in each several-pound clamshell, all while making small talk and taking pictures.

- Friends and regulars know to come around the trailer to the back window to order and skip the line, which obviously slows things down.

- Angel takes sporadic trips up the street to check on the remaining trays of roasted pork, leaving the trailer unattended, which often coincide with breaks to smoke a joint.

If any of this might bother you after more than an hour in line, I’d suggest finding somewhere else to eat. Because, rather than the mark of a disorganized amateur, this seems to be the exact style of service intended at the exact pace Angel designed. He is entirely uninterested in moving things along, often talking with guests for longer than the guest seems to want to after their long wait to eat. He never checks a watch, uses a scale, or measures anything, but, including joint breaks, everything moves like clockwork. I could see some logic in this being purposeful, to cultivate a line and a mystique, but it’s also inconceivable that Angel would be interested in this degree of preconceived anti-advertising calculation.

The flesh beneath is steaming out of the oven, glossed with fat and pig liquor, shredded without any shredding necessary, in a liminal state between solid and liquid.

Angel simply appears to have a muscle memory and an internal clock that keeps perfect time according to the schedule he’s settled on. Before service, Angel told me that each tray of pig yields about 25 orders, so I counted, and because his process is so unscientific, and because he gave away at least two orders in ice-cream-scoop-size samples, I couldn’t believe the first tray came out to exactly 25 orders, including Samuel’s.

It’s done little to dissuade the locals, the tourists, the writers who have been praising this process, and its chef for just shy of a quarter century. Everyone tips, but the regulars pay tribute, leaving deuces of Heineken on the countertop sheathed in a brown paper sleeve. No one made the mistake of buying any other brand. A microeconomy has sprung up around the line. A half block down, a middle-aged Puerto Rican man named Francisco sets up a tent (with Angel’s blessing), selling a menu of fried foods (empanadas, catfish, meat-stuffed guineos) for the hungry and impatient to snack on while waiting for the main event. Across the street, a bodega on the corner is bustling, serving as bathroom, bar, and bake sale for the line.

Their patience makes sense, of course because the food is so fucking good, but the theater is an important part of the appeal. Angel gave several people discounts, seemingly at random, and told a regular who had been waiting for two hours and said he’d return tomorrow, who was holding cash in hand and trying to give it to him, to come back and pay him on Sunday, for no reason I could fathom. I did some back-of-the-napkin math, and taken at his word, Angel pays $3 per pound on 120- to 150-pound pigs, so let’s say each pig costs roughly $400.

He sells plates of pork and rice for $20 (we’ll leave the $8-ish seafood salads out of this) and preps two pigs a day, which yield roughly four trays, and if 25 orders per tray holds steady, that’s 100 plates. So if you exclude rice, condiments, and paper goods, just off the pig alone, the $800 Angel spends and the $2,000 he makes yields a 40% food cost, which is fine but would get a chef at a serious restaurant fired on the first P&L review, particularly when you consider that the $1,200 per day (plus tips and Heinekens) is a fraction of what he could make, at the rate he serves, at the incredibly low price he sells at, and without the portion control or increased prices he could easily institute. There are easy and obvious versions of this restaurant that maximize the profit and serve more people far more efficiently; it’s the anti-Chipotle.

The plate of the day on a recent visit.

As if hearing my inner monologue while struggling with that equation in my English-major head, an emotionally unstable man named “E”—who was drunk when I got there that morning, played with Samuel for a while, then left—shuffles back into the trailer. Chef hands him a free plate containing the entirety of the menu, because, as he told me that morning, they had grown up together. As he does so, he proudly advertises it to his paying customers watching, telling them, “Money is not everything in life!” Which is both clearly a bit and something he’s proving he means throughout service in front of our eyes.

Angel is also a tireless maniac with no kill switch. I’m several decades younger than him, slept more, drank less, and didn’t work at all during the day, while he worked incredibly hard—and six hours into service, I was exhausted, and he was moving with the energy and humor of Josh Hart in the first quarter. After a few hours, I’d seen the routine with the trays of pork a few times and asked all my biographical questions, and all the “real reporting” was done, so I leaned against a wall in the trailer and just watched him work for a while.

And somewhere between my second and third Heineken deuce, it occurred to me that Angel likes to cook in the exact same state I do: with a drink going somewhere just off his cutting board, with a great playlist in the background, in no particular hurry, surrounded by old friends and strangers who quickly feel like old friends as everyone snacks and laughs and talks shit at a party you hope will never end. His “business” is one of the more ingenious ways I’ve ever seen someone figure out how to make money doing something they’d happily do for free. He’d told me as much earlier. I just dismissed it. I mistook his sentiment for boilerplate pablum that any standard, cynical, money- and ego-driven chef will tell you when asked what their restaurant means to them. Now I’m not so sure.

It happened while I was trying to eat a steaming piece of rib meat next to his massive, freestanding oven up the block. I took my first crunching, melting bite and closed my eyes, probably looking crazy as I was both appreciating it and trying to figure out how the fuck I could possibly describe all of the insanity I was tasting and experiencing in writing. Chef Angel read my exultant face, drawn tight with concentration, and broke the silence. “See? That’s it. For me, it’s love. People love me. People come from all over the world to eat my food, for the experience. That’s why I do it.”

Photos by Abe Beame