There’s an analog, and spiritual, approach to making one of the world’s finest cheeses—one you may just take for granted.

In Emilia-Romagna, the most exhilarating scenes play out in rooms where nothing happens.

Teardrop-shaped boneless hams freed from a hog’s hind leg, culatello di Zibello dangle for months in cellars made musty by heavy mists peeling off the river Po. Balsamic vinegar makers in Modena let grape juice go for decades in barrels generations older than their own children. In this agricolo enclave, the back of the knee upon Italy’s boot, waiting for what seems like forever is not a chore. It’s the only way to work.

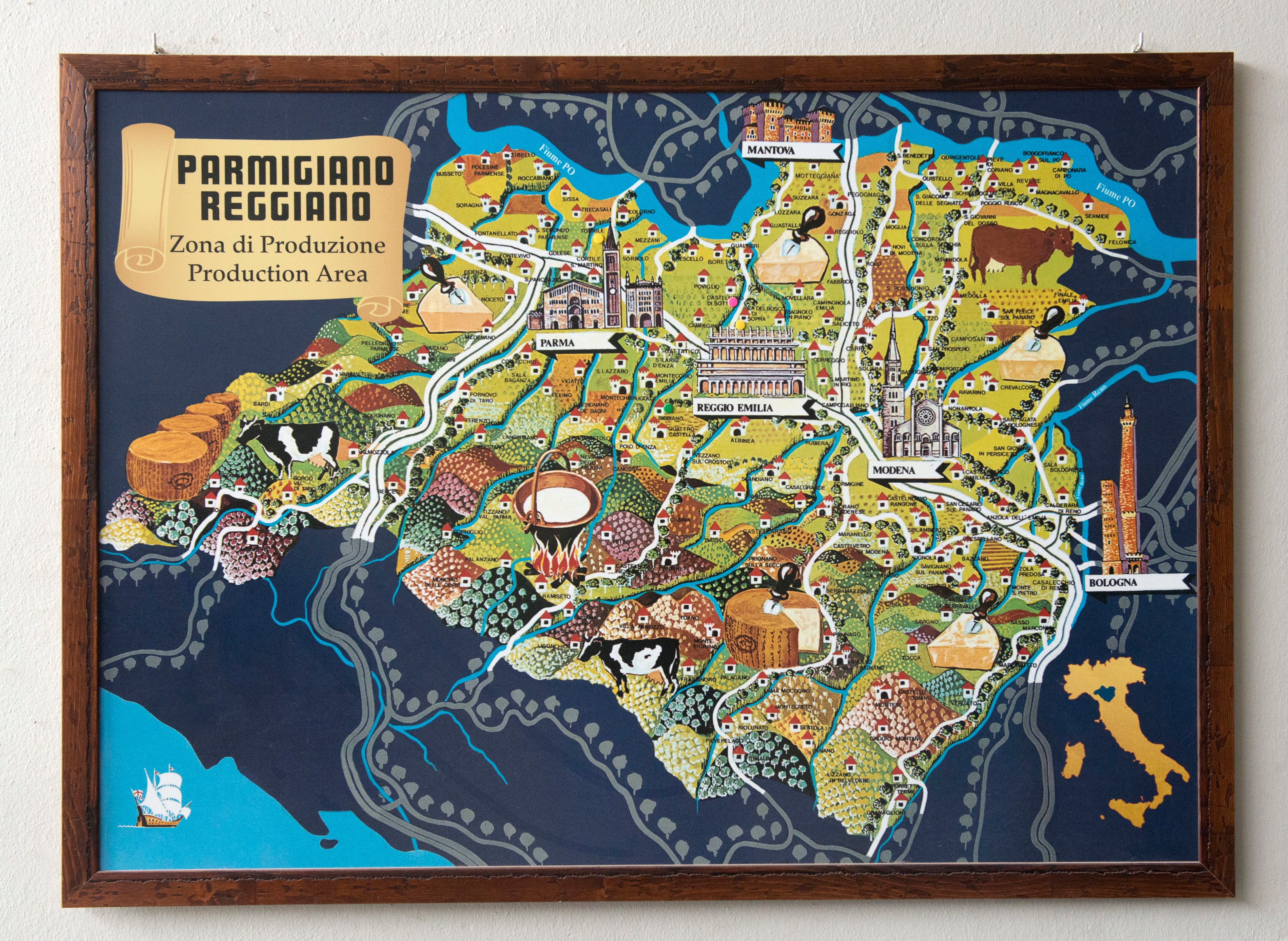

Long-term investments of patience always pay out up here, a northerly region about the size of New Jersey with the urban-rural mix to match—big cities like Bologna and Modena share acreage with medieval villages, planted fields, and lolling hills. Since we, as eaters, come in at the tasting end of the transaction, it’s hard to grasp what time spent actually looks, sounds, smells, and feels like.

Stepping inside the door of the pin-drop-silent aging warehouse of Latteria La Grande and glancing up once helps me get it. Intimidating in scope, with soaring hangar ceilings studded with industrial lights, this is a space awe-inducing enough to host a 40-vehicle Fast and Furious action sequence. But instead of beautiful people crashing beautiful cars, I see, and sniff, something better—thousands of toasted-gold wheels of Parmigiano-Reggiano, the cash cow not-so-humbly crowned the “King of Cheeses.”

As I strain my neck in a weak attempt to take it all in, Anne Meglioli narrates. “Here,” she says, “we are not doing anything.”

