It’s rashers and local tubers for days for an American expat living in Ireland’s Wild West.

I had promised our new Irish friends some real barbecue, the way we do it back home in Texas. So I bought some nice-looking racks of baby back ribs at the local supermarket, threw them on the Weber, and slow-cooked them over Irish hardwood lump charcoal and ash wood until they were just right, then served them up with some of my homemade barbecue sauce (the secret recipe starts with garlic butter). The result? A comic spit-take into my napkin after my first bite of salty, dried-out pork shards. Inedible.

A longtime American expat at the dinner table consoled me while explaining where I went wrong—I had mistaken Irish bacon ribs for baby backs. Bacon ribs are treated with the same salty cure used for American bacon. Nice for braising with cabbage, but for barbecue, they are rubbish, as they say over here.

Instead of spreading the gospel of barbecue and Tex-Mex, I discovered that I first needed remedial cooking lessons. Though I’ve written a pile of cookbooks, I felt like I was starting over.

My Irish food adventures began last January when my wife enrolled in the studio art PhD program at the Burren College of Art in rural Ballyvaughan on the south shore of Galway Bay. When we arrived, we rented a house not far from the school on Ireland’s rural west coast. While she’s in her studio and our kids are in school, I spend my time combing the countryside for groceries.

From my kitchen window, I watch a lobster boat pulling out from the dock every morning. I have foraged in the intertidal flats for pepper dillisk, an amazing seaweed that tastes like truffles; cut delicate rock samphire on the beach; dug for meaty razor clams in the sandy bottoms; collected tiny periwinkles; and even sampled a few limpets (very chewy). I can buy blue lobsters, brown crabs, local oysters, clams, mussels, and fresh fish at the seafood store beside the New Quay boat dock a few miles from my house.

Carrots, parsnips, new potatoes, and leeks are available from a local farmer named Annie. She has a stall at the farmers’ market in nearby Kinvara, or you can stop by her farm in New Quay and knock on the door. The Irish like their root vegetables with some dirt on them to prove they are fresh. Once you scrub the mud away and cut them up, the carrots have a bright, floral sort of aroma—they are much crisper than any I’ve had in the States. I’m just learning about parsnips. I have used them in chicken soup, but in Ireland they’re very sweet and most commonly roasted in butter.

The Irish have a complex relationship with the potato. The Potato Famine of the mid-1800s shaped the country’s history, but it didn’t extinguish the Irish enthusiasm for spuds. Diners here think nothing of ordering a spicy Indian curry with chips (as French fries are known) at an Indian restaurant. The most popular meal at our local pizza joint is an order of cheese fries and a pizza. (You eat the chips while you wait for the pie.)

