The spicy, acidic curry tells a complicated, labor-intensive story of colonial rule and national (and personal) identity.

Sorpotel is not an everyday dish. The bracingly acidic Goan curry of pork offal punctures big occasions and announces sacraments: weddings, christenings, and first holy communions, as well as Christmas and Easter. In the old country, the initial step for a dish so momentous was a brutal one: “First, kill a pig.”

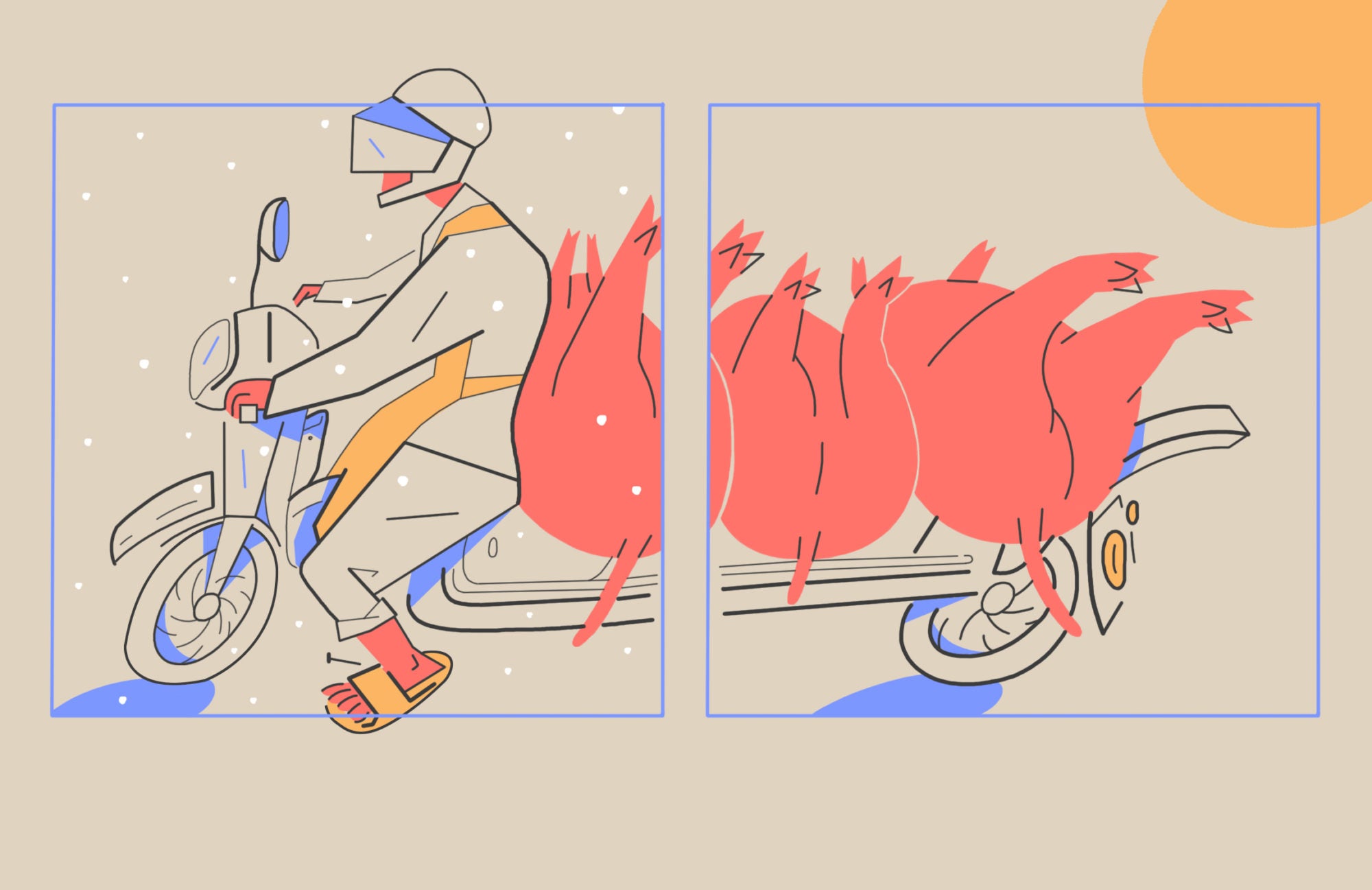

The last days of a Goan pig’s life are ignominious: Beadily watched until girthy enough around the belly, it is then slung upside-down on a motorbike, tail tied to snout, to be taken to the butcher. When a pig was slaughtered in the old days, women would catch the blood in a bowl, not simply for cleanliness but to later thicken the complex stew. No part of the animal would go to waste—buckets of bloody viscera would be cleaned and sorted, and what meat wasn’t used for sour, rosary-bead-like Goa sausage could be saved for sorpotel. This was “nose to tail” long before Fergus Henderson got to it—a fact of life rather than a manifesto.

While many Goans now make sorpotel only with pork, I’ve tasted versions with liver, tripe, intestines, kidneys, and pig’s ear (albeit not all at the same time), all of which add their own unique funk and texture. Most Goans now make sorpotel without the blood, and some even without the offal. Savio Azaredo, the owner of Olde Goa, a Goan restaurant in south London, makes his without the liver for the benefit of his non-Goan clientele, but he’ll still prepare some with liver on request for members of the Goan diaspora who miss it. He makes it from scratch every Monday, when the restaurant is closed, using hard-to-source toddy vinegar, feni (cashew liquor), and jaggery imported from Goa. “This is soul food,” he says. “You can’t cheat on ingredients.”

