What makes a good club sandwich? Ask the guy who’s eaten them everywhere, from Paris to Phnom Penh.

Evan Saunders has eaten more than 200 club sandwiches—and those are just the ones he’s written about. As the voice behind Club Sandwich Reviews, a blog dedicated entirely to the iconic layered sandwich, Saunders has traveled hundreds of thousands of miles with one objective in mind.

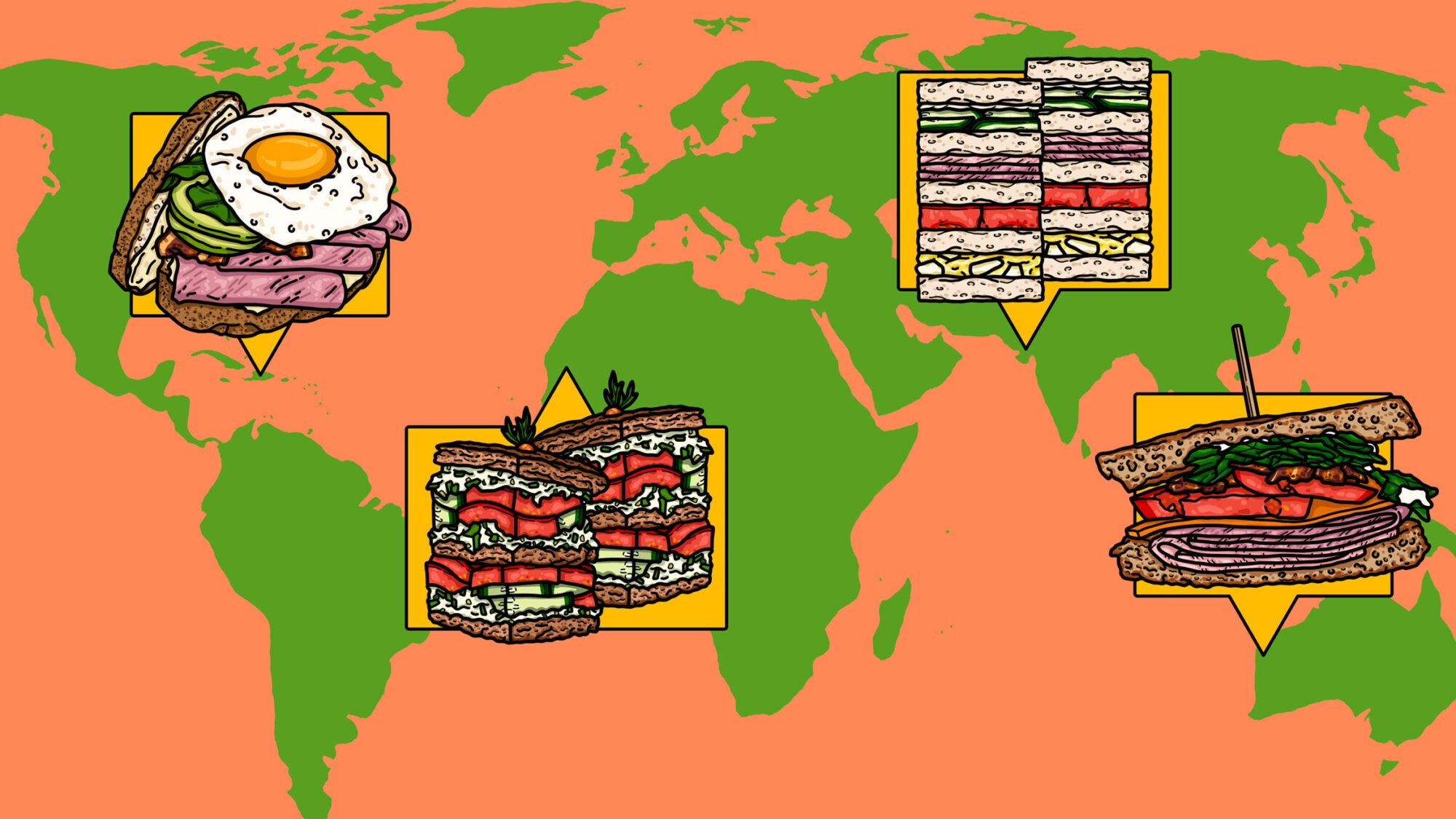

“My goal is very much to be the world’s leading expert on the club sandwich,” Saunders boasts. He’s definitely on his way. Over the past decade, the California native has rated and reviewed clubs in 26 countries—sandwiches he’s eaten over the desk in modest hotel rooms and poolside at five-star resorts, at fast-casual eateries and Michelin-starred restaurants, and at airport kiosks before overseas flights.

“It started while I was living in China and traveling a tremendous amount,” says Saunders, who works in the tourism division of a research and marketing company in California, noting that he loves trying local dishes but sometimes craves American comfort food when he’s on the road for an extended period of time. (Before COVID, he clocked 200,000 miles a year.) To him, that meant club sandwiches, which, “surprisingly enough, are available at almost every hotel I’ve stayed at in the world.” Undertaking the process of eating, documenting, and reviewing them all became a way to chart the evolution of a piece of Americana that was carving out a place in people’s hearts around the world.

A cartoon portrayal of the sandwich might involve a diagonal-cut, multilayered assemblage of toasted white bread, bacon, and sliced turkey or chicken, held together with frilly toothpicks, but for Saunders, every one of these elements is negotiable. There was the club sandwich with sweet peppers and Russian dressing served at an outdoor café in Phnom Penh, Cambodia; the one layered with ripe, indigenous Hawaiian tomatoes, onions, and avocado at a hotel in Honolulu; the expensive stack of smoked salmon, roe, and cream cheese at a Michelin-starred kitchen in Paris (“at $60, I honestly was expecting something a bit more,” he said).

