All hail the pizza world’s latest obsession. It’s giving Americans permission to celebrate the puffy, crispy, abundantly cheesy pies some of us have loved all along.

Peter Reinhart was helping out a restaurant in Texas when the great powers of a Detroit frico crust hit him like Newton’s apple.

“We were testing all these recipes, and on the seventh day, as soon as I pulled the pan out of the oven, I knew we nailed it,” he recalls of the moment in 2017. A four-time James Beard Award–winning author who’s literally written the books on American pizza and the country’s bread revolution, Reinhart talks about flour grinds and gluten development with the high-key buzz of a kid at Chuck E. Cheese’s, and here his voice takes an upward lilt. “I got so excited. I was thinking about pan pizzas for a while, and thought if I could apply these methods to any pan pizza, I might be onto something.”

For those not attuned to the rhythms of regional pizza arcana, frico is what happens when you shellac puffy pizza dough with cheese and bake it in a well-oiled pan. The cheese bonds to the metal edge and the dough underneath, forming a crenellated border of salty burnt dairy that rises slightly above the pie, like the walls of some provincial castle ruled by Little Caesar himself. Good frico crackles audibly when you take a bite, joining a fried bottom crust in a symphony of crunch.

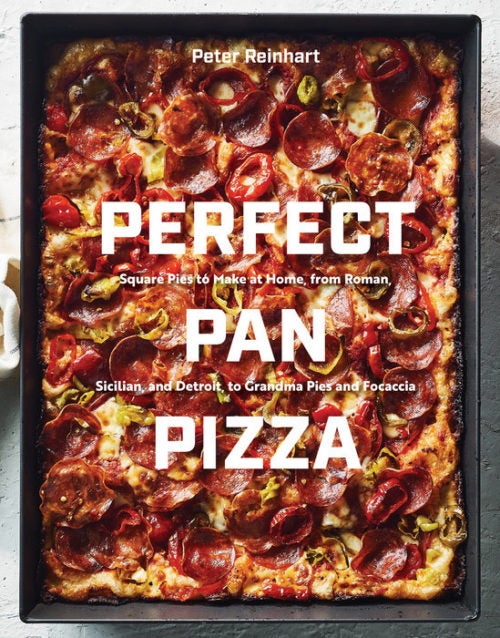

Seven months after his come-to-cheesus moment—warp 8 in the book-publishing space-time continuum—Reinhart sent a finished manuscript of Perfect Pan Pizza to his editor. The cookbook, Reinhart’s 12th, includes master dough and sauce recipes for Detroit pies, Sicilian squares, rectilinear Romans, and pizza-adjacent focaccias. It features classic toppings, such as olive and artichoke, and unconventional variations, like a Kansas City burnt-ends pie and a cioppino-inspired slice layered with ‘nduja salami. Though Reinhart wouldn’t say it himself, Perfect Pan Pizza is a convincing argument for an old chestnut bandied about in pizza circles: Italians may have invented pizza, but it’s the Americans who perfected it.

Pan-baked square pies are enjoying a moment. You can get a great Detroit slice these days in Chicago, San Francisco, Pittsburgh, and New York. Squishy Sicilians and unrepentantly oily grandmas are unavoidable on Instagram, especially those done up for the camera with orthogonally arranged up-curled pepperoni slices. The “pan” division of the International Pizza Expo’s 12th annual baking competition—the galactic senate of the pizza-making universe—has grown from a sideshow contest to a fight nearly as fierce as the Neapolitan and American categories, Reinhart explains. (He would know; he’s attended half a dozen pizza trade shows across the country and judged this and similar competitions three times.) When he pitched the idea of a pan pizza book to his publisher, “my editor said don’t even waste time on a proposal. It was so on trend they didn’t want to wait.”

Reinhart considers it a natural product of the pizza world’s maturation and our growing hunger for new kinds of pie. “Over the last 15 years, the methodologies of the artisan bread movement have been getting applied to pizza,” he says. “The quality of crusts has gotten much better in that time, and the crust is what’ll drive you to obsession. People are developing skills in these [pan] styles that show they can be just as satisfying as Neapolitan.”

Neapolitan pizza aesthetics—airy, leopard-spotted crusts, nearly soggy centers, and pristine Italian ingredients—is a particularly demanding art form. But making good pan pizza comes with its own challenges. You can’t nail that frico with any dough and pan, and even after you’ve found a crust you’re happy with, you could spend a lifetime tweaking the acidity, sweetness, and spice of your sauce.