My mother, who like many Goans was brought up in Kenya and came over to London in the ’70s, has an early memory of her own mother in Mombasa returning from the market, arms comically full of whole pig’s heads, to scrape out the fatty head meat and dice cartilaginous ears to make sorpotel for a wedding. My grandmother was by all accounts a phenomenal cook, but it was a role forced onto her, trapped as she was within the confines of Indian patriarchy. As a young girl, she’d been sent from Tanzania to live with her uncle in Goa in order to gain an education. But on her return, her father was livid to discover that she had instead been put to work in the kitchen, making laborious dishes like sorpotel in the early hours of the morning. To this day I have never tasted a home-cooked sorpotel made by a man’s hand. It is a dish built on the blood and toil of women.

It is also a dish that reflects the particularity of the Goan identity and the centuries of colonial rule that shaped it. Ask a Goan where they are from and they will say Goa, and then lengthily explain where Goa is rather than simply saying India. Similarly, try to find any dish that resembles sorpotel among India’s myriad cuisines and you will come up short. The reasons for this are bound up with the history of Goa, which was first passed around casually between various sultanates and dynasties before becoming the jewel in the crown of Portuguese colonial India in the early 1500s.

The Portuguese found it hard to relinquish Goa, hanging onto it for over 450 years until even the British thought they should hand it back. It wasn’t until 1961, 14 years after partition, that India, now impatient, invaded Goa and annexed it, turning it into one of the last puzzle pieces in the creation of the modern Indian state. What the Portuguese never relinquished was an influence on Goa’s culture, particularly its food. Along with Catholicism, they brought a love of pork and wine vinegar to remind them of home. The Goans adapted the latter into their own coconut vinegar, made by fermenting toddy, or the sap from palm tree flowers. The vinegar is vital to sorpotel, not just for its taste but also for prolonging its life, improving it each day it marinates.

Just as crucially, Portugal imported culinary influences from its other colonies: chiles from South America to add spice to curries; cashews from the New World to make feni, Goa’s beloved moonshine; and cooking techniques from Brazil and Mozambique. In her essay “Mapping the Cultural Geography of Goan Gastronomy,” the academic Supriya Roychoudhury challenges the narrative of Portuguese dominance, focusing instead on the overlooked role its colonies had on the diversity of Goan cuisine. According to Roychoudhury:

“The Goan dish popularly known as cafreal chicken—grilled chicken marinated in coriander, chiles, cinnamon, garlic, and lime juice—is believed to have its roots in the Mozambican galinha piri-piri. Similarly, sorpotel, a popular Goan pork curry, is said to have evolved from the sarapatel dish devised by the African slave community in Brazil.”

For me, my identity as a mixed-race Goan was strongest when I was eating sorpotel at family gatherings held at anonymous church halls across north London. As a child, I would always get served first and then run to the back of the queue to get seconds, and eventually third and fourths.

Now these celebratory functions are rare occasions, replaced by funerals of distant relatives I never knew I had. This shift has brought with it a new, morbid association: For every family member in a casket, another tupperware of sorpotel would wing its way to me, smuggled out by my mum for a hungry son who had no qualms about feasting on the spoils of the dead.

Regardless of the occasion, eating sorpotel has historically been a way to other myself not only from the white British culture surrounding me, but also other Indians. They knew nothing about the dish, just as I had no grasp of their cuisines. It is this difference between sorpotel and anything else in the Indian canon—the same difference between the Catholic church I attended and the mosques and temples of my Indian friends—that also became a barrier against feelings of pan-Indian identity. To employ a Cartesian variation, I eat sorpotel, therefore I am Goan.

This January, I made sorpotel with my mother for the first time. She had avoided cooking it when I was growing up; she remembered too vividly how my grandmother would labor to make it, how the pork fat would pop and the oil would burn her arms when she was forced to help out. As I expected, I was soundly berated from the moment I started, from my sourcing of meat (too fatty) to my cutting technique (generally poor) and all the other things my grandma built up through muscle memory that I will most likely never have. We cooked from my mother’s notes, taken when she was a young woman watching her mother, but as always, you cannot replicate intuition.

We eventually made three kilos in one of those bottomless pans that every immigrant mother has. I took a kilo back home to marinate in the fridge, and the rest was distributed to friends and family. A week later my mother phoned with a story that unexpectedly moved me. A friend of hers from Kenya was now in a London hospital, being treated with chemotherapy, and his wife had asked my mother to bring him some of the sorpotel we made. Chemotherapy messes up your sense of taste, and he wanted something strong to reset it. He recalled eating my grandmother’s sorpotel when she sold it from her home in Mombasa, and his memory of it was still sharp.

To me, the thought was almost overwhelming: to have been a part of this thread, making sorpotel under the direction of my mother, using the recipe of my grandmother, to re-create an almost 50-year-old memory of diasporic longing in East Africa for home across the Indian Ocean. It was a confirmation that wherever we are, sorpotel is in our blood.