By 1972, James Beard was coming down hard on what he considered to be “bastardized” versions—including touches like a third piece of bread in the center or the use of turkey instead of chicken.

The club sandwich has been diligently (and sometimes emphatically) remodeled by chefs ever since its birth in the late 1800s. A local New York newspaper article in 1889 described an early version at the Union Club in Manhattan as “two slices of toasted Graham bread, with a layer of turkey or chicken and ham between them, served warm.” The sandwich continued to appear in newspapers and cookbooks over the next decade, including mayonnaise, bacon, lettuce, and, by the early 1900s, tomato. In 1904, the sandwich was featured by multiple American restaurants at the World’s Fair in St. Louis, as Pamela J. Vaccaro writes in Beyond the Ice Cream Cone—which was likely how it started its journey into kitchens around the world.

Riffs involving sardines, eggs, and raw beef began emerging, and by 1972, James Beard was coming down hard on what he considered to be “bastardized” versions—including touches like a third piece of bread in the center or the use of turkey instead of chicken.

“James’s understanding of a club sandwich was that it should highlight delicious cold roast chicken,” John Birdsall, author of The Man Who Ate Too Much: The Life of James Beard, tells me. Birdsall recalls a letter Beard wrote to a collaborator detailing his first picnic memory (sometime in the mid-1910s), which was highlighted by a hamper of club sandwiches made by a bakery in Portland, Oregon.

Adaptations that Beard would find sacrilegious are still everywhere in the United States—from chains like Jimmy John’s, which has eight club sandwiches on its menu (including the “Italian Night Club,” featuring salami, capicola, ham, provolone cheese, onion, oregano, and basil); to New York City’s Golden Diner’s chicken katsu club, a triple decker with red cabbage slaw and tonkatsu sauce.

“People laugh when I tell them this, but the definition of a club sandwich is that it must have the name ‘club sandwich,’” says Saunders. Saunders has reviewed clubs with lobster, fish cake, roast beef, meatloaf, seitan, and tofu, on every kind of bread imaginable. Layered in and spread on them are feta, brie, fontina, pickled ginger, cranberry-cherry relish, pear chutney, and tomato confit. One was a fruit-and-tea-flavored club sandwich cake from a hotel in Bangkok—“even though the club was quartered, it did not need a toothpick to hold it together; the green tea sponge did the trick by playing the role of the bread. The mango jelly—presumably the meat of this treasure—added a nice flavor.”

“People laugh when I tell them this, but the definition of a club sandwich is that it must have the name ‘club sandwich.’”

Though Saunders welcomes creative club sandwich interpretations, he’s committed to objective reviews, rating each on a 100-point scale incorporating value, ingredient quality, “mayo/sauce usage,” and “holdability,” among others. The highest-rated sandwich received a 94.3, and it actually looks very much like that cartoon club (it’s a turkey and ham sandwich neatly quartered into triangles, stuck with toothpicks); the lowest rating to date is 43.3, from a room-service sandwich seemingly made with stale ingredients and too much mayonnaise. Typically, there’s more room for formal critique.

A mortadella club wrap (79.5) offered at the Walt Disney Studios employee cafeteria in Burbank, California, was well priced and used decent-quality ingredients, but it was bland: “While not too visually appealing, my hopes were high that its flavors would arouse my senses in a way Disney films had done for many years,” Saunders wrote. (This restaurant isn’t open to the public, but a friend provided access to the Disney campus.)

Most hotels Saunders visits are larger accommodations with restaurants likely catering to Americans on vacation or business trips. He does think American travel has perpetuated the sandwich’s appearance outside of the United States, but he believes that chefs often develop an affinity for their own versions. “It’s become a universally accepted comfort food, while at the same time not being universally standard,” he said.

Saunders typically posts a review at least once a month; his last formal pre-pandemic review went up on March 1. But in May, he went on a “staycation” in Santa Barbara, near his home. The usual hotel amenities, including the restaurant, were closed, and he was encouraged to stay in his room. However, there was a club sandwich on the room-service menu: “It brought an awesome wave of calmness over such a turbulent moment. I’ll never forget it.”

Since May, Saunders has tried something completely new that he hasn’t yet blogged about: making club sandwiches at home. Joking that he now runs a club sandwich concept kitchen from his house, his favorite so far was a duck confit hash club with mushrooms and blueberry sauce on pumpernickel. What made this sandwich a club? Saunders stands by a formula rather than specific parameters: “produce, protein, a sauce of sorts, and a bread specifically chosen to pair with the ingredients.”

After Saunders and I spoke, I made my first club sandwich. I kept it classic: turkey, bacon, lettuce, tomato. Toast, mayo, cut diagonally. It was fine. As I crunched through the sandwich, it occurred to me that the club works best when it’s the only option. Ordered in a hotel room, too exhausted to venture out to a restaurant, eaten in bed, possibly between sips of warmish beer. Devoured in a diner with the biggest pile of French fries available, fresh from ten hours in the car. Or even on an early evening in Barcelona, knowing that dinner is hours away.

When we spoke, Saunders was preparing for a cross-country move to the Boston area. Though the main reason is to be closer to extended family, he’s perhaps just as eager to arrive in an area with new restaurants and hotels where he can get back into blogging: “I absolutely will cherish the moment that I’m in an environment like that, surrounded by new club sandwiches.”