In the mid-aughts, NASCAR was everywhere. And so, for better or worse, were NASCAR-inspired cookbooks.

Blame it on a national need for speed, or the country’s post-9/11 appetite for nuggets of Americana à la Lee Greenwood’s patriotic smash “God Bless the U.S.A.,” but in the mid-2000s, you couldn’t toss a lug-nut without hitting some form of NASCAR-adjacent media.

There was the Speed Channel, which was dedicated to 24 solid hours of NASCAR-related programming. There were NASCAR video games and NASCAR Illustrated and NASCAR Speedparks—essentially, branded go-kart tracks—that cropped up from Myrtle Beach to Missouri. And then there was, of course, Talladega Nights, the 2006 Will Ferrell, ahem, vehicle that had racing fans everywhere proclaiming, “We go together like cocaine and waffles!”

In the era when Larry the Cable Guy was selling out arenas, a pastime once regarded as catering strictly to a rural, predominantly white, mostly conservative audience found an undeniable, if curious, national appeal. By 2006, NASCAR boasted a projected fanbase of 75 million, and the Daytona 500 saw its largest crowd ever, attracting 20 million viewers. Shortly thereafter, Forbes coronated NASCAR as “the fastest-growing sport in America.” And with a NASCAR poster on every wall, it was time for the organization to help put a NASCAR-branded chicken in every pot—in the form of racing-themed cookbooks.

Cookbooks were a staple of local car-racing culture long before the mid-aughts NASCAR boom. Typically self-published, they were compiled by the community as both fund-raising tools and end-of-season tributes, and designed to be shared with friends, neighbors, and fellow racing fans. The books, which were often spiral- or comb-bound, are similar in format and tone to church or auxiliary-league recipe collections. Recipes tend to rely less on instructional details and more on their contributors’ enthusiasm. (The Phoenix International Raceway Tailgate Cookbook’s recipe for “Hot Honey-Lube 500 Ribs” screams that you “MUST USE DR. PEPPER!” when making the ribs, then “MUST EAT WITH A COLD BUD BEER!”)

John Youk, the author of Big John’s Speedway Grill

During the 1980s, the NASCAR Racing Wives Auxiliary—a race-day-adjacent nonprofit—produced the most notable series of cookbooks, using the annual collections to raise funds for injured or killed drivers and their families. Given NASCAR’s still relatively small commercial footprint, they retained many of the stylistic features of the homegrown cookbooks, with testimonials from husbands about their favorite post-race dishes and recipes laid out like homespun recipe cards.

But by the turn of the 21st century, NASCAR had burned enough rubber (and raked in enough cash) to sear its identity into the public consciousness. Soon outlets from NPR to The New York Times were clamoring to write about the entire NASCAR culinary ecosystem, from prerace tailgating dishes to what, exactly, these wannabe-celebrity drivers snacked on to fuel up.

“If you don’t consider turning left for three hours a real sport, you might wonder what nutritional perspective a NASCAR driver’s diet might offer,” Kim Severson wrote in a 2006 New York Times story about NASCAR’s attempt to shake off its fried-food-and-Moonpie image as the sport veered toward the mainstream. “But proper food and hydration is becoming as important on the racetrack as it is on the football field or the tennis court.”

The shift toward sushi and skinless chicken breasts among drivers created a sort of culinary identity crisis for longtime racing fans who were used to seeing their favorite athletes house chili dogs and potato salad. Homespun recipe collections with dishes like “Big Daddy’s Hearty Hound Dog Clam Chowder” and “Fuel ‘n Go Baked Beans” were being outshined by slick, nationally marketed, NASCAR-produced cookbooks that detailed a race day menu more befitting an owner’s suite than the tailgating infield.

