Since the ’30s, icebox cookies have given busy working people a chance to slice, bake, and serve dessert at a moment’s notice.

In 1931, Irma Rombauer spent half her savings to print a collection of family recipes. She called it Joy of Cooking. The book coincided with two important moments in American history: Refrigerators were starting to make their way into more and more homes, and women increasingly started leaving the home to enter the workforce. The book, filled with practical, do-ahead recipes that wouldn’t cut too much into a home cook’s busy workday, became an instant classic.

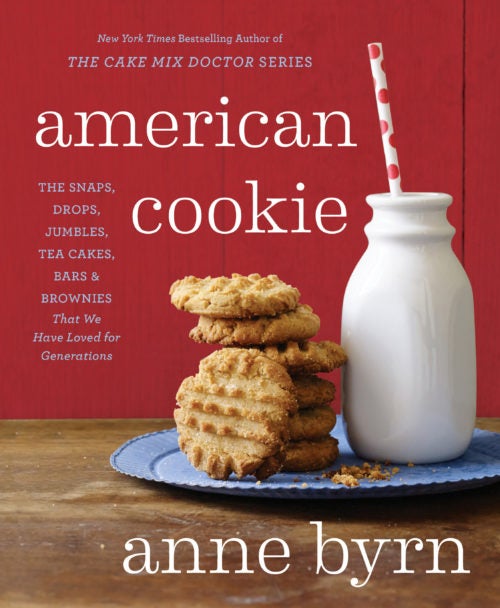

While writing my book American Cake, and more recently American Cookie, I was struck by how Depression-era cooks embraced this plan-ahead attitude while creatively using refrigeration. In the 1930s, women entered public school cafeterias as lunch ladies. They opened tea rooms. They became nurses and teachers. And to help these cooks with work-home balance, as well as the rationing tickets that would arrive with World War II, cookbook authors and newspaper food columnists stressed low-cost, quick-fix recipes that would boost the family’s morale. Out of this movement arrived the icebox cookie.

Named after the refrigerator’s predecessor (the icebox), these were cookies you could keep refrigerated, then bake at a moment’s notice—essentially a 1930s version of a Pillsbury slice-and-bake cookie. Home cooks could make the cookie dough before they went to work, roll it in sheets of waxed paper or store it in leftover milk cartons, and place it in the refrigerator until they were home and able to bake. With dough in the icebox, you were ready for friends and family to come calling—or a visit from the local preacher on a Sunday afternoon. Having a quantity of homemade food at the ready was both a welcoming gesture and a source of social capital.

Today, icebox cookies are practical for the same reasons they were during the Depression. They can be made with whatever mix-ins you have on hand, whether it is chopped dates, coconut, or pecans. They can contain brown sugar, cane syrup, or even corn syrup (harkening back to when the prices of white sugar soared too high), sometimes with dates or raisins for a little added sweetness. They can be made with a heavy portion of oats (and low on flour, which was helpful when people were faced with wartime flour rations), resulting in a thin, flat cookie with a lacy texture.

You can make a tiny bit of chocolate stretch across a whole batch of cookies by making German pinwheel cookies. This involves taking half of your sugar cookie dough and adding melted chocolate to it. The chocolate dough is laid on top of the vanilla dough and rolled into a log, wrapped in waxed paper, and chilled. When sliced and baked, these cookies form a beautiful spiral from the two contrasting doughs.

Because pinwheels, along with other icebox cookies, welcome substitutions, you have carte blanche to create your own version. Mix some grated lemon zest, chopped lavender, benne seeds, coffee, or pistachios into the interior dough. Use olive oil instead of butter. The dough actually improves while it rests in the refrigerator as the flour soaks up the liquid and creates a more even-textured cookie, so don’t be afraid to make them a few days ahead of your guests.