Adam Kuban, the founder of the pizza blog Slice and showrunner of a bar-pie pop-up called Margot’s in New York, describes Reinhart’s 2003 book American Pie, a narrative quest across the country in search of pizza enlightenment (with recipes), as a seminal text in those early days. “It was a huge resource,” he says, adding that the book, and pizzamaking.com, a website that also launched in 2003, quickly became the discussion board for pizza obsessives. “[Specialty pizza] wasn’t mainstream then; if you wanted to improve your pizza game, that [book] was pretty much it.”

Kuban is one of a handful of pizzamaking.com regulars who turned his pizza obsession into a professional operation. Before he opened Varasano’s in Atlanta, Jeff Varasano was “the original viral pizza geek” on the site, as Kuban puts it. Scott Riebling of Stoked in Boston, Peter Taylor of Wood Fired in Tampa, Norma Knepp of Norma’s in Lancaster, Pennsylvania—all forum members who have since opened celebrated pizza spots despite having little to no prior restaurant industry experience.

Knepp, a 72-year-old retiree who previously worked at an energy company, says she built out a pizza stand at Roots Country Market in 2009 using some equipment abandoned by another vendor. She took up the pizza peel in part to pay her husband’s medical bills, turning to the forum for advice since she didn’t have a clue how to make great pizza and local experts could only offer limited advice. “I would have never understood pizza by myself,” she says. “Even if you do everything in a recipe the same, your dough will turn out differently each time. There’s so many members on [that forum] that’ll suggest different approaches to help you out.”

Kuban describes Knepp as “kind of a legend” in the pizza community, a tinkerer with a knack for analyzing and replicating legendary pies. She achieved national fame in 2016 when she won the USA Caputo Cup in the “New York style” category, and she currently sells New Yorkish slices and Sicilian squares baked in deep Detroit-style pans.

It’s not surprising that after a decade of doggedly pursuing Neapolitan and New Yorkish pizza perfection, America’s pizza nuts have moved on to something new. But pan pizza’s ascendancy is still a far cry from a national discourse that’s always prioritized round over square and once revered lean wood-fired pies as the pinnacle of pizza achievement.

When I was an editor at a pizza-obsessed food website in the early 2010s, every day seemed to bring a new upscale pizza restaurant with thin-crust leanings and an over-reliance on speck and burrata. If it wasn’t a new-school pizza joint, it was a story about some obsessive who’d hacked their home oven to reach the searing 800 degrees required for those lightning-cooked Italian pies, or debates over flours and fermentation times for optimal no-knead dough.

When the press covered these openings and innovations, the unspoken subtext was often that they stood as elite contrasts to the unfashionable, mass-market hallmarks of the American pizza experience: tasteless doughs, meat lovers’ toppings, cheese-stuffed-crust gimmicks, cinnamon-sprinkled breadsticks to dunk in cream cheese frosting. Here come the urbane disruptors to save American pizza from its terminal excesses.

No doubt the average American pizza has room for improvement. But you could argue that this new wave of regional pan pies has more in common with our collective Domino’s and Pizza Hut lineage than anything that’s come before them. What is an Americanized Sicilian slice if not a celebration of pillowy dough, similar in shape and heft to Michigan-born Little Caesar’s pan pizza? Maybe a Detroit frico crust is the apotheosis of Domino’s endless pursuit to maximize the cheesy potential of every bite.

But good pan pizzas are never just heavy, and they certainly follow a philosophy of abundance where Neapolitan tradition employs minimalist doughs and spare amounts of toppings. Pan pizzas demand more dough and cheese, plus oil to fry the bottom crust. There’s something compellingly American about pan pizzas’ abundance. They’re also egalitarian; unlike Neapolitan and New York styles, they don’t require maxing out your oven to surface-of-the-sun temperatures to bake successfully—around 350 degrees for 30 minutes—so they’re easy to reproduce at home. And like American identities, pan pizza styles are legion; hyper-regional square pies abound across the country.

“There’s this focus now on regional American pizzas,” Kuban says, “and a lot of them are cooked in pans. So everybody is trying to do a celebrated square.” An airy, baroque dough, a crunchy crust, a cozy quilt of cheese—a pizza we’ve loved all along.