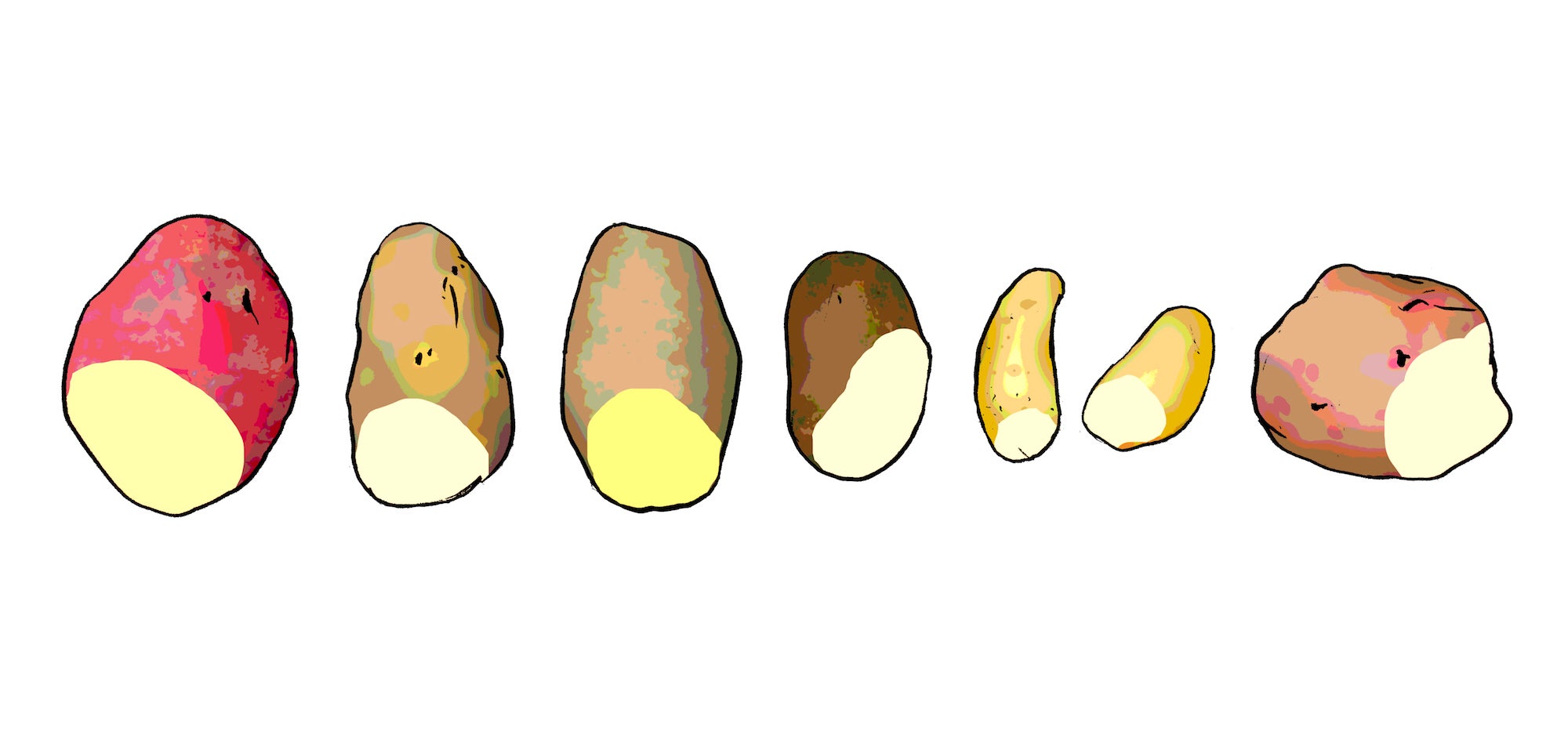

There is a potato for every purpose—six main varieties are sold in Irish supermarkets, along with another half dozen heritage types. I am slowly learning the nuances. Boiled new potatoes are a delicacy; they are served in simple potato salads. Queen potatoes make great crunchy “crisps”(potato chips) but get tough and woody when roasted. I like waxy “Italian” potatoes for American-style potato salad with mustard and hard-boiled eggs. The Irish potato board recommends the type called Roosters for mashing and just about everything else. The best thing about this large, red-skinned variety is you don’t have to peel them, the lady at the cash register confided.

The first time I tried to boil Rooster potatoes, I ended up with a pot full of tiny potato fragments. What did I do wrong? I asked Paddy the potato vendor at the Galway market—he told me to put them in boiling water, then turn the heat down and simmer them gently. The Irish potato board says to put the potatoes in cold water and allow them to heat slowly while the water comes to a boil. Either technique works better than cooking spuds at a full boil, I discovered.

The cabbage behaves differently, too. There are white, green, and red cabbage heads available in the spring and summer. But York cabbage is the most common, and it’s available year round. This conical cabbage makes great braised dishes and (as I unfortunately discovered) horrible coleslaw—the loose, floppy leaves turn brown when you chop them up raw.

The Irish prefer the York variety for bacon and cabbage, the unofficial national dish. The “bacon” is actually a thick slice of gammon, a cured pork cut. I am guessing this homey Irish supper inspired the corned beef and cabbage we eat on St. Patrick’s Day. When they are roasted with cabbage, the cured gammon steaks look a lot like corned beef, but they taste like ham, only not as dry. I’ve never seen corned beef here, but the Irish sure eat a lot of cured pork.

The Irish cure nearly every part of the pig and call it all bacon. Rashers, which are cut from cured pork loin, are the standard breakfast fare. They come thick-sliced or thin-sliced, with or without rind, and might remind you of Canadian bacon with more fatty bits. American-style bacon, which is cut from pork belly, is called “streaky bacon” here. And alongside the rashers and streaky bacon there are gammon roasts, bacon ribs, and back bacon. What a great place to live if you like bacon!

The Irish are very proud of their grass-fed beef, and it’s much in demand all over Europe. Irish butcher cases feature tenderloin, striploin, and rib eye steaks as well as eye of round roasts. I once asked an Irish butcher where I could find brisket, flank, flat-iron steak, beef ribs, and other cuts. “Right here,” he replied with a sly smile, pointing at a mound of beef mince, as ground beef is known here. So now instead of the briskets and beef ribs I barbecued back in Texas, I am cooking rib eye roasts and whole tenderloins—and the results are spectacular.

While the grass-fed sirloin is pretty chewy, Irish grass-fed tenderloins are just the right texture, tender but not at all mushy. Yes, they are expensive. But the truth is, the Creekstone Farms All-Natural USDA Prime briskets Aaron Franklin recommends aren’t that much cheaper than Irish tenderloin.

But the star of the Irish butcher case is lamb. At the top end, there’s Connemara mountain lamb, a smallish black-faced breed so unique it has its own European Union PGI (Protected Geographical Indication). The meat is lean, but the flavor is bold and rich. It’s only available for a few months in the autumn. In the spring, farmers in the town where I live sell lamb by the box if you want to stock the freezer at bargain prices. The local supermarkets and butcher stalls sell lamb cuts all year round.

“Lamb mince” is my big discovery. It has a better texture than the often gristly beef mince. Irish ground lamb is perfectly suited for one of my family’s favorite dishes—chili con carne. I’ve had to improvise a bit on the spices. The chile powder found in Irish spice sections doesn’t taste right because it isn’t made with ancho chiles, but there is an excellent selection of European paprika powders. Hot Hungarian paprika tastes a lot like New Mexican red chile powder, so it’s perfect for chili. A dash of Spanish pimenton, the smoked paprika powder, adds an aroma that reminds me of barbecue.

As crazy as it seems, one of the tastiest things coming out of my Irish Tex-Mex kitchen is lamb chili. It’s really great topped with shredded Irish sheep cheese.