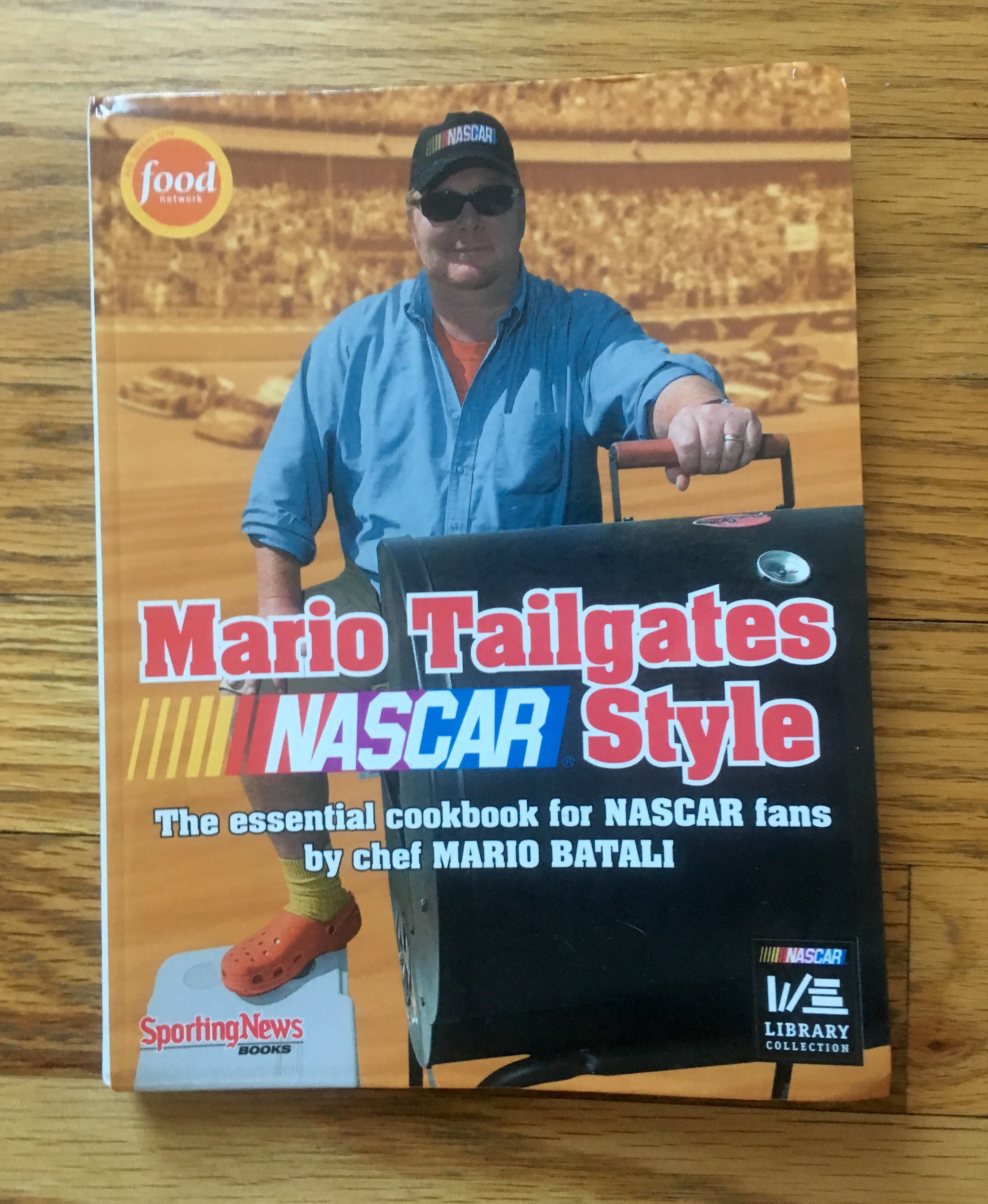

Mario Batali’s puzzling foray into the world of NASCAR cookbooks

“The biggest reason that these cookbooks became a big deal at the time is that NASCAR, as a sport, was really at its height. Also, the demographics were shifting, with more women and younger people getting into it,” recalls Angie Skinner, wife of former NASCAR driver Mike Skinner and the author of Race Day Grub, a 2007 cookbook that speaks to racing culture cuisine with dishes that have actually been prepared trackside. “It’s also when the Food Network was taking off, and I know it…inspired me to do more creative things, like a taco bar, when we’d invite [my husband’s] team over to the motor coach after days of practice. It wasn’t just burgers and brats anymore.”

The glut of cookbooks representing the “new” NASCAR included recipes that, at best, recalled the Auxiliary cookbooks and, at worst, were deeply questionable. In NASCAR Cooks With Tabasco Brand Pepper Sauce, published in a cobranding effort with the company, a whole host of oddball dishes are laid out, with each one loosely attached to a driver’s persona. There’s Sterling Marlin’s Tuscan Summer Salad, complete with hunks of Italian bread, arugula, and capers, and even stranger, Jimmy Spencer’s Curried Carrots and Raisins. (Try pulling a Tupperware full of that out in the middle of a packed, sweat-drenched grandstand.)

Then there’s Big John’s Speedway Grill, written by the self-proclaimed “Grill Master to NASCAR Drivers” Big John Youk. While its recipes are more in line with traditional racing fare, the titles are so burdened by stereotype (Double Wide Baked Potatoes, Banjo Pickin’ Rubbed Chicken) or bizarre innuendo (Not Commie Red Beans and Rice) that it’s hard to even make it to the ingredient list.

Batali also suggests making negronis to keep on hand while tailgating, referencing—bizarrely—Salvador Dalí and Luis Buñuel in his explanation.

But there was no greater ham-fisted attempt to cash in on NASCAR’s popularity bubble than Mario Batali’s 2006 cookbook, Mario Tailgates NASCAR Style. The book—which Batali erroneously (and smugly) claimed was “the first ever cookbook for NASCAR fans”—was reportedly born of an attempt to broaden the chef’s fan base while “elevating” NASCAR’s reputation.

Mario Tailgates has a roster of scattershot recipes that seem largely impractical for the track, both logistically and spiritually. Dishes like “Cuban-style chicken thighs with grapefruit mojo” require multiple phases of prep work. Bananas foster is recommended as a trackside dessert, without any regard for the fact that lighting rum on fire in a crowded tailgating setting could be, you know, a fire hazard. Batali also suggests making negronis to keep on hand while tailgating, referencing—bizarrely—Salvador Dalí and Luis Buñuel in his explanation rather than anything even remotely related to NASCAR.

While the book sold relatively well at the time, Batali failed to understand that racing cookbooks aren’t the kind of tomes bought as status symbols, or for the photography, or to be used once before being repurposed as doorstops. They’re for extensive, grease-stained, down-in-the-trenches use, the kind of books that get referenced, passed around, and tattered instead of being admired from afar.

It’s often hard to imagine who exactly the audience is for most of the mid-aughts NASCAR cookbooks—if there even is one. That might be a reason why they, like the Speed Channel, were left in the dust long ago. In my quest for copies, I came away empty-handed, even at specialty bookstores; I patched together a collection thanks to eBay and, yes, garage sales. As interest in NASCAR has plummeted over the past decade (down 45 percent since its peak in 2006), the peripheral promotional items have flamed out of the public consciousness as quickly as they raced in.

But the disappearance of NASCAR cookbooks may not be a loss at all. At the end of the day, longtime NASCAR fans know that you don’t need braciola or berries with zabaglione (two of Batali’s suggestions—really, this is real) to properly enjoy the chaotic, rainbow blur of cars whizzing around the track and the metallic grunts of the pit crew’s pressure gauges and fire-spewing welders. Most would prefer to mix their race-day enthusiasm with a cold beer and a hot dog right off the roller—no recipe required.