One of the 299 Italian sites legally permitted to make Parmigiano-Reggiano (all fall within a roughly 50-mile radius), La Grande, in the commune of Castelnovo di Sotto, is among the busier facilities of its ilk in terms of output: 18,000 wheels on an annual basis. Bucolic as the surroundings may be, the creamery went a little Epcot in engineering its main entrance—a two-story-tall Parm round stood up on its skinny side, the front door recessed within a triangular wedge along the bottom.

Meglioli, a French woman who married into the E-R way, is a decorated food expert who makes her living educating people like me on the antiquated alchemy that transforms 550 liters of raw milk into a single wheel of the salty, savory, uncompromising hard cheese waiters so eagerly shave on our spaghetti. Before reaching this resting place, stacked to the sky some 36 feet high on wooden shelves alongside an army of seemingly identical siblings, Parmigiano-Reggiano starts outside.

The process begins with prized Frisona dairy cows that are fed a meticulous local diet of hay and/or protein-rich grains dictated by the governing Consorzio Parmigiano-Reggiano. These animals are milked daily, at specific hours: “night milk,” with its buttercream skimmed, is mixed with the full-fat “day milk” collected each morning, and this combo is key to cultivating the cheese’s singular flavor and texture.

This unpasteurized mix, an alluring off-white the color of cotton, is treated with veal rennet and fermented whey, then heated up fast in open copper cauldrons, a cinematic process that casts off thick fingers of Macbethian steam. Dressed in baggy work unis and rubber boots the same hue as the dairy they’re manipulating, La Grande’s cheesemakers break apart the quick-forming curd with an unwieldy pole whisk known as a spino. I witness one particularly stoic man plunge his unarmored hand straight into the roiling kettle to check on consistency—fine pebbles, at this level—without flinching a millimeter.

“He is not human,” Meglioli, seeing me seeing him, reassures. It’s a cheeky way to compliment an artisan’s cyborg-like scald threshold, but in practice, this precise skin-to-product connection is what the Consorzio values most. Slowly, surely, the sand-like granules of curd come together into a smooth-textured ball he sculpts by hand and slices in half, coaxing a pair of proto-wheels to life inside linen hammocks suspended from a metal pole balancing across the mouth of the cauldron.

Aside from the slightly updated equipment, it’s not a dramatic departure from how the Benedictines did it in the Middle Ages. “Here is an important moment, because it is the human that is deciding when to cut the curd,” Meglioli says of this hushed but significant step. “All the moments that bring it from one stage to another are decided by man.”

The analog approach continues through the shaping, when the curd halves are fit into hard plastic molds and painstakingly squeezed with a draconian block-and-rope tool that looks better suited for flogging than formaggio. This expels residual whey from the hard cheese in preparation for its tattoos, a battery of QR Code stamps and dot-matrix rind indentations that indicate birthdate and source dairy—marks proving this Parmigiano-Reggiano is really, really real. But the cheese still can’t be called by that name until after it’s been brined, bobbing for 20 days in a sea-salt solution, then aged for anywhere from one to three years in La Grande’s cavernous maturation vault.

Back in this serene, somewhat eerie room, cheese new and old truly does just sit there. La Grande’s maximum capacity is 23,000 wheels, every one of them deepening in color and sharpness and pungency with each passing day. Every so often, the wheels are flipped and gently brushed to shoo away unwanted molds and films. The Consorzio actually looks to automation for this step, relying on a multitasking machine that Meglioli can’t help but anthropomorphize. “She is a lady because she does many things at the same time,” she says. “She’s a little noisy, but it’s OK. She’s not perfect.”

Troubleshooting is hands-on. The slightest wrinkle or dent can translate to problems down the line. Potential disasters are handled by specialists trained to literally bang on wheels with hammers and flag potential issues with their ears—percussive cheese diagnosticians. They’ll also perform emergency “surgery” to neutralize small flaws before they get bigger. Not every wheel is destined for the coveted Parmigiano-Reggiano designation, either. In Italy, specimens that fail to meet the Consorzio’s strict standards are wiped of markings and reclassified as sbiancato, or “white cheese.” Wheels with only slight defects earn the “Mezzano” label and are sold at cheaper prices—still Parmigiano in spirit, but not fit for the crown.

In America, however, there are no laws of provenance prohibiting companies from hawking far less fussed-over cheeses labeled, simply, “Parmesan”—the powdery, clumpy stuff in green plastic cylinders we grew up scattering over our Spaghetti-O’s. That’s to say nothing of products that fudge designations, or outright lie on labeling; Meglioli estimates some 80 percent of so-called Parmigiano outside the Italian market is of dubious origin. To know it’s legit, examine the rind—and, more obviously, be willing to pay a higher premium.

Though Parmigiano-Reggiano shares Emilia-Romagna with plenty of other DOP dairy heavies—Parm people and Grana Padano people seem to harbor a intra-regional rivalry—the King of Cheese stays the King of Cheese throughout Europe, despite harsh licks, like the 2012 earthquake that affected some 770,000 resting wheels, translating to multimillion-dollar losses for the industry.

While they stand their ground at home, the Consorzio’s aim for America is far broader: trying to convince everyday cheeseheads here that Parmigiano-Reggiano has greater applications, beyond the grater. In France, “a piece of cheese is compulsory to every meal,” says Meglioli, showing her Parisian roots. “While in Italian cooking, cheese is often an ingredient.” In the States, meanwhile, “Parm” is largely considered a condiment—an inexpensive one.

Visiting La Grande left me with the grand idea that people might start making distinctions if they knew how much labor went into even the smallest sliver of authentic Parmigiano-Reggiano. But I also know it’s presumptuous to assume that everyone thinks the hard way is the better way, in terms of cheese or otherwise. We’ve topped a few too many frozen pizzas over the years for our perceptions to change posthaste. Good thing Italians don’t mind waiting.